Comparison of Allied and German frontline rifle strength before and after the Hundred Days Offensive 1918 and arrival of additional American troops.

Rumours of an armistice passed through all the armies on the Western Front with remarkable speed, but they were not always greeted with relief and happiness. On the contrary, the US Marine Elton Mackin remembered that whenever talk of peace came, ‘You saw men take a deep, full breath at the thought of it. You watched them look away beyond the front and picture hope. You watched men curl their lips in bitter disbelief, remembering the promises of rest camps, winter quarters, and other things. You heard them curse disinterestedly at men who dared to dream, and call them fools.’ It was not uncommon for the British, who had long specialized in dry, graveyard humour, to dismiss the whole thing as a conspiracy to undermine their morale. They knew how dangerous it was to think too much of peace. When the men of A. J. Turner’s battalion heard that an armistice would probably be signed the following day, they received it, he wrote, ‘with the usual scepticism’; one man quipping that ‘of course’ it would happen, ‘and Lloyd George will be bringing each of us a nice hot steak and kidney pie’.

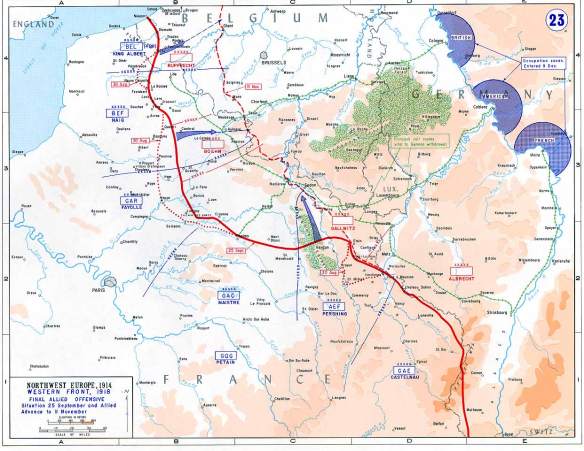

The increasing likelihood of peace, or at least some form of temporary ceasefire, weighed heavily upon Allied commanders. They knew that their armies, drawn from every corner of their societies, many of whom were wartime volunteers or conscripts, would only keep going for so long. The French had already mutinied in 1917 so there was little chance that Pétain could push them much harder, no matter how many times Foch pestered him. By the last weeks of the war the length of active front held by the French Army had narrowed dramatically in part owing to the convergent advances of the British and Americans on either wing, but also because it was rapidly running out of manpower. As for the BEF, it was, as Haig had told Lloyd George on 19 October, ‘never more efficient, but has fought hard, and it lacks reinforcements’. Even the Americans, who had no shortage of men, were beginning to tire. When Hunter Liggett took command of the US First Army in late October (Pershing having been elevated to the same authority as Haig and Pétain), he found, to his despair, that ‘some signs of discouragement were beginning to appear among both men and officers, the most conspicuous evidence of which was the great number of stragglers’, which he estimated to be as high as 100,000 men. Because American casualties had been so heavy, and because so many divisions were filled with raw recruits, a loss of cohesion and discipline was probably inevitable, but it was shocking nonetheless. There was only one thing to do: continue to push on and ensure that operations were conducted with as much care and attention to detail as possible.

Heavy fighting continued in the Franco-American sector in the south. By the last days of October, First Army had chewed its way through twenty-one kilometres of some of the worst ground on the Western Front, and had secured a good jump-off line for what Pershing hoped would be the final, decisive push. On 1 November, in conjunction with Gouraud’s forces on the left, three American corps launched a major offensive to secure the third German position on the Barricourt Heights. Once this had been achieved, the Americans would then be able to cross the Meuse and head up to the city of Sedan, severing the German rail links that supplied the rest of the front. The Americans may have tried to do too much too soon in earlier offensives, but they had learnt remarkably quickly, and the November offensive was noticeable for the care and attention to detail that preceded it. It was also helped by the disastrous state of the German defences. Along an eighteen-kilometre front there were barely seven divisions in the line, and they had long been worn out. There were a handful of reserve units, but they were unable to move up because of the shelling of the road network, and the collapse of the telephone system (also due to shelling) meant that their commanders were cut off. At Fifth Army headquarters, General von der Marwitz wanted to pull back behind the Meuse; a sensible and prudent manoeuvre that would have given his tired men a breathing space and allowed them to hold the river line. Instead OHL had forbidden any retirement because of its effect on the negotiations and compelled Marwitz to stand and fight where he was.

