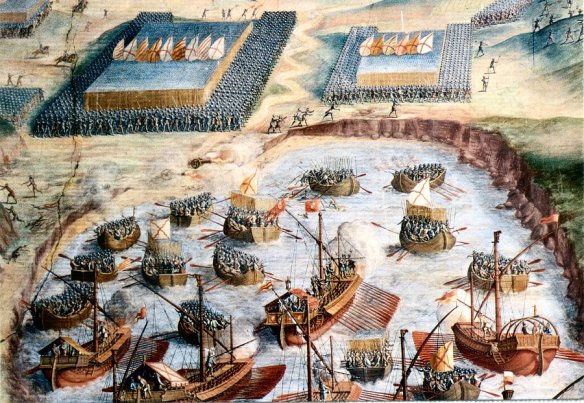

Disembarkation of the Spanish tercios in the Terceiras islands (26 july 1583) (detail). Fresco by Niccolò Granello, Sala de las Batallas, Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid, Spain.

THE STRUGGLE FOR THE AZORES, 1582-3 The map on the right highlights the strategic importance of the Azores as a stopping-over point and provisioning base for returning Spanish treasure fleets and Portuguese spice carracks. In hostile hands, the Azores would not only have deprived the Spanish and Portuguese of a vital place of refuge, but would have been perfect bases for corsairs. The routes of outbound Spanish and Portuguese vessels were further south to take advantage of prevailing winds and current patterns.

Although it might easily have been otherwise, the Ottoman-Habsburg struggle for Mediterranean dominance now trailed off into stalemate. Uluj Ali Pasha’s capture of Tunis and La Goletta in 1574, although operationally brilliant, yielded modest strategic dividends. For its part, Spain commanded inadequate resources for major offensive action, but, in the absence of a significant threat, adopted an aggressive posture. Alvaro de Bazan’s galleys ravaged the North African coast with impunity in 1576, showing that war could still cost the Turks. But as the threat diminished in the Mediterranean, Spain’s difficulties in the Netherlands grew apace. At the same time, the Ottomans nervously eyed their eastern frontier, where 1577 began a thirteen-year war with the Safavids. That same year, Sultan Murad III concluded an armistice with Philip of Spain that would be periodically renewed until the negotiation of a definitive peace in 1587.

But Spain was not the only Catholic nation with crusading impulses and Mediterranean ambitions, and in 1578 the young Portuguese king, Sebastian, led an army into Morocco to overthrow the sharif, an Ottoman surrogate, and install his own client. The Moroccans were as well supplied with gunpowder weapons as the Portuguese and as skilled in their use, and won a crushing victory on 4 August at Alcazarquivir. Sebastian died in the battle, and his entire army, including the cream of the Portuguese nobility, was killed or captured. The Portuguese throne fell by default to Cardinal Henry, ageing and in ill health, the last legitimate descendant of the Avis line. These developments were noted with alacrity by Philip of Spain, who had a solid claim to the throne through his mother, a Portuguese princess. Henry died in February 1580, having spent much of Portugal’s treasure to ransom (idalgas, members of the nobility captured at Alcazarquivir. Philip had used the intervening years to good advantage, discreetly negotiating his terms of succession with Henry, arriving at an arrangement that preserved Portugal’s empire and governmental institutions and secured the acquiescence of the nobility and wealthy merchants.

There was, however, considerable anti-Spanish sentiment among the ordinary Portuguese, and Sebastian’s illegitimate cousin, Dom Antonio, a wealthy friar, proclaimed himself king with considerable popular support. Philip responded by invading Portugal and dispatching envoys to Portugal’s imperial possessions to press his case. The invasion had two arms: an army driving on Lisbon from the east through Estremadura, and a smaller force working its way along the southern coast with naval support. Philip again displayed his skill at selecting subordinates, assigning the main force to the Duke of Alba, ageing but still widely respected; the southern army to the Duke of Medina Sidonia; and naval command to Bazan, getting on in years but thoroughly competent. It was Philip’s finest hour as commander-in-chief. Henry’s expenditure for ransoms had left little for defence; the Spanish moved swiftly and, in Alba’s case, with remarkable restraint. The Spanish forces united and, after a short, stiff fight – Alba’s last battle, and perhaps his best – Lisbon surrendered on 18 July 1580. Dom Antonio fled north and on 23 October left the country aboard an English ship.

