As a result of the differences in attitude, policy and design which existed prior to it, when the Second World War broke out in September 1939 the tanks of the various armies differed considerably in their characteristics and in their intended method of employment. In consequence, when they were put to test their performance varied a great deal.

So far as British tanks were concerned, the 40mm guns of the early cruiser tanks, from the Mark I to the Mark VI Crusader, and of the Matilda infantry tank, were superior in terms of armour penetration to the 37mm gun of the original Pz. Kpfw. III and almost equal to its short 50mm gun.

However, no attempt was made in Britain to develop a tank with a larger calibre dual-purpose gun like that of the Pz. Kpfw. IV. What was developed were only close support versions of the cruiser and infantry tanks armed with 76.2mm howitzers, which were limited-purpose weapons with no armour piercing capability and which were in no way comparable to the dual-purpose guns of similar calibre mounted at the time in Soviet as well as German tanks.

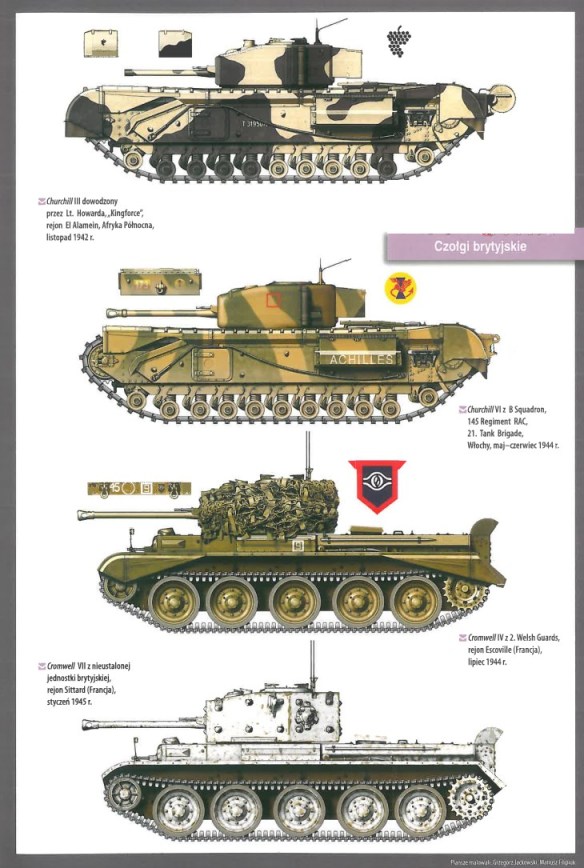

A larger, 57mm gun was mounted in 1942 in the Crusader III cruiser tank and Churchill III and IV infantry tanks. Its armour-piercing capabilities were considerably greater than those of the 40mm gun and almost the same as those of the long 75mm with which Pz. Kpfw. IV had been rearmed by then. But it was still inferior to the latter, and other 75 or 76mm guns, so far as high explosive shells were concerned. Moreover, there was no British tank with a more powerful gun that could match the 88mm gun of the Tiger, which had appeared in 1942.

In fact, cruiser and infantry tanks continued to have exactly the same main armament, in spite of the considerable differences in their weight. This meant that the heavier, infantry tanks could not play a role equivalent to that of the heavy tanks of the German and Soviet armies, which were not merely more heavily armoured than the medium tanks but which were also armed with much more powerful guns. As it was, they were never expected to be a more powerfully armed complement to the cruiser tanks. Instead, they were intended to form a separate category of tanks for close cooperation with the infantry and for this purpose they were much more heavily armoured than the cruiser tanks but not more heavily armed. Thus, as a contemporary War Office publication put it, “The main differ ence between the infantry and cruiser tanks lies in the thickness of armour”

The concentration on armour protection in the development of the infantry tanks paid off at first in the case of the Matilda, which enjoyed a high degree of immunity when it was used in 1940 and 1941 in Africa against ill-equipped Italian forces. But, based as it was on armour protection, its success was cut short, like that of the Soviet KV, by the appearance of more effective anti-tank weapons. Thereafter it had to rely more on its armament and in this respect it was no better than the contemporary cruiser tanks. The same was true of its successor, the Churchill infantry tank, whose armour was progressively increased to a maximum of as much as 152mm but which, in spite of it. did not distinguish itself as a fighting vehicle.

In 1943 it was finally recognised that tank guns should not only be armourpiercing weapons but dual-purpose guns capable of delivering effective high explosive fire as well as perforating the armour of enemy tanks. Thus the final, 40 ton version of the Churchill and the 28 ton Cromwell cruiser tank were both armed with medium velocity 75mm guns. But when these tanks went into action in 1944 their armament was two years behind that of the Pz. Kpfw. IV and three behind that of the T-34. Moreover, they were no longer powerful enough to fight effectively the latest types of the opposing tanks, such as the Panther or, even more, the Tiger.