At 3.30 a.m. the preliminary shelling began, an agonizing two-hour ‘hurricane’ bombardment that pulverized the German defenders in their shell holes and trenches. Herbert L. McHenry, serving with 1st US Division, and in reserve that day, remembered watching the guns open fire – what he called ‘the real roaring sound of war’. ‘Then each of those “big babies” let go, it shook the earth, and as the “letting go” was continuous the earth was in a constant state of tremble.’ By noon the first lines of German prisoners were filing past their positions, the usual cowed young boys and stumbling old men. The Americans achieved remarkable success that day. Although some enemy regiments resisted stubbornly, most did not and US troops swept over the German lines, secured the high ground, and mauled whatever units they engaged. Hunter Liggett was mightily pleased with the results of the day’s fighting. ‘We had caught Von der Marwitz as I expected to – braced for the attack on his right. His weakened centre broke before the Fifth and Third Corps and these corps drove through to the Barricourt Ridge, as ordered, overrunning his entire defensive system …’

On the same day that Pershing’s corps had reached the Meuse, the Canadian Corps was in action on the outskirts of Valenciennes, attacking a fortified hill called Mont Houy that commanded the town. Furious attacks by British forces in the last days of October had come to nothing, so Arthur Currie had agreed to mount an operation to secure it. In what was a masterpiece of preparation and care, Currie’s gunners, led by the tireless Andrew McNaughton, went to work. ‘Owing to the fact that the German Army was approaching a defeat on a grand scale and that there was much peace talk in the air,’ a report on the operation stated, ‘it was decided that all restrictions concerning the economical use of supporting arms … were now out of place, and it was therefore the proper time to neglect economy.’ Six brigades of field artillery and 104 heavy guns, supported by nine batteries of heavy machine-guns (totalling seventy-two barrels), were brought up to the front. They were to launch a massive creeping barrage on the German positions at Zero Hour. Because of the layout of the ground, it was possible to deploy a great deal of artillery forward and allow a combination of not only frontal artillery fire, but also oblique, enfilade and, incredibly, reverse fire. It would not only be a startling demonstration of the effectiveness of Currie’s policy of ‘neglect nothing’, but a brutal illustration of the sheer weight and accuracy of firepower that the British and French Armies could wield in the closing months of the war.

On the cold, wet morning of 1 November, just one Canadian brigade, the 10th, went forward, supported by what historians have judged to be one of the most intensive fire plans of the war. During the attack seven tonnes of high explosive were fired every minute on a front of less than two miles, completely pulverizing the dazed defenders and tearing apart any defences they had made. If anywhere on the Western Front epitomized the Dante’s Inferno-like conditions faced by the German soldier in this period then it was Mont Houy. When Andrew McNaughton examined the cratered, smoking ground after the battle he noted that enemy dead were everywhere, ‘in rifle and machine gun pits, in trenches and sunken roads, in the open, in the rows of houses demolished by the siege howitzers; the concentrations, particularly those in enfilade on railway cuttings and other defiles, had left a shambles …’ In total the Germans had suffered 800 dead. Another 1,400 prisoners were being shepherded to the rear. The Canadians had suffered only 420 casualties, with just 60 fatalities, an astonishingly light figure given the strength of the enemy defences and the limited numbers of attackers. The German Army had no answer to this kind of punishment. Its soldiers, many still bravely led and well-trained, always took a toll on the attacking forces, but under such fire they could do little but retreat or die. If they decided to hold any position, they did so at a terrible risk and in the knowledge that it would only take a matter of days – sometimes hours – before the Allies pushed them off.

By the first week of November the German Army was in full retreat across the Western Front. From the air ‘we saw all the roads crowded with columns of men marching back,’ wrote one German pilot. Endless lines of weary troops splashed and shuffled their way eastwards, bowed down with their equipment, looking over their shoulders in fear, half expecting to see Allied aircraft or cavalry squadrons ready to scatter them again. It was an awful sight: the faces of young boys overshadowed by the steel helmets that were too big for them, or hobbling along in boots that had been worn away long ago; old veterans who had seen too many battles marching along with glassy eyes and a grim acceptance of death or wounding. It was by now a motley army; the exact opposite of the legions of proud feldgrau that had marched across Europe in the summer of 1914 on their way to enact Count von Schlieffen’s great war plan. The German Army had reached its end; worn down by four years of merciless slaughter and pounded into dust by the brutal Allied artillery bombardments. Some still believed in victory, in some divine intervention – a catastrophic outbreak of flu in Paris or London; a devastating fallout between the English and Americans perhaps – but most realized there was little they could do. How could they defeat the endless power of the Allied guns or their swarms of tanks? How many Americans would they have to kill before they too gave in? And in any case, was it really worth fighting and dying for any more? Did anyone really care whether Alsace-Lorraine was French or German?

