The orders did not reveal either the strength of Lee’s army—McClellan’s cavalry commander had put the number at an unrealistic 120,000—or whether the Confederates had followed the routes specified by Lee. Consequently, McClellan spent the afternoon seeking further corroboration of the order’s details. He directed Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton, the cavalry commander, “to ascertain whether this order of march has thus far been followed by the enemy.” The sound of gunfire from Harper’s Ferry indicated that the garrison had not surrendered. It was in the early evening when Pleasonton reported that the evidence indicated that the enemy had complied with Lee’s orders.

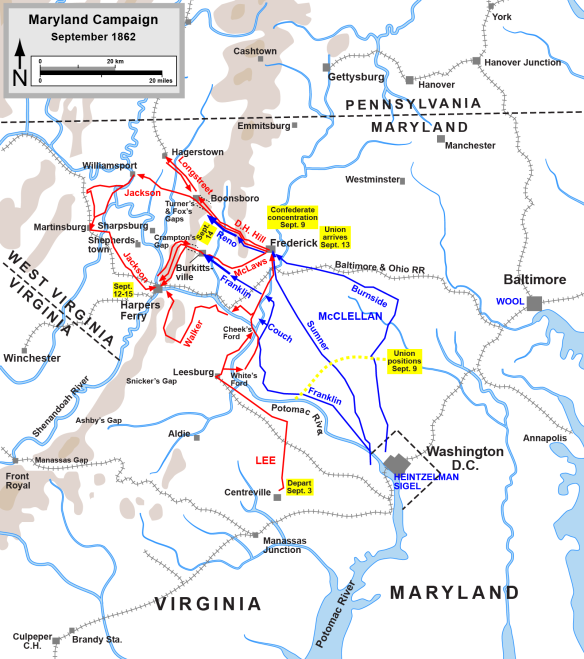

To relieve the troops at Harper’s Ferry, McClellan decided to advance on Turner’s Gap, Boonsborough, and Crampton’s Gap, eight miles south of Turner’s Gap. Eighteen hours passed, however, from the time McClellan was handed the copy of Lee’s order until his units marched on the morning of September 14. His efforts to obtain additional intelligence on the afternoon of September 13 were reasonable, but the situation clamored for aggressiveness. He should have, with minimal risk, pushed his infantry columns closer to the gaps. At no time, however, could McClellan have struck a contingent of the Confederate army unless Lee chose to stand and give battle. Although fortune had given McClellan the strategic initiative, Lee could still dictate whether there would be an engagement at a time and place of his choosing.

It was past nightfall when a courier delivered a message from Jeb Stuart to Lee at Hagerstown. Hours before, a Southern sympathizer had found Stuart at the eastern base of South Mountain. Stuart’s cavalrymen had been skirmishing with their mounted opponents in the valley around Middletown since early morning. Approaching Stuart, the Marylander related that he had been standing outside of McClellan’s tent when the Union general read a document and exclaimed that he now knew what to do. It remains uncertain whether Stuart surmised that McClellan possessed a copy of Special Orders No. 191. Although his message to Lee has not been found, Stuart apparently concluded that the Federal commander had learned that Lee had divided his army and that the enemy was moving to the relief of the Harper’s Ferry garrison.

Shortly after Lee received Stuart’s dispatch a message arrived from Harvey Hill at Boonsborough, reporting that the entire Federal army appeared to be bivouacked on the valley floor east of Turner’s Gap. Lee had spent the day waiting anxiously on news from either Jackson or McLaws on the seizure of Harper’s Ferry. Now the threat to his dispersed army was critical. Lee admitted later that McClellan’s change in tactics had surprised him.

Lee summoned Longstreet to the headquarters tent, gave him the messages from Stuart and Hill, and then stated that they would defend the South Mountain gaps. He wanted Longstreet to march at daylight with his two infantry divisions and artillery to Boonsborough, thirteen miles to the south. Longstreet disagreed, arguing that his command and Hill’s should withdraw to Sharpsburg, where they could threaten the flank and rear of the Federals as they marched down Pleasant Valley toward Harper’s Ferry. Lee “would not agree,” said Longstreet, and ordered the advance. Returning to his tent Longstreet put his argument in writing and sent the note to army headquarters. Lee did not reply.

Sometime after midnight on September 14 a second message from Stuart arrived at army headquarters. In it (the dispatch is missing) Stuart either implied or stated positively that McClellan had obtained a copy of Special Orders No. 191. The dispatch confirmed for Lee why his opponent was acting with unaccustomed aggressiveness. Whether or not McClellan possessed a copy of the orders, the campaign turned against the Confederates when the Union army reached Frederick. Lee could not abandon the campaign and retreat into Virginia, as he believed he had come too far to do so. He was thus left with one choice: buy time for the completion of the Harper’s Ferry operations and the reuniting of his army by slowing the Federal passage through South Mountain.

