The Admiralty was obliged to find an effective response to the U-boat menace. This form of economic warfare was proving highly effective with these silent predators being free to strike undetected and at will. It was impossible to provide sufficient warships to patrol the coasts constantly, and even swift destroyers had a limited range of weapons and tactics to deploy. One possible remedy was to find a mongoose to take on the U-boat cobra, and the response was the ‘Q’ ship. Quite simply, this was a trawler or small merchantman, ostensibly too puny to merit the cost of a torpedo, best dealt with by gunfire from the U-boats’ deck-mounted weapons. But this target would not be as defenceless as it appeared. As the submarine surfaced and closed in for the kill, the victim would suddenly sprout an arsenal of its own and take the predator on in a surface gun duel, hunter thus becoming hunted. By the spring and then summer of 1915, a number of such vessels were in operation but without scoring any significant hits. However the armed collier Prince Charles was destined to do rather better.

Prince Charles was part of the vital collier fleet, which performed the necessary but unglamorous role of maintaining coal supplies to the fleet at anchor in Scapa Flow. Lieutenant Mark Wardlaw RN commanded a ten-man naval detachment on the small vessel, armed with a brace of concealed, small calibre guns. On the evening of 24 July 1915, one of those endless days in the Orcadian summer, U-36 had stopped the Danish vessel Louise but decided the collier offered a more tempting prize. As the chase developed, the U-boat opened fire at extreme range with her deck guns. Wardlaw then responded by ordering the civilian crew to heave to and abandon ship as though in panic. U-36 slid in to a range of 600 feet, confident of the kill. She was simply not ready when Wardlaw unmasked his two guns to commence a steady and accurate fire. This vital element of surprise proved crucial. The Germans were badly shot up and, as they attempted to dive, Warlaw’s gunners finished the job, sending U-36 to the bottom and taking 15 survivors prisoner.

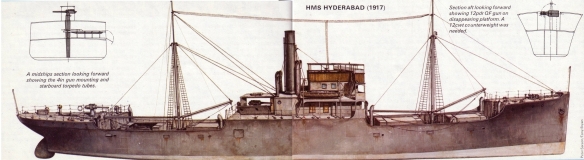

This neat little action showed the worth of the Q-ship, and northern waters became a frequent hunting ground. These were, by definition, never proud men-of-war. In fact, the more down-at-heel the Q-ship appeared, the more likely she was to successfully tempt a U-boat into a surface attack. Occasionally, such a craft might carry torpedoes but more typically a number of smaller guns which could be easily hidden, along with machine guns and small arms. Deception was the key; naval crew had to blend perfectly into the less formal regime of a tramp merchantman. A U-boat would stalk her potential victim long before she surfaced, so the sailors had to look scruffy and unmilitary. This façade had to be maintained in port lest enemy agents be vigilant. Such men were in the mould of Drake and Raleigh. One could imagine Sir Andrew Wood or Cochrane fitting into such a role with gusto. The ship itself was an integral part of the ruse. She would be camouflaged and repainted lest her former lines become too familiar and thus suspect.

When a U-boat surfaced and rode in for the kill, deception reached its final theatrical denouement. A portion of the crew, equal in size to what might be expected of a merchant vessel of this class, would run around the decks, giving ample signs of incipient panic. After a decent interval, they would abandon ship with the captain or someone who looked like a captain, ostensibly clutching the tempting lure of her papers. This finely judged performance (as indeed it might be, as the sailors’ lives depended on the reactions of the predator) was intended not only to maintain the deception but to draw the U-boat on, till the range had closed and the Q-ship’s guns were suddenly unmasked.

Memories of the slaughter of Lusitania’s hapless passengers as a consequence of German action were still fresh, when the Q-ship Baralong steamed to the aid of another liner, Nicosian, attacked in the Channel by U-27. The German decided to punish the shabby tramp steamer for her impudence, but suddenly found herself under fire from the Q-ship’s 12-pounders. Lt Commander Herbert, having crippled his opponent, showed no mercy to the desperate survivors. Numbers were shot in the water or as they sought to climb aboard the liner; total war was by no means a one-sided business. As pressure on Germany mounted, the attraction of unrestricted submarine warfare re-emerged as strategic doctrine; the U-boat fleet could put over 130 craft into the water, with technical capability being continuously enhanced.