Casualties were nothing short of catastrophic. Fritz von Lossberg estimated that by the time the German Army reached the Antwerp–Meuse Line it had lost over 400,000 men and 6,000 guns. Other authorities put it higher, and it is possible that between 18 July and 11 November the Army suffered 420,000 dead and wounded with another 385,000 men being taken prisoner. Such a magnitude of loss was simply unsustainable, and when this was combined with the thousands of casualties from Germany’s spring offensives earlier in the year – perhaps as high as a million – it meant that her army was bleeding to death. The strength of many units was now a fraction of their full establishments. According to Major-General von Kuhl, by the end of October most German battalions could muster only 450 men, and of them barely half were fighting troops, and this was almost certainly an overestimation. There were not enough men to man the trenches, not enough men to bring up the guns, and fewer and fewer reliable NCOs. For example, against the British Third Army, 111th Division registered company strengths of between fifty and sixty men. Likewise in 21st Reserve Division, one of its regiments was now down to three companies, each numbering around sixty soldiers, and this seems to have been entirely typical of the German Army in the West by this point, its ranks ravaged by the endless Allied attacks and stalked by the merciless influenza pandemic.

Given the chronic shortages of manpower, morale quickly declined. When rumours spread through units of the increasing rate of desertion, of how more and more men were simply giving up and heading for home, those at the front understandably asked why they should continue to suffer when others declined to do the same. Reinforcements would occasionally turn up, but they were always far fewer than had been promised and often surly and unhappy, always muttering about ‘war prolongers’ and doing nothing for unit cohesion. Adolf Hitler later complained that the arrival of recruits from home meant not a reinforcement but ‘a weakening of our fighting strength’, with the young ones being ‘mostly worthless’. Such was the toxic mixture of exhaustion and ill-discipline that was crippling the German Army. It was now nothing more than a collection of units, some good, mostly bad, but all lacking organization and structure. Commanders tried their best to explain to their men the importance of continuing to resist, but it was an almost hopeless task. Tales would be spread of the horrific consequences of peace with the Allies; of how the land would be exhausted and the people taxed beyond anything they had ever known. Second Army even issued a message to its troops in late October warning them that any peace would bring worse devastation to Germany than the struggle against Napoleon had in the last century. ‘Only when the enemy’s guns are silent forever is peace in sight,’ it read. ‘Until that happens we HAVE GOT TO FIGHT ON. Every man has got to do his duty, unless the enemy is to snatch victory at the eleventh hour. Only by setting our teeth and holding on to the end are we to get peace. THE FATHERLAND FOREVER.’

In spite of the increasingly shrill exhortations from its leaders, the Army gradually ceased to function. Orders would go missing; supporting artillery fire would never come; reports would not be written; supplies would never turn up. Alfred Mahncke, a staff officer with the German Air Force at Verviers, was tasked with organizing supplies to the front-line squadrons. ‘Considering the many shortages at this late stage of war,’ he wrote, ‘it was a thorny and almost hopeless task which could not be solved to everyone’s satisfaction.’ Lack of coal and strikes in the factories had a devastating effect on the number of engines, guns and ammunition he received, but getting enough fuel to the squadrons was his greatest challenge. By November, fighter squadrons were limping by on just 150 litres of aviation fuel a day – barely enough for a handful of individual sorties – which meant that the Air Force could no longer contest control of the skies. ‘I toiled at the centre of it all – compromising, balancing, reconciling and pacifying.’ The disintegration was noticeable even at OHL. Mahncke went to Spa for a meeting in early November and noticed that the atmosphere at the Hôtel Britannique was ‘tense and charged; nervous individuals rushed around, seemingly without purpose’.

