Mountbatten had been obliged to assert his authority at the outset of his command and did so, the integration of the Allied air forces proceeding as outlined below:

Air Command South East Asia

Allied Air Commander-in-Chief, Air Chief Marshal Sir Richard Peirse RAF.

Eastern Air Command (EAC)

AOC and second in command to Peirse, Major General G.E. Stratemeyer USAAF, his position in respect of the Allied air forces corresponding to that of General Slim’s for ground forces. EAC was organized into the following groupings:

- The Third Tactical Air Force commanded by Air Marshal Baldwin and subdivided into:

(a) The American North Sector Force with responsibility for supporting Stilwell’s Chinese and protecting the air ferry route over the Hump to China.

(b) 221 Group RAF under Air Vice-Marshal Vincent, with headquarters at Imphal and responsible for the support of IV Corps along the main central front.

(c) 224 Group RAF under Air Commodore G.E. Wilson with headquarters at Chittagong and supporting XV Corps along the Arakan front.

- The Strategic Air Force, Brigadier General Davidson USAAF.

- Troop Carrier Command, Brigadier General W.D. Old USAAF.

Stratemeyer established his HQ in a huge jute mill near Barrackpore, while Baldwin’s Third TAF and Brigadier General Old’s joint US-British Troop Carrier Command HQs were set up alongside General Slim’s Fourteenth Army HQ at Comilla. To a considerable extent the three headquarters operated as a joint command centre, pooling intelligence, planners working together and perhaps most significantly, the three commanders and their principal staff officers living in the same mess. Slim reports that integration reached the stage where Americans adopted the tea-sipping habit and the British learned to make drinkable coffee!

By November 1943 approximately two thirds of theatre combat aircraft were British, the remainder American although the US proportion was increasing, notably in the area of transports. The USAAF had begun the supply of Chinese-American forces in north-east Burma with the 1st and 2nd Troop Carrier Squadrons, which in January 1944 were joined by two additional units, 27th and 315th Troop Carrier. During the winter of 1943/44 the RAF too built up its tally of transport units, Nos 31 and 194 also being reinforced by two additional squadrons:

No. 62, previously operating Hudson Mk VI aircraft on bombing and general reconnaissance duties, converted to Dakotas in early January 1944.

No. 117, a veteran transport outfit, arrived from the Middle East, initially operating DC2s but converting to Dakotas in July 1944.

194 Squadron, operating the Hudson Mk VI on internal trans-India operations since its formation, converted to Dakotas in February in order to take its place alongside ‘parent’ squadron No. 31, its previous duties being taken up by 353 Squadron.

An essential part of Mountbatten’s approach was to be seen and heard by the men who would have to do the fighting. To achieve this he embarked on a tour of the military units of all nationalities, and Wilfred Goold describes one such visit by the Supreme Commander to 607 Squadron:

On December 16 Lord Louis Mountbatten arrived on our strip and I was one of four to escort his Mosquito over the forward areas. He gathered everyone around him and told us of his plans and then told us what he expected of us. There was no doubt this time; there was no turning back.

The informal ‘gathering everyone around’ appears to have been an essential part of Mountbatten’s attempt to make sure that everyone felt included, from the C-in-C to the cooks and admin clerks, they were all in this together and they all had their essential part to play.

While command changes took place the air war continued. Operating from bases in Assam the 311th Fighter Bomber Group USAAF attacked targets in Northern Burma. On 25 November Major Yohei Hinoki of the 64th Hikosentai intercepted a raid and led the 3rd Chutai in an attack with their Ki-43 Oscars. In the ensuing dogfight Hinoki shot down the first North American P51 Mustang of the Burma campaign, the aircraft piloted by Colonel Milton, Commanding Officer of the 311th, who became a POW. Two days later Hinoki’s 3rd Chutai intercepted an estimated fifty B24 Liberators plus thirty fighters, Hinoki claiming a P51, a P38 Lightning and a B24, but falling victim to another P51. Badly wounded, Hinoki managed to return to base but his right leg required amputation and he was repatriated to Japan to take up training duties.

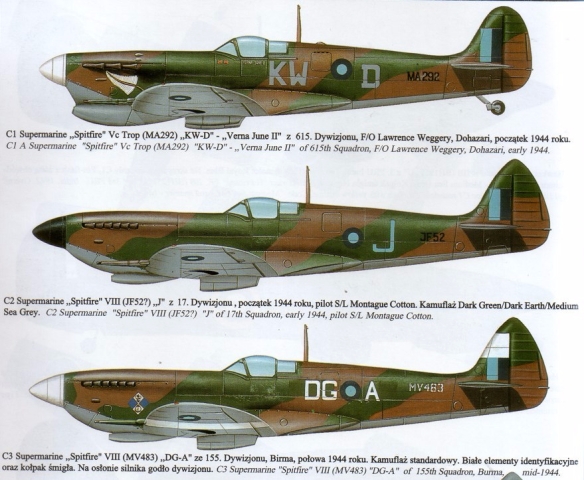

Spitfire Mk Vs at last began to appear in an operational role and much was expected of them. Up to this time the twin-engine Mitsubishi Ki-46 Dinah reconnaissance aircraft employed by the JAAF had flown with impunity over Allied territory, its service ceiling and maximum speed too much for Hurricanes and other Allied fighters. However, in November 1943 Spitfires from 615 Squadron RAF based at Chittagong shot down four Dinahs from the 81st Hikosentai in quick succession and the news spread rapidly through the entire Allied command, providing a tremendous boost for morale as it did so.

