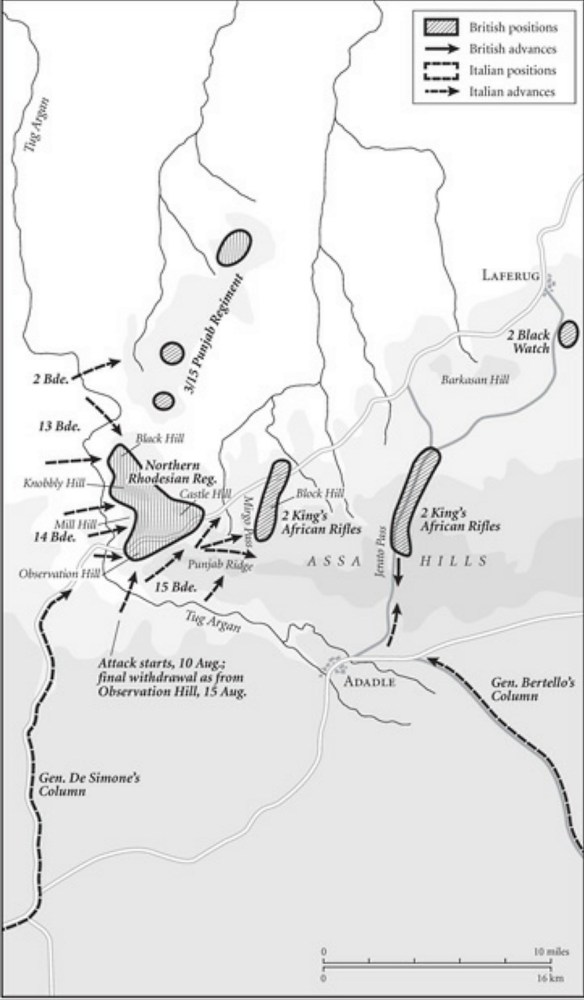

Defence of the Tug Argan Gap.

Throughout this period Wavell was away from Cairo, having been summoned back to London by Churchill. The Middle East commander had many admirers but the prime minister, in office for two months and having inherited all of the senior military commanders from his predecessor Neville Chamberlain, did not appear to be one of them. The men had their first disagreement in early June when the general in Cairo had been instructed to send back to Britain from Palestine eight battalions to help man the country’s defence against the anticipated German invasion. Wavell was unwilling to reduce his very limited forces and the troops were not sent, a decision which Churchill apparently never forgot. Their differing opinions on how to resource and conduct operations in the Middle East were undoubtedly the principal source of friction, but the military commander’s character proved incomprehensible to the politician and Churchill’s resulting loss of trust in Wavell encouraged his tendency to become embroiled in operational and tactical details of battle. In late July one well-placed observer in the War Office noted that the prime minister had decided to send for Wavell ‘for personal consultation’, but it had proved possible to persuade him that removing a senior commander for several weeks when an attack might come at any time was not the best course to follow. Even then Churchill apparently only accepted this delay reluctantly, reversing the decision a few days later and leading to Wavell’s ‘flying visit’. This was seen by many as an early, very clear indication of Churchill’s lack of confidence in his commander and his abilities.

At the same time, and despite the now obvious extent of the Italian military advantage, in London the prime minister and the Middle East Committee were still anxious that the garrison in British Somaliland should hold out. This led to the decision to send a battalion of the Black Watch, which had been kept in Aden as a reserve, to join the four others already there, making, it was argued, a potentially potent force. With only one transport ship available it would, however, take three days for it to be moved and assembled alongside the existing formations. As a further demonstration of this sudden new-found commitment, enquiries were also made as to whether 1st Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment could be transferred by a fast cruiser, and it was even suggested that medium tanks might be sent, although this idea was quickly amended to the possibility of making some Bren gun carriers available instead. Further discussions also took place about improving the port facilities at Berbera: Wavell had expressed his concern about their poor quality the month before, particularly for maintaining the flow of supplies or, possibly, managing the evacuation of troops. He had warned then about the danger of ‘congestion and confusion’ but there was no time for this to be remedied. As the fighting around him became increasingly desperate, detailed instructions were now sent from London to the base commandant for the long-term improvements that were to be made. This was a positive step but it had come much too late and pointed to how little understanding there was of the impossible task facing the defenders and the desperate battle that had already begun.