Fritz von Lossberg was glad to leave Spa on 1 November. He had been shocked by the decline in efficiency and order. ‘Under Ludendorff there was a regime of strict discipline and deference,’ he wrote. ‘Now strong leadership was lacking. Now all the many self-important people were bragging. Everyone had his own opinion and liked to air it.’ As he was climbing into his car that morning, intending to travel to Strasbourg to take up his position as Chief of Staff to the Duke Albrecht of Württemberg (who commanded the southern sector of the German line in France), he was handed a telegram from the senior doctor of a military hospital in Antwerp. ‘Your son is ill with an infection in both lungs,’ it read. ‘His life is in grave danger.’ Lossberg’s son had already been wounded four times and had been employed as a desk officer at the Supreme Command until his fitness improved. Now, it seemed, his health had failed him again. Lossberg travelled on to Strasbourg, but as soon as he arrived he telephoned his wife and asked her to go to Antwerp. Unfortunately, by the time she reached Holland, mutiny had broken out and was spreading quickly behind the lines. ‘In order to return to Stuttgart she had to travel for five days in trains crammed with riotous soldiers,’ he remembered. ‘The transportation of our son from Antwerp ran into difficulties because the hospital trains were stormed and occupied by lawless people from behind the lines. It was not possible to evacuate the sick and wounded in an organised manner.’ Fortunately they managed to get on another hospital train that took them to safety in Germany.

By the last days of October the German Seventeenth, Second and Eighteenth Armies – those that had borne the brunt of British and French attacks since August – had occupied the line of the Sambre–Oise canal that ran from La Fère northeastwards up past Guise and Le Cateau. On 4 November the Allies would attack this line in what became one of the last great offensives on the Western Front: the Battle of the Sambre. Three British armies attacked along a twenty-mile front; pushing towards Avesnes and Mons, marching through difficult wooded terrain, hedgerows and orchards, and over numerous water obstacles ranging from canals and streams to irrigation ditches. To the south, the French were also on the move, extending the frontage of attack for another twenty miles, with Debeney’s First Army aiming for the town of La Capelle. Against them was an assorted collection of divisions from the battered Army Group of General von Boehn. The German positions were just hastily dug foxholes or rifle pits. There was not the time or the manpower to convert them into something more substantial, leaving the men in the open to face the oncoming storm. The history of 3rd Westphalian Regiment (holding the line at Raucourt near the Forest of Mormal) complained that:

The whole position consisted of rifle-pits connected up irregularly. There were no dug outs. There was no field of view owing to hedges, houses, walls and gardens. The battle headquarters were in small cellars, hardly splinter proof. In these inadequate positions weakened and used up troops awaited the attack of an overwhelming enemy.

The feelings of those soldiers can well be imagined as they crouched in the dirt under their steel helmets, clutching their rifles and breathing heavily through their foul-smelling rubber gas masks, waiting nervously for the bombardments to begin or the tanks to rumble forward.

Wilfred Owen would write what would turn out to be the final letter to his mother on 31 October, just after six in the evening. His battalion had moved up to the front several days earlier, taking up a position on the heavily wooded west bank of the Sambre canal, north of the village of Ors. Owen had been billeted in a stone cottage known as the ‘Forester’s House’. ‘So thick is the smoke in this cellar that I can hardly see by a candle 12 inches away, and so thick are the inmates that I can hardly write for pokes, nudges and jolts. On my left the Company Commander snores on a bench: other officers on wire beds behind me.’ Despite the discomfort, Owen seemed more content than he had been for many months. He ended by saying that he was perfectly safe and that ‘I hope you are as warm as I am; as serene in your room as I am here … you could not be visited by a band of friends half so fine as surround me here.’ Owen may not have said much about the forthcoming attack, but it must have weighed heavily on his men. All the bridges had been demolished by the retreating Germans, leaving the British with little option other than to swim the seventy-foot canal or improvise boats or bridges. On the far bank, the ground rose steadily away, giving enemy observers a clear view of the British lines. It was just like Bellenglise again, and many men shivered in apprehension at going over the top here, particularly when peace seemed so tantalizingly close.

The battalion attacked at 5.45 in the foggy, dew-stained morning of 4 November. Owen was in one of the assaulting companies. They went forward after a five-minute ‘hurricane’ bombardment fell on the far bank, before lifting 300 yards into the enemy defences, where it would remain for a further half an hour; more than enough time, staff officers had said, for the men to establish themselves across the canal, and push on eastwards. Unfortunately, as at Gouzeaucourt and at scattered places across the front throughout the Hundred Days, here the Germans were determined to stay put, and greeted the attackers with heavy machine-gun and rifle fire, pounding shells and mortar rounds that dug into the damp earth or splashed into the murky waters of the canal. The engineers and bridging specialists who had been called in to get the Manchesters over the obstacle could make little progress against such lethal fire. Thirty of the forty-two engineers tasked with putting pontoon bridges into place were killed or wounded, which left the battalion’s junior officers with no choice but to secure the bridges as best they could.

