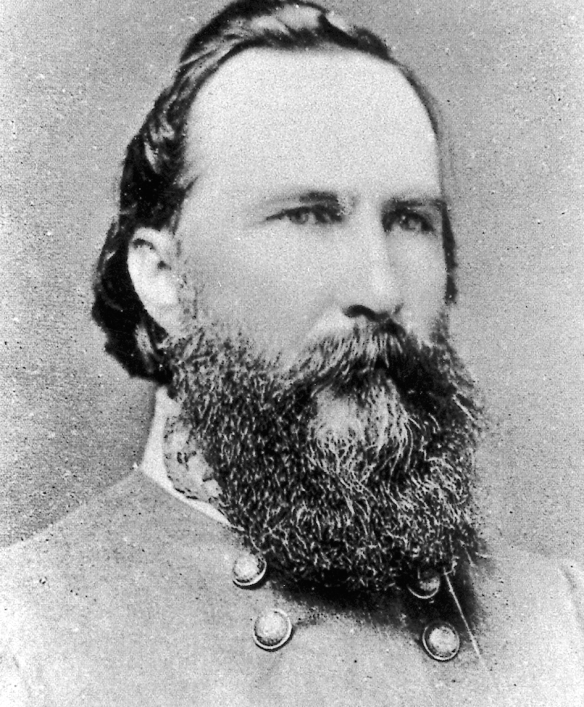

James Longstreet was of all Lee’s generals the least like what he appeared to be. There was nothing of Cassius’s “lean and hungry look” to hint at secret ambitions within the impassive Dutchman. A powerfully built man, deep in the chest, he glowed with the rugged health that suggested his pleasure in outdoor sports. A huge, bushy beard half-covered his stolid features, and clear blue eyes faced the world in aggressive self-assurance. On the surface, he appeared an uncomplicated physical type, and as such he was accepted then and has been historically.

Longstreet has been taken on his own evaluation. Studies have been based in general on acceptance of the substance of his many versions of his war career, though his accounts contains within themselves conspicuous inconsistencies and contradictions. Weighed against known facts, they contain gross inaccuracies Had he been a chronic failure and neurotic, like Braxton Bragg, the perversions of self-justification would have been expected; but hearty Longstreet, forthright and securely planted in a world of fighting men, boasted a superior combat record, a high reputation as a corps leader, and the confidence of General Lee. Then, the bitter, prolonged postwar arguments over Gettysburg tended to focus attention on his behavior in that battle, isolating this controversial action from his total record.

Far from being an isolated action of character, Longstreet’s conduct at Gettysburg was typical of episodes and events which, viewed in their entirety, formed a pattern of behavior totally at variance with the concept of the stolidly dependable “War Horse.” They reveal a Longstreet disturbed by ambitions beyond his limitations and confused, in his absence of self-knowledge, by his compulsion to present to the world the image of his self-evaluation.

The custom has been to pass over the separate incidents, some of which were explained away and others obscured by their historic insignificance. As early as the Battle of Seven Pines (May 31, 1862), there was criticism of Longstreet’s lack of cooperation, but the whole battle was bungled and the other generals involved faded from the scene. He was dangerously slow at Second Manassas, but criticisms were forgotten in the glow of final victory. In independent command, his futile siege of Suffolk (May, 1863) was overshadowed by the great victory of Lee and Jackson at Chancellorsville, and his gruesome failure at Knoxville was written off among the Western disasters in the winter of 1863-1864.

In personality difficulties, his earlier clash with A. P. Hill was explained by Hill’s emotionality, which led him also to clash with Jackson. Troubles with Hood and Toombs were blamed on these former subordinates. Longstreet’s current feuds, in May, 1864, with Lafayette McLaws and Evander Law, were waged through the war office and went largely unnoticed while all attention was focused on the gathering forces of the enemy. Besides, McLaws was a division commander of uninspiring competence and young Law was a bookish brigadier, and neither had strong supporters in the Army of Northern Virginia.

Yet Hill’s only two conflicts during the war occurred with Longstreet and Jackson, both of whom had long records of personality clashes. With Longstreet, Hill reacted to a spiteful gesture made by his then superior officer, when Longstreet grew resentful of a newspaper account which glorified Hill during the Seven Days.

With Law and McLaws, the War Department supported both against the persecutions instigated by Longstreet, and the ignored McLaws case was particularly revealing of Longstreet’s disturbance. In that, he falsely accused McLaws, as the subordinate, of precisely the same conduct of which Longstreet boasted in himself when he was Lee’s subordinate at Gettysburg.

Longstreet’s accusal of McLaws read: “You have exhibited a want of confidence in the efforts and plans which the commanding general has thought proper to adopt.” In writing about Gettysburg, Longstreet blamed Lee for not changing plans when he, the subordinate, showed his “want of confidence in them.” Lee knew, Longstreet wrote, “I did not believe in the attack.” Since Longstreet showed his opinion of such an attitude by using it in a trumped-up charge against the outraged McLaws, it would seem that he had not regarded himself as a subordinate at Gettysburg. Since that manifestly was his status, Longstreet was clearly a confused person beneath the exterior of bluff self-reliance.