With this heightened interest in London, the headquarters in Cairo was also asked to develop an updated appreciation and proposals for what would be needed to retain control of the protectorate. In Wavell’s absence, one of his senior colleagues was quick to offer a view of regional strategy which seemed to run counter to those held by the general. Air Chief Marshal Longmore noted that out of a force of 187 bombers and fighters in Italian East Africa and Eritrea, only 39 were believed to be operating against British Somaliland. He also stated that, whilst the total available to them appeared to represent a significant advantage, the Italians actually faced serious problems in maintaining their forces. Longmore wrote that, at their present rate of consumption, the enemy would have no more than seven months of fuel and faced potentially critical shortages of ammunition, bomb components and aircraft spares. Mindful of both the increasing threat facing Egypt and the successes being achieved by aircraft based in the Sudan in attacking Italian frontier posts and supply bases, Longmore argued that nothing could be spared to help defend the protectorate. All he was prepared to contribute to its defence was sending long-range bombers to attack key objectives in and around Addis Ababa which, he argued, might draw off some of the advancing Italian troops. There was in fact only a remote prospect of this offering any real respite to the defenders in British Somaliland and it highlighted once again the reluctant commitment to its defence which had, since at least 1938, been such a common feature of official policy.

Another decision made in London, which reflected the increased size of the garrison, was to appoint a more senior commander to lead the protectorate’s defence. Major-General Reade Godwin-Austen, who inherited the unenviable task, was another professional soldier who had been commissioned from Sandhurst in 1909 into the South Wales Borderers and had fought throughout the First World War in the Middle East, where he received a number of awards for bravery. During the inter-war years he spent periods based back in England but for most of the time he was in Palestine. Wavell thought highly of him, and in August 1940 he had been poised to take command of the 2nd African Division when instead he was ordered to proceed to Berbera as quickly as possible. According to Arthur Smith, when the general was woken in the early hours of the morning to be told that he was to leave Cairo at 6 a.m. he reportedly responded with a booming voice, ‘Godwin will be there’, before going back to sleep for a few more hours. Prior to setting off to take over his new command he was provided with a single page of instructions with only six points and a brief administrative appendix. The first confirmed he had been appointed to replace Chater, and the next gave him the authority to organise the command as he wanted, with advice that he remain closely in touch with the Senior Naval Officer and Air Officer Commanding in Aden. The strategic advice was brief: he was to prevent any advance beyond the main established defensive position and, whilst the immediate role of his troops was defensive, any opportunities for local offensive operations were not to be overlooked. At the same time he was to prepare for withdrawal and evacuation, although this possibility was to be disclosed to the bare minimum of people.

On reaching the protectorate Godwin-Austen followed his additional instructions to relieve Glenday and also take over civilian administration of the territory alongside his military role. Although he had only just arrived it was already clear what had to be done and on the evening of 14 August he wrote to Cairo to suggest that the position was becoming hopeless. His principal concern was that there was no possibility of concentrating the dispersed forces he still had available which were covering various passes and the routes through them towards the port. Each of the outposts knew it had to hold out for as long as possible, but as there were not enough reserves to provide adequate support the Italians could infiltrate on foot the unmanned openings. As he put it, this meant ‘there was no defensive position close in [and] defending Berbera which cannot be outflanked’. The general was also facing difficulties in receiving instructions from Wavell as a shortage of staff and the increased number of messages being sent meant that some were left undeciphered for up to thirty hours. Further hampering him were the limited means of communicating between his units and he had grave doubts about the ability of the African and Indian troops to stand up to concerted Italian artillery fire. This final point was prominent in his calculations as he was concerned about the effect that ‘a serious disaster’ could have on British and Commonwealth troops elsewhere.