One of those who fought in this sector was Leutnant Erich Alenfeld, serving with 280th Field Artillery Regiment, whose batteries were dug in about 600 metres from the far bank. They were woken shortly before 6 a.m. when a heavy bombardment opened on their position. They immediately fired off flares to warn the other batteries and commenced firing ‘like the devil’. ‘The battle has broken out,’ he remembered. ‘We continuously shoot protective barrages in waves, that is, allowing the artillery to increase and decrease. The enemy is no less active. There are howls and crashes, a grey wall spreads out before us, and the enemy shrouds us in smoke. Machine gun fire can be heard from close by.’ News reached Alenfeld that the British were coming.

I know what this means; there’s a reason we are here. I fasten on my sling and pistol, bag and water, give my luggage to my batman and just want to give the new order, when I’m told that I should engage the enemy on the banks of the canal. I call Jacoby to my side, explain the situation to him, leave the third gun to him (on the left flank), say goodbye with a handshake and assume command of the right column, gunners at the ready! I tell them what is going on in a few words, and ask them to hold on with me until the end.

Alenfeld fought along the canal all morning, beating off attacks and organizing protective fire from his guns, before eventually being wounded. ‘I am the first to be hit in the left thigh and the right upper arm – I throw myself on the ground; next to me the brave telephone operator Herten falls to the ground screaming.’ Alenfeld could now see British troops about 300 metres from where he was lying, but fortunately one of his gunners dragged him back to the battery, where he was attended by a medical orderly. ‘The arm wound is nothing, a scrape on my skin, the leg is bleeding quite a bit.’ Alenfeld then had to make a decision, whether to hold on until reinforcements arrived or retreat. In the end, seeing that the main road to Landrecies was already in British hands he ordered his men to fall back.

The Manchesters suffered heavily that day. One of their most promising officers, Second-Lieutenant James Kirk, was killed operating a Lewis gun on the far bank of the canal, after having paddled a raft across under heavy fire. He kept up a constant fire, vainly attempting to suppress the incoming machine-gun rounds so that his men could survive. He would later be awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, his citation commending his ‘supreme contempt for danger and magnificent self-sacrifice’ that he showed that day. It was an awful scene: heavy machine-gun bullets scything through the dark waters and shredding the thin lines of infantry; artillery fire on the banks; smoke; confusion. His fellow officer, Wilfred Owen, was last seen on a raft in the water with some of his men when he came under murderous machine-gun fire. At one point he comforted two members of his platoon – green young boys – telling them ‘well done’ and ‘you’re doing well’, hoping to instil some courage into them, even as it became clear that the battalion would not be able to cross here. Shortly afterwards Owen was shot and killed. Thus, on 4 November, seven days before the Armistice, ended the life of the most promising English poet since Keats.

Despite the carnage at Ors, 4 November had been a day of good returns for the Allies with most divisions taking their objectives on time without running into heavy resistance. Rawlinson’s Fourth Army had crossed the Sambre–Oise canal across a fifteen-mile front and taken over 4,000 prisoners. To the south, Debeney’s French troops had also encountered ‘energetic resistance’ in getting over the canal – footbridges could not be secured and the troops had to raft themselves across – but they would march into the village of Guise the following day. For the Germans, however, it was the same dispiriting story of crushing bombardments, heavy attacks and panicked retreats. Leutnant Alenfeld and his men fell back at 2.30 p.m., marching away from the fighting with their wounded on stretchers, trying to escape the attention of passing aircraft. Although British shellfire continually harassed them, it was the aircraft that they really hated; flying low, shooting and throwing bombs and grenades at anything they saw. By the time darkness fell they were in Maroilles, four miles from the canal, getting their wounded treated while they snatched quick mugs of coffee. There were no horses or trucks available, so they spent the next six hours continuing the retreat, marching on dead feet towards Avesnes (‘countless columns march beside us’), which only two months before had housed the Advanced Headquarters of the Supreme Command. Alenfeld’s battery had lost two dead, seventeen wounded, five missing, and a number of guns and horses. When they reached their destination, they could rest for the time being and reflect upon what had happened. ‘Since the Englishman is cowardly,’ he raged, ‘he attacks only if he finds no opposition. His artillery shoots well. The airmen are too many for us to deal with. They have absolute control of the air, they simply go for a flight and do a lot of damage … Germany is defeated and the conditions of peace are dreadful. With Austria’s collapse everything becomes much worse still …’

A question was on everyone’s lips: how long could this go on?