Lee’s instructions to Stuart and Hill were unequivocal: “The gap must be held at all hazards until the operations at Harper’s Ferry are finished. You must keep me informed of the strength of the enemy’s forces moving up by either.” Although “the gap” was unspecified, Lee meant Turner’s Gap, where he expected Stuart and Hill to conduct its defense. The cavalry commander was convinced, however, that the main Federal thrust would be at Crampton’s Gap and the road into Pleasant Valley in the rear of McLaws’s and Anderson’s troops. Soon after daylight on September 14, Stuart rode south toward the mountain defile, apparently without notifying Hill. The defense of Turner’s Gap and Fox’s Gap, a mile to the south, fell to Harvey Hill, of whom Porter Alexander said, “There is not living a more honest fighter.”

Hill rode to the crest of South Mountain before sunrise on September 14. Colonel Alfred H. Colquitt’s brigade of Georgians and Alabamians had spent the previous day and night on the mountain at Turner’s Gap. Hill ordered them down the eastern face to the mountain’s base and into line. Before long Brigadier General Samuel Garland Jr.’s North Carolinians arrived and were deployed at Fox’s Gap. Hill’s other three brigades were miles to the rear. In all, Hill commanded fewer than 5,000 officers and men.

A North Carolinian wrote of Hill, “The clash of battle was not a confusing din to him, but an exciting scene that awakened his spirit and his genius.” One of his veterans observed in a postwar letter to the general, “If you had a fault as a division-commander, it seems to us to have been the fortunate one of excess of determination and pugnacity in the face of appalling difficulties and danger.” The former soldier did not specify a particular engagement, but this day on South Mountain fit the description.

Union Ninth Corps troops advanced on Fox’s Gap at about nine o’clock, clashing with the 5th Virginia Cavalry and a battery of horse artillery, left behind by Stuart, and Garland’s North Carolinians. South Mountain rose 1,300 feet in elevation, and its scarred face, with wooded hollows and knolls, thick underbrush, and entangled patches of mountain laurel, aided the defenders. But the Federals kept pushing back the beleaguered Rebels. While standing with the 13th North Carolina on the front line, Garland was struck and killed. Hill described the brigadier in his report as “the most fearless man I ever knew.” The attackers scattered the North Carolinians and reached the crest, where the Old Sharpsburg Road passed through the gap.

Fortune intervened for Hill. The Union attack stalled on the crest before the fire of the horse artillery and a pair of cannon sent in by Hill. A patchwork force of Rebels supported the guns. Amid the smoke and tangled underbrush the Federal officers, believing they had encountered another battleline, asked for reinforcements. To the north, at Turner’s Gap, Colquitt’s men awaited a slowly developing assault by the Union First Corps.

With Garland’s ranks broken and Colquitt’s line facing an overwhelming enemy force, Hill ordered forward his three brigades from Boonsborough. Brigadier General George B. Anderson’s North Carolinians arrived first and were shifted to the right. Behind them the Alabama regiments of Brigadier General Robert E. Rodes moved over the crest in support of the left flank of Colquitt’s troops, who were now engaged in a fierce struggle along National Road. When Brigadier General Roswell Ripley’s brigade came up, Hill directed it toward Anderson’s command. In Hill’s words, he had “played the game of bluff” until these units reached him.

After a grueling march from Hagerstown in which hundreds of men fell exhausted in the heat and dust, the two leading brigades of Longstreet’s divisions arrived at Turner’s Gap at midafternoon. Hill sent them toward Fox’s Gap and assigned Ripley to overall command of the action. The fighting there dissolved into a bungling, confusing affair. The Yankees renewed their attacks, piercing a gap in the Confederate ranks and driving them rearward. Ripley’s brigade became disoriented in the wooded terrain and angled away from the combat. Hill declared to Longstreet in a postwar letter that Ripley “was a coward and did nothing.” A Georgia colonel stated, “Ripley gave himself but little concern about what was going on.”

The situation at Fox’s Gap stabilized at last with the appearance of John Hood and his redoubtable fighters. Hood had been placed under arrest by Longstreet in a dispute with Shanks Evans over captured ambulances at Second Manassas. When Hood’s men reached the western foot of South Mountain, they saw Lee, who had preceded the troops in an ambulance, and shouted to the commanding general, “Give us Hood!” In response Lee temporarily suspended the brigadier’s arrest. When the Texans heard the news, they yelled, “Hurrah for General Lee! Hurrah for General Hood! Go to hell, Evans!”

Hood’s presence on the crest solidified the Confederate right flank. To the north, at Turner’s Gap, Colquitt’s and Rodes’s veterans clung to the ground against mounting odds. The fighting lengthened into the night, the opposing lines marked by musket flashes. A Yankee attested that the “sides of the mountain seemed in a blaze of flame.” The enveloping darkness ended the clash. Longstreet had joined Hill on the crest and informed Lee that he could not hold the position another day without reinforcements. Lee had none and ordered a withdrawal. According to Moxley Sorrel, it was “a bad night” on the mountain as the Rebels filed down the western face, leaving behind their dead and wounded. Confederate cavalry formed a rear guard and remained on the mountaintop.

