By late September 1915 the stalemate of trench warfare at last appeared to be gripping the Eastern Front, and the world’s attention returned to the dreary struggle of the Western Front, the debacle at Gallipoli, and the destruction of Serbia. The tsar’s armies now rested and were rebuilt with better logistics while he and his son toured the front to raise morale. In the Caucasus, the world had been shocked by the Turkish massacre of Armenians in spring 1915. By July this had permitted a Russian advance to Van, but that city was soon again abandoned. In December, however, Yudenich opened a major offensive in Armenia which led to the storming on 16 February 1916 of the strategic fortress of Ezerum after three days of bitter fighting. The Turks continued to retreat and by 21 February 1916 General D. K. Abatsiev’s forces had taken the major strongpoint of Bitlis, and in July Erzingan. In the meantime Liakhov’s Coastal Detachment, well supported by the Black Sea Fleet, had advanced down the Caucasian coast and on 4-5 April, he seized the major Ottoman supply port of Trebizond.

The tsar’s forces also entered Ottoman Persia in fall 1915 in order to divert the Turks by linking up with the British. This advance passed through Kasvin, Hamadan, and on 13 February 1916, Kirmanshah. The Russians then turned westward to threaten the Turkish flank in Mesopotamia and help relieve the besieged British force at Kut. Their march continued after the fall of Kut (16 April) to Khanikin and Rowanduz while another detachment joined the British on the Tigris. These successes compared favorably with the Allied failure at the Dardanelies and a secret Anglo-Franco-Russian treaty carving up Asiatic Turkey therefore awarded Russia Armenia, part of Kurdistan, and all of northern Anatolia. This pact supplemented the March 1915 promise that Russia would receive Constantinople and the Straits, and it demonstrates the importance still accorded Russia by Allied statesmen. Inter-allied cooperation was further strengthened by the dispatch of a Russian brigade to the Western Front while on 15 July 1916 another joined the Allies at Salonika. And in spite of Turkish recovery of Khanikin, Kirmanshah, Hamadan, Musg, and Bitlis, the Russians ended 1916 confident of future success in both Persia and the Caucasus. Moreover, Admiral A. V Kolchak, the new commander-in-chief of the Black Sea Fleet, had initiated an aggressive mining policy that had blocked the Bosphorus and returned control of that sea to the Russians.

Signs of improvement appeared elsewhere as well. On 23-25 November 1915 Stavka’s representatives in France met the Allies near Chantilly to coordinate plans for 1916 plans, and in December 1915 the Eleventh Corps on the Russian European Front launched a limited local offensive along the River Strypa. If the latter failed to break through enemy trenches and had no effect upon German planning, it was a sign that the Russian Army was far from destroyed. Nonetheless, on 8 February 1916 General von Falkenhayn opened the German campaign to destroy the French on the anvil of Verdun, while the Austrians now focused on routing the Italians in the Trentino.

By March 1916 the Russians were sufficiently recovered to respond to a French appeal with a major, two-pronged assault on the German entrenchments at Lake Naroch and Visjnevskoe, south of Dvinsk. In spite of a two-day bombardment, this 1915-style attack failed utterly. Whatever relief it gave the French at Verdun, the cost was perhaps 110,000 Russian casualties to 20,000 Germans, and it showed clearly that conditions on the Eastern Front paralleled fully the trench war in the West. Most generals now assumed that preliminary bombardments, followed by massive infantry assaults to produce breakthroughs to be exploited by cavalry, were the solution to the stalemate the Russians called “position warfare.” When these tactics failed, the generals again blamed shortages of munitions. So for a new offensive in the Vilnius area, the local command had demanded even more guns and shells. But these concentrations had precluded surprise at Naroch, and the bombardment on a very narrow front merely turned the battlefield into a muddy morass on which defensive firepower allowed even inferior forces of defenders to inflict stupendous losses upon the attackers.