His disturbance did not affect his considerable abilities in fighting and commanding troops at corps level, when he accepted corps command as his post. Beginning in the early winter of 1863, however, the good combat soldier was seized with ambitions for high command. As with many men overtaken by dreams beyond their limitations, he attributed to himself the necessary qualities. Not guileful by nature nor largely shrewd, his maneuvers for high command were clumsy. When he failed in his small independent venture during the winter of the Knoxville campaign, his goaded lunges at McLaws and Law, along with the dismissal of Dr. Jerome Robertson of Hood’s old brigade, brought him into the strong disfavor of the President and the war office. Then Longstreet blamed the administration for his troubles.

This personal record was not known in its entirety when Longstreet, having recently rejoined the army, met Lee and his fellow generals on Clark’s Mountain. Nor did anyone suspect that he had no liking whatsoever for the role of anybody’s “war horse.” Nothing in his personal history, as generally known, indicated either his ambitions or suggested his banked resentments of some of his brother officers.

Before the opportunities suddenly presented by the war, Longstreet probably had been the well-adapted extrovert which he appeared. Though born in South Carolina, he came of Dutch stock from New Jersey, moved early to the Lower South, and was not influenced by the strong place-identification of his fellows in the army. In the old army, as typical of all Southerners, his friendships had been formed non-sectionally on a basis of mutual tastes. Much could be learned about the personalities of Lee’s officers from the Northerners who had been their friends. A. P. Hill’s close friend, for instance, was brilliant, charming McClellan of privileged background; Longstreet’s was plain Sam Grant.

As captain in the old army, he transferred from the line to the paymaster department in order to achieve the higher rank and higher pay of major, saying he renounced all dreams of military glory. When he enlisted with the Confederate army, not with the troops of any state, he applied for a secure paymaster post. Having come to Richmond from a New Mexican garrison by way of Texas, he arrived later than most of the officers who came home from army posts, and appeared in the war office precisely when a brigadier was needed for three regiments of Virginia volunteers. By this circumstance, he began as a brigadier when his contemporaries were colonels and at promotion time went to major general when they made brigadier.

When Lee emerged into power and formed the loose hodgepodge of units into two corps of four divisions each, Longstreet was given the First Corps both by seniority and on performance. Jackson’s rise to Second Corps command from colonel was more meteoric, and his brilliance caught the imagination of the world as well as the South. Nobody suspected Longstreet’s jealousy of Jackson’s wider fame. While the army and the public held Old Pete in deep regard as Lee’s “War Horse,” prudent Longstreet suffered a middle-life resurgence of lust for glory.

It is possible he was influenced by the rise of his friend Grant, a man of his own type, whose similar traits of stubborn tenacity had carried him by 1863 to army command. Also Grant operated in the West where, with competition thinner among gifted leaders, the opportunities to shine were greater. Early in 1863, Longstreet began to maneuver to remove his corps from Lee’s army, where he was overshadowed by Stonewall Jackson.

It was when detached from Lee, and trying to effect a transfer of his corps to the poorly commanded Confederate Army of Tennessee, that he failed in the pointless siege of Suffolk, while the army was winning its greatest victory at Chancellorsville. Then Jackson’s death in May, 1863, removed his rival from the Army of Northern Virginia, and Longstreet returned to Lee with the undeclared purpose of replacing Jackson as Lee’s collaborative right hand. What Longstreet failed to perceive was that Lee and Stonewall had held similar concepts of war, of the strategy for implementing it and of the tactics for executing the strategy. With nothing too audacious for Old Jack, Lee had employed Jackson’s mobile striking force for the bolder aspects of his strategy. With Longstreet defense-minded and methodical, Lee had employed his dependables for the orthodox work.

The misunderstanding in the Gettysburg campaign arose when Longstreet, in the thrall of his ambitions, presumed the collaborative partnership with Lee and sought to impose on the commanding general his defense preferences. In seeking the glory, he lost a sense of reality. His mind dominated by a determination to fight a battle under conditions which gave opportunity to his special gifts, the corps commander ceased to react responsibly to the actual conditions on the field. Afterwards Longstreet was never clear about what happened. In some twisted self-justification he opened the Gettysburg issue in a period of bitter feeling between himself and his comrades. The trouble really began when security-minded Longstreet accepted a Federal job in New Orleans from his friend, then President Grant, and of necessity became allied with the Reconstruction occupation government against former Confederates.

Although there is even argument about who started the argument, the first public criticisms of Longstreet came in answer to a letter he allowed to be circulated. Then Longstreet publicly justified his Gettysburg behavior by denigrating Lee, shortly after his death. Already regarded as an apostate, Longstreet brought down on his head the outraged fury of Lee’s veterans, a number of whom had apparently been doing some brooding over Gettysburg.