The unexpected loss of their reconnaissance aircraft was a blow to 5th Hikoshidan but also gave them some indication of the power and performance of the new Allied fighter. Despite losses in aircraft and experienced pilots 81st Hikosentai continued missions in the Calcutta area and reported a large concentration of some sixty merchant vessels in the harbour – a target too good to miss. Wary of the Spitfires the JAAF attack formations planned a route well to the south of the Chittagong airfields at which they were based, while 8th and 34th Hikosentai (20 and 15 light bombers respectively) accompanied by 50th and 33rd Hikosentai (27 and 20 fighters respectively), plus 5 Dinahs of the 81st Hikosentai, carried out raids in the Chittagong, Silchar and Feni areas to keep the new fighters busy and off balance.

607 Squadron was based at Ramu at this time, a dirt airstrip south of Chittagong, and Wilfred Goold remembers a pattern of almost daily ‘scrambles’ to combat these raids:

The tactics we were using were similar to those used by the Luftwaffe against our Hurricanes i.e. height advantage, then diving in, attacking and regaining height. The Japs used what we called a ‘Beehive’ [aircraft flying in circles] from a basic height up to about 25,000 feet. They were very colourful, highly polished, except for about a dozen, who, we learned, were the ‘aces’, they flew in drab coloured Oscars.

Our radar was very good so we were always in the top position, but they were so manoeuvrable that zip, and they were gone.

With additional raids having being staged in the Imphal area for weeks beforehand to draw off Allied fighters, the primary attack on Calcutta took place on 5 December and involved units of both the JAAF and JNAF, operating in two waves from Burmese airfields at Magwe and Allanmyo:

JAAF

7th Hikodan, comprising:

12th Hikosentai (9 heavy bombers)

98th Hikosentai (9 heavy bombers)

50th Hikosentai (27 fighters)

64th Hikosentai (27 fighters)

33rd Hikosentai (20 fighters)

204th Hikosentai (20 fighters)

81st Hikosentai (2 Dinahs to drop quantities of streamers just prior to the raid to confuse Allied radar).

JNAF

28th Hikotai (Flying Unit) comprising 9 medium bombers and 30 Zero fighters.

The plan to evade the Spitfires worked and although the raid was picked up by Chittagong radar, of the sixty-five Spitfires and Hurricanes scrambled to intercept only one Spitfire made contact, shot down a bomber and force-landed on a sandbank out of fuel. At Calcutta itself the defending Hurricane Squadrons, Nos 67 and 146 RAF, were overwhelmed by the raid’s fighter defence and lost eight aircraft – the JAAF believed that they were only attacked by about ten aircraft in total. When the second wave of the attack swept in the Hurricanes were caught on the ground refuelling and only a few night fighters were able to get airborne. Two Spitfire squadrons from Chittagong attempted to intercept the raiders as they returned, but were again unable to make contact.

The raid had been carefully planned and executed and was an undoubted tactical success for 5th Hikoshidan, who were jubilant at having got off so lightly. Nevertheless, to gain the range for the long southward leg to avoid Chittagong the bomb loads had been necessarily small, consequently the damage inflicted, while unwelcome, was not devastating. Three merchant ships and a naval vessel were damaged, fifteen barges set afire, and a number of dockyard buildings destroyed. By far the most damaging aspect of the raid was the 500 civilian casualties caused, followed as it was by an immediate exodus of the local population from the docks area.

Encouraged by their success the JAAF planned further raids on Calcutta but first, having attacked the port at the far south of the Allied positions, they switched their attention to the far north – the trans-Himalayas ‘Hump’ route to China. As part of the Calcutta attack plan fifty fighters and eighty light bombers from 4th Hikodan attacked Tinsukia airfield on 8 November to disrupt the China supply route and keep Allied attention away from Calcutta. Following the raid on Calcutta 4th Hikodan commenced a series of raids on ‘Hump’ airfields inside China with Tinsukia again being the target on 11 and 12 December, followed by Yungning in succeeding days. On 18 and 22 December Kunming received the attention of seventy fighters and bombers of 7th Hikodan plus around ten heavy bombers specially brought in for this attack on the principal ‘Hump’ airfield in China. JAAF fighters also attacked transports in flight over northern Burma and for a time as many as three per day were being destroyed, but the supply route remained in operation.