Philip’s lieutenants had left Portuguese governance intact, and internal resistance evaporated. The Indies and Brazil accepted Spanish rule, the latter with some enthusiasm in the light of French designs on its trade. Of the Portuguese empire, only the Azores, excepting the island of Sao Miguel, held for Dom Antonio, a matter that quickly aroused interest in London and, of greater import, Paris. That interest was heightened when a small Spanish expedition that had been sent in 1581 to reclaim the islands was repulsed. This was a serious matter, for the Azores were vital to the operation of convoys from both the East and West Indies; the Flota de Tierra Firme, Flota de Nueva Espana and Carriera das Indias, the treasure and spice convoys, used them for watering and provisioning on their way home and as a rendezvous point for their escorts. They were a perfect base from which to prey on Habsburg commerce.

Sensing opportunity, Catherine de Medici, dowager queen of France, resolved to support Dom Antonio’s claim and, in the spring of 1582, dispatched an expeditionary force under Philip Strozzi of some 60 ships, half of them large, carrying 6-7,000 soldiers, the largest French maritime expedition until the age of Louis XIV: Sailing with the implicit blessing of Queen Elizabeth, it included several English ships. Alive to the danger, Philip dispatched a fleet under Bazan. Consisting of 2 large Portuguese warships, 19 armed merchantmen and 10 transports carrying 4,500 soldiers, it met Strozzi’s force on 24 July 1582. After an indecisive encounter, the two fleets met two days later, some 18 miles south of Sao Miguel, in a fierce engagement named after the island’s capital, Punta Delgada. The French initially had the advantage of the wind and attacked the Spanish rear with superior forces, but Bazan doubled with his van, precipitating a melee. Although the French enjoyed advantages in terms of weatherliness and, initially, in order, the Spanish prevailed by sheer hard fighting. The galleon San Mateo, the focal point of the battle, was assailed by no less than seven French ships, including Strozzi’s Capitana (flagship), in an action that ultimately drew in Bazan’s Capitana. While the major warships on both sides were amply provided with cannon, it was a battle of boarding and counterboarding that was decided by small arms, edged weapons and valour. The French lost ten ships, including Strozzi’s flagship, which was boarded and captured. Strozzi himself took a Spanish arquebus ball and died a captive aboard Bazan’s Capitana.

Punta Delgada was the first major naval engagement fought far from any continental landmass and would be the last until the battle of Midway in 1942. Although modern historians have largely ignored Punta Delgada, the English sea dog Sir William Monson was quite right to cite its importance. Although French adventurers and Dom Antonio’s partisans still held the Azores, save for Sao Miguel, Punta Delgada was decisive. Bazan returned the next year with a massive armada: 5 galleons, 2 galleasses and 12 galleys, together with 79 sailing ships, 30 large and the rest small, carrying some 15,372 soldiers. Uniting his fleet at Sao Miguel on 19 July 1582 – the galleys sailed independently, arriving eleven days ahead of the rest – Bazan directed his force at Terceira, the largest of the Azores in French hands. After a careful reconnaissance, he selected the least heavily defended of three feasible beaches and mounted a model amphibious invasion, the galleys providing fire support for infantry carried ashore in small craft. Bazan’s account of the action has a strikingly modern tone:

… receiving many cannonades … the [flag] galley began to batter and dismount the enemy artillery and the rest of the galleys [did likewise] … and the landing boats ran aground and placed the soldiers at the sides of the forts, and along the trenches, although with much difficulty and working under the pressure of the furious artillery, arquebus, and musket fire of the enemy. And the soldiers mounting [the trenches] in several places came under heavy arquebus and musket fire, but finally won the forts and trenches.

With Spanish infantry ashore in superior numbers resistance on Terceira collapsed, the other islands following suit. Dom Antonio got off with his skin and little else. The Azores held for Spain, and the Indies convoys continued unhindered. Flushed with victory, Bazan advised his imperial master that England could be invaded by sea. Thus stimulated, Philip asked his commander in Flanders, Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, about the feasibility of such a project. Parma was unenthusiastic, preferring a surprise attack across the Channel to Bazan’s proposal to invade from Iberia; Parma did not, however, rule it out.