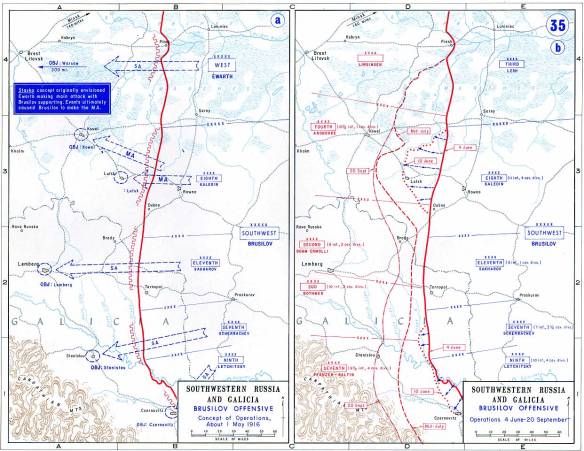

Fortunately for the Russians, the generals gathered around Brusilov, now commanding the Southwestern Front, had pondered recent failures and developed new sets of operational and tactical approaches. These envisaged employing infantry assaults simultaneously at several different places with a minimum of artillery preparation. In fact, since Stavka was supporting the offensives in the north, when Brusilov proposed launching a secondary offensive, he was forced to achieve surprise by using only the forces in place for his planned strike toward the Carpathians. This was to take place along a 14-mile front at Lutsk, supported by attacks on smaller sectors at Tarnopol and Yazlovetsa, and a demonstration toward Lvov. Aerial photographs were used to brief his troops on opposing trench systems while secrecy was preserved by effective camouflage and building large underground bunkers, in which to hide the attackers. He also dispensed with the always visible cavalry, usually concentrated in masses behind the front, at the risk of not being able to support a breakthrough.

In the meantime the ltalians had appealed for help after the Austrians overran their positions in the Trentino. Consequendy, Brusilov launched his offensive 11 days early, on 22 May 1916. His armies struck along a 300-mile front in Galicia and Bukovina, with the important rail center at Kovel as their target. Because Stavka had withheld artillery support, Brusilov’s own guns fired only 250 rounds each in the first two days as compared to 600 rounds used daily on the Somme. Surprise was complete and the Austrian lines were ruptured, Lutsk recaptured, and the battle joined along the Strypa River (29 May-17 June). The Hapsburg forces were completely disorganized and demoralized, forcing the Germans once more to come to their aid. Making efficient use of the rail net, the Germans attacked the northern edge of the Lutsk salient. This stabilized the front, but not before Chernowitz fell to Brusilov’s Russians. Meanwhile, to the north, Stavka had attacked from Baranovichi. But like the simultaneous Battle of the Somme in France, this assault failed to break the opposing line, although the fighting lasted only 12 days. As for Brusilov, he now reverted to employing heavy bombardments and massive infantry attacks that failed to take the Kovno railhead. He declared his offensive ended on 31 July, though some heavy fighting continued thereafter, and his forces suffered 500,000 casualties in all. Yet his opponents had lost 1.5 million men and 582 guns.

Unfortunately Brusilov’s successes were quickly balanced by defeats elsewhere. After prolonged negotiations, Allied promises and Russia’s Galician victories persuaded the Rumanians to enter the war on 14 August 1916. Against Russian advice, they at once attacked Hungarian Transylvania, where Germans and Bulgarians under von Mackensen and von Falkenhayn quickly surrounded their forces at Hermannstadt. Having then captured the port of Constanza, the two German-Ied forces broke through the Carpathian passes into Wallachia and advanced upon Bucharest, which the Rumanians abandoned. As a result, Brusilov was soon forced to thin and extend his front some 300 miles to the southeast to open his own Rumanian front. The Rumanian retreat finally ended on the Sereth River in January 1917, but it left the Germans in control of Rumanian wheat and oil.

