Two years before the 1848 eruption, tremors could be felt in Italy, and in Galicia where a revolt of the nobility was put down vigorously by the prompt action of an energetic young officer called Benedek. His less energetic contemporary, General Collin, further to the west, panicked and surrendered the city of Cracow to the insurgents, who promptly declared a national republic. But these events only illuminated the sky like flashes of lightning before the storm; they gave no inkling of what was to happen in Vienna two years later. The build-up to the revolutions of 1848 is known as Vormärz (pre-March) and describes the accumulation of perceived injustices and frictions which are ever the prelude to a popular uprising. As time passed, the innate conservatism of the system left it increasingly vulnerable to new challenges.

In Vienna, events finally came to a head on 13 March 1848. Students, the potential leadership of any revolt, armed themselves and began issuing a list of demands. These included press freedom, the abolition of serfdom, and, above all, the removal of the detested Chancellor Metternich who had come to personify cynicism, reaction and absolutism.

In the War Ministry, the minister, Latour, comprehended only too well the scale of the seismic challenge he now faced. He ordered a detachment of artillery guarded by a detachment of ‘pioneers’ along the Herrengasse. These were greeted with a hail of stones and, as the pioneers panicked and shot back, five civilians were killed. In the nearby Arsenal, Latour was surrounded by a violent mob. Under pressure, he was organising a plan to entrain two grenadier battalions to Hungary, from where there was more news of unrest. While one of these, the ‘Ferrari’ battalion, made up almost exclusively of Italians, marched off unmolested by the crowds, another, the ‘Richter’ battalion, found its way from its barracks in the Gumpendorferstrasse barred by a large mob.

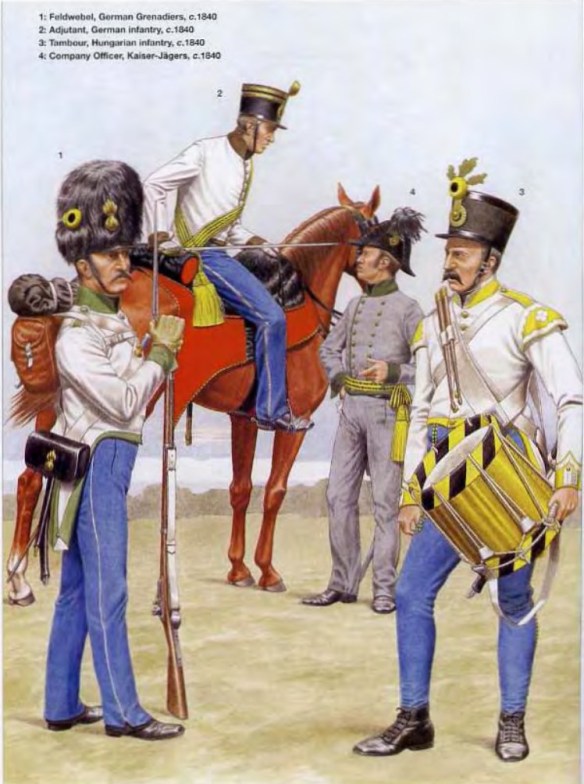

The ‘Richter’ battalion, like all grenadier formations, was made up of composite units. However, the demonstrating students soon realised that this battalion consisted of exclusively German-speaking regiments drawn from IR 14, 49 and 59, three Alpine regiments recruited from Lower Austria, Upper Austria and Salzburg. United by a common language, the grenadiers and the students began to fraternise, the latter offering the former beer and wine until discipline was restored by their officers, who cleared a way with the help of a cavalry escort for the battalion to march to the Nordbahnhof two miles to the east.

As the regiment neared the station, they saw that a huge crowd had sealed all the approaches to the Nordbahnhof. To avoid bloodshed, the order was given to march to Floridsdorf along the Danube and entrain there but the same mob followed and sealed off the grenadiers’ access to that station.

Latour over-reacts

When the news of these events reached Latour, the minister over-reacted and sent two squadrons of cavalry, some artillery and the entire infantry regiment ‘Herzog von Nassau’ (Nr 15) to drive the mob from the Floridsdorf station and the Tabor bridge, which they had closed to the grenadiers. This mixed force was commanded by Hugo von Bredy, a distinguished officer from a long line of Irishmen who had served the Habsburgs for generations. By the time they arrived, the grenadiers had completely lost discipline and were fraternising with the students. Incensed by this lack of military spirit, Bredy began to deploy his artillery, only to see the mob begin to cart his guns off. As this was happening, the officer ordered his infantry to open fire. The volley that crashed out killed a score of people but was returned with interest by the armed students, who fired into the densely packed infantry, inflicting more than a hundred casualties. Bredy went down with a bullet through his head and the colonel of the Nassau regiment fell from his horse in the hail of firing. The ‘Richter’ Grenadiers rushed to throw in their lot with the mob and from that moment their 800-strong force became the backbone of the rebellion in Vienna. They fought with enormous courage and heroism but their example was not followed in the rest of Austria. Spectacular and significant as their defection from the Imperial House was, they were the only Austrian military unit throughout the entire crisis of 1848 to mutiny. Every other unit of the Austrian army remained loyal to the dynasty.