The defense of Turner’s Gap and Fox’s Gap had cost the Confederates 1,950 in killed, wounded, and captured; the Federals, about 1,800. In his report Hill praised his troops’ stand “as one of the most remarkable and creditable of the war.” He deserved blame, however, for not sooner ordering forward the brigades of Anderson, Rodes, and Ripley. The Federals’ hesitation to press the advance on the crest at Fox’s Gap and their slowly developing attack at Turner’s Gap spared Hill from a likely defeat. The stubborn fighting by Colquitt’s and Rodes’s men and the timely arrival of Longstreet’s troops salvaged the day for the Confederates.

Longstreet, Hill, and Hood rode off the mountain ahead of the troops and met with Lee. Almost certainly they discussed the condition of the officers and men and the likely enemy movement across South Mountain in the morning. “After a long debate,” in Hood’s words, Lee decided that the retreat should proceed through Sharpsburg to the Potomac River and into Virginia, the campaign in Maryland would be abandoned. After the meeting Lee sent messages written by Robert Chilton to Jackson and McLaws, dated 8:00 P.M., September 14. In them Lee directed Jackson to withdraw from Harper’s Ferry and to proceed to Shepherdstown, where he could cover the retreat of the units with Lee across the Potomac. The dispatch to McLaws read: “The day has gone against us and this army will go by Sharpsburg and cross the river. It is necessary for you to abandon your position to-night.”

Two hours later Lee learned of the Federal’s seizure of Crampton’s Gap and their advance into Pleasant Valley. As noted, Jeb Stuart rode to the defile, where he had sent Wade Hampton’s cavalry brigade on September 13. On that day the gap had been manned by Colonel Thomas Munford with 400 troopers, 300 infantrymen, and six cannon. When Stuart arrived, he learned “that the enemy had made no demonstration toward Crampton’s Gap up to that time.” The inactivity by the Federals persuaded him that they were marching directly along the Potomac River, bypassing South Mountain, to Harper’s Ferry. He dispatched Hampton’s 1,200 horsemen to cover the roads along the river and instructed Munford to “hold it [the gap] against the enemy at all hazards.” Once again Stuart had misjudged the Yankees’ intentions. Leaving the defense of Crampton’s Gap to Munford’s small force, he rode on to Maryland Heights.

The Federals were marching, however, to Crampton’s Gap. They did not reach Burkittsville, east of the gap, until after midday. McClellan had instructed Major General William B. Franklin, Sixth Corps and acting wing commander, “to attack the enemy in detail & beat him.” McClellan expected Franklin to act energetically; instead he halted the march in violation of orders until a trailing division joined his corps. When they appeared before the gap, one of Munford’s men noted: “As they drew nearer, the whole country seemed to be full of bluecoats. They were so numerous that it looked as if they were creeping up out of the ground.” Only a few hours of daylight remained when Franklin’s infantrymen attacked.

For two hours the Confederates valiantly resisted the enemy assaults. Munford described the fighting as “the heaviest I ever engaged in, and the cavalry fought here with pistols and rifles.” When McLaws heard the sounds of battle, he sent Brigadier General Howell Cobb’s brigade to Munford. Cobb’s Georgians and North Carolinians arrived in time to be swept to the rear with Munford’s broken ranks. McLaws and Stuart rode toward the gap and tried to rally the men. Darkness prevented a Union pursuit, giving McLaws time to patch together a defensive line across Pleasant Valley. McLaws did not like Stuart personally, and he remarked to the cavalry commander, “Well General, we are in a pen, how am I to get out of it?”

The news from Crampton’s Gap temporarily altered Lee’s plans. Instead of Longstreet’s and Hill’s divisions, one-third of the army, marching through Sharpsburg to the Potomac, now they would halt at Keedysville, a small village three miles southwest of Boonsborough on the road to Sharpsburg. From there they could move against the enemy flank if the Federals crossed South Mountain and turned south toward McLaws’s and Anderson’s position on Maryland Heights. The security of those two divisions was foremost in Lee’s plans.

The withdrawal from Boonsborough began minutes past midnight on September 15. The bone-weary Confederates stumbled through the morning’s darkness. Overcome with exhaustion, uncounted numbers lay down in the fields and slept. Some managed to rejoin their comrades; others were captured hours later by the trailing Yankees. While en route Lee received a dispatch, dated 8:15 P.M., September 14, from Jackson, who wrote that he expected “complete success to-morrow.” With the morning’s light Lee saw that the terrain around Keedysville provided no good, natural defensive position. He ordered the column on to Sharpsburg.

As the Southerners crossed Antietam Creek, less than a mile east of Sharpsburg, they filed to the north and south, deploying into line on a string of ridges and hills. When Lee in his ambulance passed a group of soldiers, he reportedly said to them, “We will make our stand on those hills.” He stated in his report that the halt and deployment on the western side of Antietam Creek “reanimated the courage of the troops.” A staff officer said likewise, noting in his diary on this day, “Men in a grand humor for a fight.”