Despite this setback, the Allied meeting at Chantilly in November 1916 remained optimistic due to the German failure at Verdun and Brusilov’s success in the East. Although Alekseev was concerned over the Balkans, the Allies put that region in second place in their plans for victory in 1917. Nicholas 11 shared this view and Stavka began implementing the Chantilly plan for simultaneous offensives in France, Italy, and Russia. To keep the Germans off balance, in late December Russia’s Northern Front struck silendy through the fog to open the Mitau Operation, which recaptured and held Riga in a five-day batde. But on 9 January 1917 the Germans counterattacked and in time recovered most of the lost ground. Nevertheless, by the month’s end the 12th Army had stopped the Germans and held before Riga. The Mitau Operation, the last offensive of the tsar’s Stavka, demonstrated that Brusilov’s methods had spread throughout the Imperial Army, that it was still capable of defeating both Austrians and Germans, and that it could cooperate in the Allies’ planned offensives.

That this was possible was thanks to the industrial mobilization carried out under the aegis of the Special Council for State Defense. Since 1914 the Russian economy had expanded, not collapsed, with growth rates over 110 percent annually. The tsar wisely resisted Stavka’s proposal of mid-1916 for a military dictatorship. By 1917 the output of rifles was up 1,100 percent, that of shells by 2,000 percent, and in October 1917 the victorious Bolsheviks inherited a reserve of 18 million shells. The story was similar in other areas of production and by January 1917 Russian soldiers finally were entering battle fully equipped with even reserve gasmasks. What gaps remained promised to be filled by Allied aid after the Inter-Allied conference that opened in Petrograd on 19 January 1917. Manpower demands had slackened with only 3,048,000 men having been added in 1916. But if this gave a grand total of 14,648,000 since August 1914, most of these new troops were of declining quality, and war-weariness was sapping civilian morale. Most important, in June 1916 an order to draft 400,000 inhabitants from Turkestan and Central Asia provoked a major rebellion that sucked off forces to put it down.

At the same time, rapid industrialization had brought urban overcrowding, wartime shortages, and inflation. The value of the paper ruble, which increased in circulation six times as compared to 1914, had dropped from 56 to 27 kopecks by 1917. Most significant of all was the crisis provoked by the overloaded and aging railway system. The tsar and his ministers sought fixes that would prevent breakdowns, food shortages, and riots. Yet Nicholas’ attempt to have the new chairman of the Council of Ministers, Prince M. D. Golytsyn, reorganize the transport system failed, and this led directly to the food riots in Petrograd that sparked the revolution and forestalled the regime’s remedial measures.

If Russia’s leaders still had room for optimism in January 1917, their efforts were being undercut by the pessimism reigning in unofficial Russian political circles. This last was a major factor in the February Revolution. It stemmed from a general war-weariness, but also from the persistent “antiblack forces” campaign. This last had made it difficult for the monarch to find acceptable ministers even since the reconvening of the Duma in February 1916. Though Nicholas apparently ignored his wife’s advice, Rasputin’s claims of influence gave credence to mounting rumors. Then in October, the Progressive Bloc’s bureau resolved to attack the government in the person of Chairman of the Council of Ministers R. V. Sturmer, whom they saw as a German protege of Rasputin. When the Duma reassembled in November 1916, both the Kadet leader P. N. Miliukov on the Left, and V. V. Shulgin and V. A. Malakov on the Right, delivered seditious speeches accusing the government of conduct that was either stupid or treasonous. Rumors of a separate peace increased, and this despite formal denials by the ministers for war and the navy. Nicholas’ changes of other ministers brought little relief and, faced with further opposition demands, the tsar stood firm.

On the night before the Duma adjourned in late 1916, highly placed conspirators assassinated Rasputin. But this achieved nothing and, by early 1917, Imperial Russia presented a strange picture. Its successful industrial mobilization and recent military achievements had little impact on the pessimism in the rear. Even as Nicholas struggled with the railway and provisioning crisis, the French and British ambassadors overstepped diplomatic bounds and advised him to make concessions. Rumors were rife that the tsar was under pressure to abdicate, and that plans were afoot for a palace military coup d’etat. Even Grand Duke Nikolai failed to tell the tsar that the mayor of Tiflis had proposed that he lead an anti-tsarist coup, but that he had refused on the grounds that the army would not follow him. Thus the Empire entered a new period of winter shortages as a house divided against itself.