Without sufficient resources to attack all its potential targets in strength simultaneously the JAAF once again turned its attention to the south, this time to the bustling port of Chittagong – and the Spitfires they had thus far gone to considerable lengths to avoid. On Christmas Day 1943, 7th Hikodan attacked the port with an estimated twenty bombers and thirty fighters. As an illustration of the way in which Allied air strength had grown over the past year the defences were able to put up eighty Spitfires and Hurricanes, but the result fell far short of expectations. If the availability of aircraft was now not as pressing a problem, the shortage of radar and ground-to-air communications equipment with which to vector fighters on to attacking aircraft effectively – plus trained operators – most definitely was. The uncoordinated mêlée of Allied fighters posed much less of a threat to the disciplined JAAF formation than it should have done if properly controlled, and a tally of three bombers and two fighters shot down was disappointing.

One Spitfire pilot, John Rudling, developed a highly unusual method of attack. With his squadron newly equipped with Spitfires, Rudling was returning to base following what up to that point had been a fruitless sortie. Noticing enemy bombers in the distance, and despite his fuel being down to ten gallons, Rudling headed toward them and swooped in to the attack. Opening fire on a bomber, Rudling

observed strikes on the enemy’s wings when I suddenly realised I was going to collide. I broke sharply away above, feeling my aircraft hit the rudder of the bomber. I then proceeded down, thinking I had damaged my aircraft for any further attack, but it was all right, so I pulled up under another vic [‘V’ formation] of bombers, firing from underneath at the leader.

A Japanese fighter attacked the lone Spitfire and hit the aircraft with five shells, damaging the oil tanks. Rudling watched the bomber with which he had collided spiral down into the sea then force-landed himself without flaps or brakes. The RAF pilot became so attached to the collision method for downing bombers when his ammunition had expired that he tried it on succeeding occasions, and it was not until his third attempt that he was himself, perhaps unsurprisingly, killed.

So far the Spitfires had shown promise but had not really been able to get to grips with their opponent, however that was about to change. On 31 December 1943 a substantial JAAF force comprising fourteen Ki-21 Sally light bombers and fifteen Ki-43 Oscar fighters, attacked a Royal Navy force that had been bombarding Japanese forces along the Arakan coast. Scrambling from an airfield in the vicinity of Chittagong, twelve Spitfires of 136 Squadron RAF intercepted and broke through the fighter cover to find the bombers flying in perfectly disciplined ‘V’ formation – a formation resolutely maintained by the Japanese as the RAF fighters shot them down, one by one. Having completely destroyed the bomber force the Spitfires set about the Japanese fighters and in a series of dogfights destroyed the majority of the typically brightly coloured Oscars, those that did survive limping home badly the worse for the encounter. One Spitfire was lost, the pilot having a lucky escape as he descended by parachute. An Oscar swept by and machine-gunned the helpless airman, but the Japanese pilot misjudged his approach and crashed into the ground. This was the first substantial victory that the RAF, and certainly the new Air Command South East Asia, had been able to achieve over the JAAF and was without doubt a turning point in the air war.

On 15 January the JAAF tried again, this time the intended target being Chittagong itself, however the plan was for three fighter sweeps of between twelve and fifteen aircraft apiece to attack the Arakan battle area to draw off defending fighters and leave the port open to the bombers. As early morning mist lifted the first attack materialized and the Spitfires were scrambled. The Japanese pilots might well have been smarting from a loss of ‘face’ stemming from their defeat at the turn of the year, as they appear to have adopted do-or-die tactics in their efforts to come to terms with their opponents; but fanatical courage was not enough. Sixteen Oscars were destroyed at a cost of two Spitfires. On 20 January the JAAF tried again, 35 Oscars engaging 24 Spitfires and losing 7 of their number for 2 RAF aircraft.

With these battles the RAF wrested air superiority from the JAAF for the first time in the south, but the Japanese did not let it rest there and introduced the Ki-44 Tojo in greater numbers to counter the Spitfire Mk Vs, coupled with new tactics. JAAF fighters would usually be painted in the ostentatious colour schemes of their particular Hikosentai but now a few appeared with either their aluminium skins highly burnished to a mirror-like finish, or alternatively painted jet black, both colour schemes designed to be observed with ease from a distance. A few of these decoys would fly well below more numerous camouflaged aircraft in the hope of trapping Spitfire pilots, who soon learned to be wary of such glittering prizes. Fortunately for the Allies the much improved Spitfire Mk VIII made its appearance and with its true air speed of 419mph in Burmese conditions, plus a service ceiling of 41,000 feet and faster rate of climb than the Spitfire Mk V, the JAAF was checkmated again. To the north, however, the issue of air superiority was still very much in the balance and it was to this sector that the scene of action once again moved, with 5th Hikoshidan using its entire fighter strength to attack transport aircraft on the Hump route in the skies above Sumprabum in northern Burma.