Typically, a hunter type U-boat now had four tubes forward with two aft and either a pair of 86-mm, or a single 105-mm, deck-mounted guns. These formidable predators had, by the end of 1916, accounted for a staggering 443,000 tonnes of Allied merchantmen. Jellicoe cautioned that, with this rate of loss, Britain would be hard-pressed to maintain the war effort through the following year and on her knees by the summer. It was small wonder that Haig’s plan for a summer offensive in Flanders included the notion of an amphibious assault on the U-boat pens located within the German-held Channel ports. Sensing that the U-boats might yet achieve what German armies had not and break the will of the British Empire, Wilhelm II agreed to the resumption of totally unrestricted submarine warfare. Losses of allied merchantmen continued to spiral.

BEATING THE U-BOATS

One response to the U-boat menace was the convoy system. This was a tried and tested expedient, but one which the Admiralty had, initially, resisted, fearing that to concentrate ships in large numbers would provide nothing more than a submarine feeding frenzy as the ‘wolf packs’ circled. It was not until May 1917 that a system was put in place, though convoy sailing was not obligatory for merchantmen. Losses, however, did begin to decline. The new system was complemented by the introduction and laying of improved mines and, critically, by a significant innovation, the D Pattern Mark III depth charge. These ungainly, underwater explosive devices, little more than a container filled with high explosive and set to detonate at a fixed depth, were used first in action during July 1916, though it wasn’t until December of the following year that depth charges sank UC-19.

Improved means of launching projectiles and the hydrophone system of underwater detection, combined with maritime air patrols, began to turn the tide, to nibble at the U-boat’s supremacy and finally chew it to pieces. In May 1918, some 16 U-boats were sunk. Operational life-expectancy of a submarine crew reduced to six weeks, leading to an even greater savagery on the part of U-boat commanders as time ran out. And time was indeed running out. On 22 October 1918, U-boats were ordered to refrain from further attacks on merchantmen, and it was German sailors who responded to Bolshevik calls for an armed revolution. When it was all over, time to count the cost: 5,000 Allied ships had been lost and with them 15,000 lives; the U-boat service had lost 178 craft and almost half its complement of 13,000 sailors. This First Battle of the Atlantic had been a very close run thing indeed.

CAPTAIN CAMPBELL

For all their swashbuckling, the Q-ships proved the least effective of the Allies’ responses. Depth charges and hydrophones, linked to more and more effective mines, and the shepherding of the convoy system, combined to defeat the U-boats. Of the 180 Q-ships deployed, only 10 managed to destroy German submarines, 14 in all. One of the most successful captains was Gordon Campbell who, commanding Farnborough in March 1916, sank U-68. Then, just less than a year later, accounted for U-83, losing his ship in the process but winning a Victoria Cross. On 8 August 1917, he was master of Dunraven, a converted merchantman, which refined the Q-ship concept by carrying some minor but visible armament, her additional firepower concealed. On that summer’s morning, she was engaged by UC-71 and a rather desultory exchange of fire resulted in no damage or loss to either hunter or hunted.

When this opening exchange had spluttered on for half an hour or so, UC-71 motored in for the kill. Her guns were now striking the superstructure, starting a fire in the poop-shack that threatened to spread to a small magazine. It was now 12.10 p.m. and the action had continued for nearly an hour. The ‘panic crew’ had already played their part, but one of the gun crews was horribly exposed if the magazine ignited. Nearly 50 minutes later the inevitable explosion occurred, wreaking carnage on the after decks and killing one of the gunners. Amazingly, the rest survived, though by no means unscathed. An injured lieutenant apologised to Campbell for leaving his post without orders! The captain had already issued instructions for his remaining guns to open fire, but the U-boat dived unscathed. She was still the hunter and the badly damaged Dunraven still the prey. A torpedo struck at 1.30 pm, blowing out a section of hull. The master ordered all but the remaining gunners to abandon ship, but the German commander, Leutnant Saltzwedel, was not disposed to take chances. Over an hour later, as the Q-ship was already settling, UC-71 surfaced astern to conclude matters with gunfire. Campbell described the ensuing bombardment as extremely unpleasant – in the circumstances, something of an understatement!

Dunraven was wallowing, without sufficient power to turn and return fire upon her tormentor, who now dived once more and circled, like a hungry shark. Campbell promptly loosed two torpedoes of his own, but only one came close and that not close enough. Dunraven was clearly doomed. Campbell stayed aboard with only a single volunteer gun crew. But time was also running out for the Germans: UC-71 could not afford to hang around indefinitely to finish the dying ship and most of her ammunition – shells and torpedoes – was now expended. She withdrew, and Campbell might at least claim the fight as a draw. A destroyer took the crippled Dunraven in tow; she eventually foundered, though without further loss of life. The lieutenant and petty officer who’d stuck to their gun even as the magazine smouldered beneath their feet each won a Victoria Cross. If the Q-ships were not a successful measure in terms of the strategy of the Battle for the Atlantic, this was no reflection of the extreme gallantry of their officers and crews.