By the following morning it was growing obvious that those men who remained in the forward positions were exhausted and shaken by the continuous bombardment they had experienced for several days. Godwin-Austen assured the headquarters in Cairo that his forces were willing to fight on ‘if total sacrifice of forces considered worth it’, but at this stage he believed evacuation would allow for about 70 per cent of them to be saved. He therefore decided to fall back on the port and orders were issued to withdraw. General Maitland ‘Jumbo’ Wilson, deputising for Wavell while he was in London, had received a series of messages from Berbera warning that the situation was critical and this led him to accept the advice and issue the code-word ‘Snipe’. As he later wrote, ‘I had no hesitation in agreeing to immediate evacuation’ as ‘we could not afford to waste a single soldier for the heroics of defending to the last man a territory which a year previously was not considered to be worthwhile’. Having indicated that he still had large numbers of men he could pull back to the port, Godwin-Austen was, however, told that it was assumed this final position could then be held for some time. Instructions were also given that, whilst he was not to prejudice the success of the evacuation, he should try and save his heavier equipment. Exactly this type of operation had previously been identified as being fraught with difficulties in a report that had examined the possibility of evacuation the month before the Italian attack began. It noted that it would be impossible to bring ships alongside due to the poor quality of the harbour facilities, and boats would have to take the troops off from the wharf. Using this method and with access to three large naval vessels, one of which would need to be a cruiser, it was calculated that 1,000 men could be moved each day but all 350 vehicles and the bulk of the stores would have to be left behind. This forecast proved entirely accurate and little of the transport was recovered. Parts were removed to disable vehicles but no attempt was made to destroy them as it was feared fires might illuminate the town and allow the Italians to interfere with the escape. At least all of the troops were safely evacuated, the only exception being those of the Camel Corps, most of whom were simply told to return to their homes and await the return of the British. Previously they had been told that in the worst case they were to hold as much territory as they could and harry the occupying Italians, but this plan had apparently now been set aside.

With the withdrawal complete, on the morning of 19 August HMAS Hobart’s guns shelled Berbera for two hours and destroyed key structures including government buildings, barracks and storehouses. One of those on board recorded the final scenes: ‘as we steamed out we could see the Italian forces in the hollow of distant hills waiting to move in when our guns had finished firing. As we steamed away we watched eagerly to see if there might not be one more man to be saved from the shore before it receded from our sight.’ Another witness, a British colonel standing on the same deck, said it reminded him of the Gallipoli evacuation. The warships stayed on for a few more days and kept in touch with stragglers, rescuing those who had not been able to make it back to Berbera. After taking aboard a final group the small convoy set sail for Aden, arriving later the same day. Some of the Indian troops eventually remained there but most of the evacuees headed straight for Kenya and Egypt. The end had been relatively swift, no more than a couple of weeks in total, but the impact of this defeat would rumble on for far longer.

Vice Admiral Sir Geoffrey Blake, Additional Assistant Chief of Naval Staff at the Admiralty in London, was saddened to hear the news of the withdrawal but wrote to the Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean:

I don’t think, except from the point of view of prestige, that it is going to have any very great effect on the strategical position vis-à-vis Aden, but nevertheless, it seems to me a thing which should not have occurred. It appears to have taken the Military Authorities at home here quite by surprise, and it was only a matter of about 10 days ago that they were talking quite hopefully of the position in the hills being maintained indefinitely until reinforcements arrived at Berbera. Apparently their information must have been rather faulty as they seemed to have no idea of the number of tanks and other armoured vehicles which the Italians appear to have had available to them.

Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham replied that he also regretted what had happened and that ‘the soldiers were caught with their trousers down’. This was a more accurate description than he might have known. Although the need for their evacuation had been recognised as a possible outcome of an Italian attack, the issuing of the actual order had not been anticipated by the British colonial officers who still remained in Berbera, and many of them arrived in Aden with little more than a pair of pyjamas.75 A post-war review concluded that if the port facilities had been improved as had been recommended, most of the transport could have been saved, but there was an ‘insistence on running our Colonies “on the cheap” especially in matters of defence’.

Despite what had happened, Britain’s media tried to remain positive. Once the fighting had begun to grow in intensity and the narrative had started to point to the protectorate’s possible loss, the argument that this was not that critical an element of the imperial network had begun to play out. One commentator wrote that it was simply of ‘scant account’ in the overall strategic picture, while others highlighted the idea that the Italians were in fact being deliberately encouraged to wear down their manpower and resources. As late as 12 August it was still being reported that the invading forces had not reached the main defensive positions when the final battle was in fact already poised to begin. In all these accounts Berbera was consistently referred to as being important and it was argued that there was never any intention of surrendering the port. Such statements exposed the initial lack of recognition by the media and the public at large that the situation was so desperate. An editorial in the Manchester Guardian three days later argued that there was still an opportunity to inflict a setback on the Italians by mounting a successful defence, and called for more troops to be sent. This also noted that the official statements referred to the situation as ‘serious but by no means critical’, which was reminiscent of the comments made in France before its final collapse. Even when news arrived that the withdrawal back to Berbera had begun, correspondents on the ground remained optimistic that the British and Commonwealth troops would be able to hold on to the port. One writer for The Times described the Italian forces across the region as ‘a beleaguered army which must live on its reserves of supplies and whose only hope of survival is that Hitler may pull Mussolini’s chestnuts out of the fire by winning the war elsewhere’. Whilst this assessment was, of course, entirely correct, and would later be shown to be exactly what the Italians were also thinking, it was some time before this would become known and did little to help the situation.

#

Militarily, Wavell had done nothing wrong; indeed, with the disparity between the opposing forces in the protectorate it was remarkable that the defenders were able to hold out as long as they did. The Battle of Britain was, however, in full flow and there was no Churchillian appetite for a defeat that could not be portrayed in heroic tones. The prime minister’s vision of strategy may have had moments of genius but it was also often based on acts of heroism and sacrifice, not the logical use of force and the notion that it is sometimes preferable to wait for a better opportunity to secure a decisive victory. Churchill was wrong to condemn Wavell and his subordinates for their entirely reasonable actions, but one of the steps he had taken when he assumed leadership of Britain only a few months before was to appoint himself as the first ever Minister for Defence. It was this title that offered him the conviction that his way was the only way and there would be consequences for those involved in the defeat.

The loss of British Somaliland marked the first redrawing of the British Empire’s map since 1931 when a strip of land in the Sudan had been ceded to Italy. Godwin-Austen admitted that he smarted about what had happened and it drove him on during the subsequent campaign to show the Italians ‘what being overwhelmed by numbers and superior armament felt like’. Hitler apparently referred to it as ‘a hard blow to British prestige’, but it was actually more an emotional setback than a military one. As one contemporary writer put it, ‘all the British had lost was the privilege of maintaining an expensive garrison in their least valuable colony’. And the outcome could have been much worse. Aosta wrote after his own eventual surrender the following year that the key theme of his plan had been speed and his commanders had been urged to move on as quickly as they could following Berbera’s capture. Difficulties in getting supplies forward, particularly food and water, along with some very poor weather and heavy rains which rendered some of the roads impassable, made this difficult to achieve. Having encountered the strong defences around Tug Argan and the additional delay they imposed, Aosta made an attempt to send troops forward by aircraft and a force of 300 volunteers was readied to make a bold attempt to seize the port; but the only landing ground was in British hands and so the plan was abandoned. If it had not been, the haphazard and poorly defended evacuation could easily have been disrupted and some, or even all, of the withdrawing forces captured. Once again, the Italians had failed to exploit the opportunities presented to them and within a matter of months this high point of victory would seem a distant memory.