The curious feature of the controversy was that the charges and countercharges ignored what Longstreet actually did to contribute to the Confederate failure in the battle. The arguments centered chiefly on Longstreet’s slowness, which was involved in an alleged conflict with Lee over strategy. He undeniably delayed going into action in a sullen spirit observed by many, but this deliberate procrastination was a symptom of his disturbed state and not in itself a decisive factor in the battle.

In the controversy over this red herring, Longstreet justified his slowness on the grounds that he opposed Lee’s plans and procrastinated in order to persuade the commanding general to follow his, the subordinate’s, superior strategy. In contradictory accounts, Longstreet wrote some highly dramatic scenes describing arguments with General Lee that seem, at best, improbable.

Considering that the accounts were written after Lee’s death, and not one witness of that thoroughly reported battle ever referred to the high-flown dialogue which Longstreet attributed to himself, it is amazing that Longstreet’s conflicting versions were ever studied seriously. His after-the-fact rationale of the strategy he claimed to have presented is so at variance with the facts of his erratic behavior that most likely little of his drama with Lee ever happened.

What did happen was glossed over by Longstreet and has been strangely ignored. Four generals and one colonel of his corps, each writing independently of the others and none involved in the controversy, gave a composite account which traced those irrational actions of Longstreet that did seriously affect the outcome of the second day’s battle. In a mutinous mood which made him scarcely responsible, he insisted on his subordinates’ obeying an old order of Lee’s after Longstreet perceived the conditions on the field to be different from the conditions presumed in the order. Except for the refusal of subordinates (particularly Brigadier General Evander Law) to follow his senseless command, Longstreet would have committed two divisions to mass suicide. As it was, he directed one of the most disjointed, ill-managed assaults in the war.

Lee never knew the details of Longstreet’s mutinous bungling on the second day and Longstreet never appeared to remember it. Perhaps his memory drew a curtain over the details. Evidently he did recognize that he was not to be Lee’s collaborator and replace Jackson, for immediately after the battle Longstreet reverted to the West as the more fertile field for advancement. At Chickamauga, in command of an army wing under Braxton Bragg, he performed at his battlefield best. However, the field victory was negated by Bragg’s neurotic ineptitude. Longstreet, instead of finding opportunity, found himself in a disastrous command situation which, he wrote, “called for some such great mind as Lee’s.” Partly to resolve his difficulties with Bragg, Longstreet was given the independent assignment of the siege of Knoxville. Of this Mrs. Chesnut, the outspoken diarist, recorded: “Away from Lee, what a colossal failure is Longstreet.”

It was in trying to avoid this verdict and the consequences that Longstreet became embroiled with subordinates, particularly Major General McLaws and Evander Law, and with maladroit stubbornness tried to impose his will on the President and the War Department. By then the spring campaign was approaching and Lee wanted him back. In a final floundering to retain independent command, Longstreet became suddenly offense-minded and turned to vaporous schemes for taking the war to the enemy.

It was a time when many Confederate leaders, despairing of their fortunes under the existing policies, began to clamor somewhat unpractically for counteroffensives. Joining this trend, Longstreet not only abandoned his orthodoxy but also those rudiments of supply and logistics about which, at corps command, he was most meticulous. Before the President decided that Longstreet must return to Lee’s army, and while his two divisions were being considered for various of the fanciful strategies then in the air, Longstreet sent the war office a plan which read like the daydream of an amateur Napoleon.

As by then Longstreet enjoyed no friends at court, his suggestions were dismissed with no regard for his feelings. Having grown understandably touchy himself, Longstreet became convinced that, as he phrased it in quotation marks, the “authorities at Richmond” had it in for him. The effect of the administration’s rejection of his last desperate effort toward independent command was to turn Longstreet to Lee as his one friend. A thoroughly bewildered Cassius, Old Pete was at last willing to return to his familiar role of Lee’s “War Horse.”

It is significant that Longstreet’s Tennessee campaign was extremely important to him. In the book he wrote thirty years after the war, he devoted more attention to his independent command than to any other aspect of the war. The lack of interest inherent in an abortive secondary campaign, along with the obscuring effects of the Gettysburg controversy, caused this phase of Longstreet’s war career to be ignored. If his failure in the West is viewed in the significance which it occupied in Longstreet’s mind, his attitude to the war-horse role becomes clearer.

He returned to Lee’s army when no other avenues of advancement were open to him, but all evidence indicated that he returned more in a spirit of relief than of reluctance. Whatever of his ambitions may have lingered, he was at last back on familiar ground, where he was welcomed and respected. There was another thing too. A devoted Confederate and a practical man, Longstreet recognized that the South’s chance of independence and his family’s future resided largely in the ragged forces fielded by Lee.

It is likely that the outwardly stolid Dutchman was in a sounder mental attitude when he took his place among the other generals on Clark’s Mountain than he had been since his aspirations began to disturb him in the winter of the year before. Though no one could presume to know his exact state of mind, General Longstreet at least appeared the dependable subordinate of the good days of the army. Certainly General Lee accepted him as such.