Veteran Austrian general defeated by Bonaparte at Marengo in 1800. Having joined as a cadet officer, he served in the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) to reach the rank of general. Recalled from retirement, he won several victories in Italy before his final defeat.

Born near Schässburg in Siebenburgen (Transylvania), Melas came from a Saxon family of Lutheran ministers and was raised in a Spartan environment, learning to ride and use weapons at an early age and attending the Schässburg Gymnasium (grammar school). At age seventeen, he joined the local Infanterie Regiment Schulenberg as a Kadett and saw action as a Leutnant (lieutenant) in the victory at Kolin (18 June 1757). Promoted to Hauptmann (captain), he commanded the grenadier company of Infanterie Regiment Batthnanyi, distinguishing himself in the storming of Schweidnitz on 1 October 1761 before becoming Feldmarschall Leopold Graf Daun’s adjutant.

Melas married Josepha Lock von Retsky on 11 September 1768. He transferred to the 2nd Karabinier Regiment in May 1778 as Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel), leading his division (two squadrons) in the War of the Bavarian Succession (1778-1779). Appointed director of the Remount Service, he was later promoted to Oberst (commanding colonel) of the Trautmannsdorf Kurassier Regiment. He led the Lobkowitz Chevauléger Regiment in the Turkish War (1788-1791) until promoted to Generalmajor on 16 June 1789 with command of a brigade. Promoted to Feldmarschalleutnant in June 1794, he commanded a small corps in Germany and repelled Kléber’s advance over the Rhine at Zahlbach on 1 December. Transferred to Italy in 1796, he commanded the Army Reserve under Feldzeugmeister Johann Peter Freiherr von Beaulieu against Bonaparte’s invasion. Briefly a temporary army commander, Melas proved an able deputy to Feldmarschall Dagobert Graf Würmser as they endured the later part of the defense of the fortress of Mantua until its surrender in February 1797. When the war concluded, Melas retired to his estates in Gratz, in Bohemia.

Despite suffering with rheumatism and what is now thought to have been Parkinson’s disease, he was recalled two years later and made Inhaber (honorary colonel) of the 6th Kurassier Regiment. As Austrian commander in Italy in 1799 alongside the Russian field marshal Alexander Suvorov, he defeated the French general Jacques Etienne Macdonald at the Trebbia in mid-June. On 15 August Melas led his troops in a furious bayonet charge at Novi against the French right flank to decide the battle for the Allies. After the Russians left, he led the Austrian troops in defeating the French at Savigliano on 18 September and Genola on 4 November before taking the fortress of Cuneo on 3 December. Melas’s surprise offensive in mid-April 1800 put Genoa under siege, and he reached the French border on the Var, at which point he was forced to return to Turin by Bonaparte’s advance. Massing his troops at Alessandria, he was defeated at Marengo on 14 June. He was appointed general commander of Inner Austria in September 1800 and then of Bohemia until 1803, when he retired.

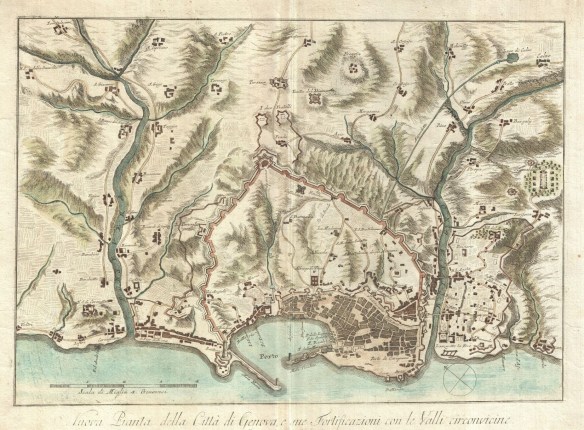

Siege of Genoa, (April-June 1800)

The defense of the last French stronghold in Italy beginning in late April 1800 played a key role in pinning down substantial Austrian forces while Bonaparte, the First Consul, crossed the Alps with his army. Despite his promises to relieve the siege, Bonaparte abandoned the defenders under General André Masséna, who surrendered in early June after enduring considerable hardship.

With promises of resupply, Bonaparte persuaded Masséna to take command of French forces on the Mediterranean coast in early February. On 6 April, the Austrian commander Feldmarschalleutnant Michael Freiherr von Melas swept south, cut the French left wing under General Louis Suchet off from Masséna, and closed the ring around the walled city on 19 April. Left with 9,600 fit troops, the French attempted forays to obtain food, but they were usually frustrated by the Austrians and their local supporters. On 24 April the Allies demanded Masséna’s surrender. He responded that he “would rather be buried under the ruins of Genoa than surrender” (Masséna 1966-1967, 3-4: appendix). Three days later, Melas left Feldmarschalleutnant Peter Freiherr Ott von Bartokez with 24,000 troops, but without heavy siege guns he could only maintain a blockade to starve the French out. The British mounted a steady naval bombardment.

The city was able to eke out meager food supplies for a month, and some local merchant ships ran the blockade to deliver highly priced corn. Bread was being sold to local inhabitants, but this was stopped on 20 May when the Austrians cut the aqueduct, which supplied waterpower for the flour mills. The military ration was reduced to 153 grams of bread-made from flour, sawdust, starch, hair powder, oatmeal, linseed, rancid nuts, and cocoa-and an equal quantity of horseflesh. However, wine was plentiful, so each man received a daily liter. Once the horses had been eaten, the city’s cats, dogs, and rats were consumed. Townspeople resorted to boiled leaves and grass, seasoned with salt, before being reduced to boiling old bones, leather, and other skins. Each day, up to 400 emaciated bodies were dumped in an open grave. The civilian population of 120,000 was reduced by more than 30,000. Austrian prisoners aboard the prison hulks received a quarter ration. They resorted to eating their shoes and leather equipment before starting on canvas sails.

On 14 May Masséna mounted one final attempt to break the blockade through Monte Creto, but he was defeated and General Nicolas Soult was captured. That night, a naval bombardment conducted by gunboats spread disorder through the population until calm was restored at dawn, when Masséna ordered any group of larger than four to be shot. A British raid on 21 May was followed by popular insurrection. On 31 May rations ran out and desertions started. Seeing no sign of relief, Masséna offered to surrender on 1 June. His parley coincided with Melas’s order to Ott to lift the blockade and march north, but the Austrians delayed his departure until 4 June, when the surrender was signed and they took possession of the city.

References and further reading Duffy, Christopher. 2000. Eagles over the Alps: Suvorov in Italy and Switzerland, 1799. Chicago: Emperor’s. Hollins, David. 2004. Austrian Commanders of the Napoleonic Wars. Oxford: Osprey. Furse, George. 1993. Marengo and Hohenlinden. Felling, UK: Worley. (Orig. pub. 1903.) Hollins, David. 2000. Marengo. Oxford: Osprey. Masséna, André, prince d’Essling. 1966-1967. Mémoires d’André Masséna. 7 vols. Ed. Gen. Koch. Paris: J. de Bonnet (Orig. pub. 1848-1850.)