The official attitude towards this situation was that “the tank is designed with the primary object of destroying or neutralizing enemy unarmoured troops”. This may have been true during the First World War but the view implied by this statement that tanks should not normally fight enemy tanks was no longer realistic when both sides were using tanks on a large scale and fighting them could not be avoided. Nevertheless, such views persisted and so did the policy, of which they were an expression, of developing and using the two separate categories of infantry and cruiser tanks.

This policy was, in fact, the root cause of the inadequate attention given to the gun-power of British tanks and of their shortcomings during the Second World War. How serious these shortcomings were is indicated by the fact that, in spite of the relatively large number of tanks produced in Britain, in 1943 and 1944 British armoured formations had to be equipped to a large extent with US built tanks. Yet in 1941 British tank output was already considerably higher than the German and at its peak of 8611 in 1942 it was more than double the latter.

Having developed the concept of the tank to the point where it had some effect on the outcome of the First World War, you might be forgiven for thinking that Britain would have had the edge in tank design. Sadly, this was not the case! During the early years of the war, British tanks were generally not as well armed nor as well protected as their German counterparts. Rather than concentrating on a small number of designs, and developing these to the point where they were reliable, the British tank factories produced a multiplicity of often outdated and unreliable machines that reflected the questionable strategy of producing separate ‘cruiser’ and ‘infantry’ tanks.

An extreme example of tanks designed for such special roles were the infantry and cruiser tanks which the British Army employed right up to the end of the Second World War in spite of their serious deficiencies. However, in 1944 while British troops were still fighting in Normandy, their commander, General Montgomery, proposed the abolition of the division between infantry and cruiser tanks and the adoption instead of a single type of ‘capital’ tank. As it happens, the latter was eventually developed into a heavy gun tank, which was used in small numbers between 1955 and 1966. But in the meantime the policy of using a single type of battle tank was put into effect with the adoption as such of the Centurion tank in 1949.

After 1942 attempts were made to rationalise their production by the use of common components but there were still two types of tanks which differed from each other in the amount of armour and weight but not in what mattered most, namely the main armament. The final outcome of this was the A. 41 ‘heavy cruiser’, six prototypes of which were completed just as the war ended in Europe. Its engine and transmission were much the same as those of the earlier Cromwell and Comet cruiser tanks and its Horstmann bogie-type suspension was inferior to the earlier cruisers’ Christie-type independent suspensions. But its 76.2mm 17 pounder gun represented a significant advance in the main armament of the cruiser tanks and its armour protection was also considerably better. The latter included, at last, a single sloping glacis plate. The design of the A. 41 also very sensibly dispensed with the hull machine gunner, so that it had a crew of four men, which was to become general practice.

The A. 41 ‘s main armament, armour and general characteristics put it on a par with the German Panther and it was deservedly produced and put into service in 1946 as the Centurion medium tank.

In 1946 the British Army also decided at long last to abandon the policy of having infantry and cruiser tanks, which did so much harm to the development of tanks in Britain, and adopted instead the concept of a ‘universal’ tank. Unfortunately, this concept implied not only a single type of battle tank but also one which could be readily adapted to a wide variety of special roles such as flame-throwing, mine flailing, bridge-laying and bulldozing, and which would also be capable of swimming with the aid of a collapsible flotation screen. The requirement that the universal tank be adaptable to all these roles grew out of the attention which the British Army came to devote during the war to various special-purpose versions of tanks. This led to the development of several ingenious devices but it also diverted attention and effort from the basic type of gun tank. How large a proportion of the available resources was devoted to the special-purpose versions of tanks is indicated by the fact that in the closing stages of the war they accounted for a special armoured division, the 79th, when the British Army only had a total of four other, normal armoured divisions.

Between 1939 and 1945, the British Army had access to some twenty indigenous tank designs, some of them so poor that they were never to see combat, together with Lend-Lease supplies of the American Stuart, Lee/Grant and Sherman tanks. Most numerous of the home-grown tanks was the Valentine, a private venture from Vickers-Armstrongs which accounted for almost one quarter of British tank production during the war years. Others procured in large numbers included the Churchill, the Cromwell and the outdated Matilda. The standard British anti-tank gun in 1939 was the 2-pounder (40mm) and when this proved to be inadequate against the better-armoured German tanks, it was replaced by either the British 6-pounder (57mm) or the American 75mm gun, both of which packed more punch. However, none of these could compare with the German 75mm and 88mm guns and it was not until 1944, when the Comet was fitted with a 77mm gun, that a British tank could finally face the Germans on a more-or-less equal footing . . . and just 1,186 Comets were constructed, all of them too late for D-Day and the battle for Normandy!

Nevertheless, the British continue to exhibit a love of the underdog and it is our knack of snatching victory from the jaws of defeat, against all the odds, that makes British tank design so fascinating.