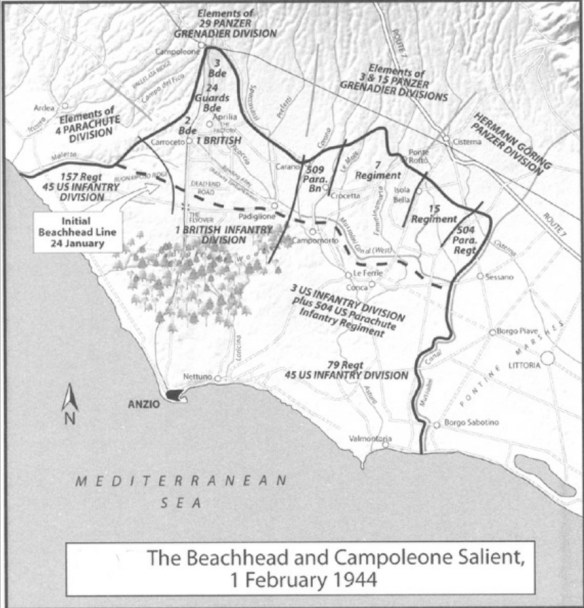

Amongst the new arrivals had been the 45th US Infantry Division commanded by Major General William W. Eagles, and 1st US Armored Division commanded by Major General Ernest N. Harmon. Eagles according to Lucas, was a ‘quiet, determined soldier, with broad experience’ whilst Harmon, although also determined and experienced, was far from quiet. Born into poverty in New England and orphaned at the age of ten, this ambitious character was the embodiment of the American Dream. Now in his fiftieth year, Ernest Harmon was a bull of a man who sported two pearl handled revolvers. He lacked tact, but demanded respect, and had been carved from the same granite as Patton. It was without any sense of irony, however, that Lucas welcomed Harmon to the beachhead with the words, ‘Glad to see you. You’re needed here.’ His Combat Command A was just in time for the attack on the night of 28 January and was to support 1st Division’s attack towards Campoleone. On 27 January the Scots Guards had pushed on from the Factory and taken what the officers called ‘Dung Farm’ and the men called something else on account of the smell of rotting animals and manure. From this foul place the Scots were to secure a road between the farm and Campoleone, with the Grenadier Guards attacking on their left. Once this road had been taken 3rd Brigade were to launch an assault to Campoleone Station. Combat Command A was to support the attack by swinging across the Vallelata Ridge west of the Via Anziate and south west of the station. In a secondary but simultaneous attack, two battalions of Ranger Force were to infiltrate Cisterna during the night whilst its third cleared the Conca—Cisterna road in preparation for the main onslaught on the town by 15th Infantry Regiment the following morning. Subsidiary attacks by 7th Infantry Regiment and a company of 30th Infantry Regiment on the left to cut Route 7 north of Cisterna, and 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment on the right were to further occupy the enemy defences. If Lucas’s offensive was successful then Tenth Army would, at last, feel the impact of Operation Shingle. By the end of January with 34th Division having managed to create a small bridgehead over the Rapido, and the French 3rd Algerian Division threatening in the hills to the north, Alexander was sensing a breakthrough. By reinforcing Clark with the New Zealand Corps and co-ordinating an attack on the Gustav Line to coincide with the attacks at Anzio, the Fifteenth Army Group commander still hoped to force Kesselring into a withdrawal.

With Clark rubbing in the need for immediate offensive action to Lucas at their meeting on 28 January, it was extremely unfortunate that, even as he spoke, an incident took place in the beachhead which was to lead to the postponing of the attack. That afternoon a party of eight Grenadier officers and three other ranks were driving up the Via Anziate to Dung Farm for an Order Group prior to their attack. Missing the turning to the farm their jeeps had continued up the main road and run into automatic fire and hand grenades from a German outpost. Three officers and a Guardsman were killed, one officer and two Guardsmen wounded and taken prisoner. The four officers that escaped did so courtesy of an incompetent German machine gunner and the pall of smoke that blew across the road from a burning jeep. As a result of the episode both 1st and 3rd Division attacks were postponed for twenty-four hours and the Irish Guards had taken the place of the devastated Grenadiers on the left of the attack. The postponement had been no mere inconvenience. On 29 January another 17,000 German troops arrived taking their total to 71,500 men. Amongst them were 7,000 soldiers from the 26th Panzer Division that reinforced Cisterna.

As von Mackensen’s defences absorbed the newly arrived troops on 29 January, 1st and 3rd Divisions were making the final adjustments for their postponed attack. The weather was atrocious causing Combat Command A to slip and slide their way through difficult country to their jumping off point. Their problems were exacerbated when a German artillery observer spotted their laboured movements, calling down a bombardment. Harmon’s preparations were ruined, the deployment took far longer than he anticipated and continued long after darkness had fallen. There was no reconnaissance, orders were rushed and the whole experience had been thoroughly miserable. To make matters worse a British officer from 2nd Brigade was captured with a set of 1st Division plans after he had got lost and wandered into the German lines. It was a very tense time. Across VI Corps there was at last a feeling that something positive was being done to push forward, but there were also concerns that it had been left too late and the enemy would be waiting for them in numbers. One platoon commander in the Guards Brigade remembers his company commander being uncharacteristically anxious:

He had already been through a great deal during the war, and the constant bombarding that we were suffering played on his nerves. He seemed to tremble, and had definitely developed a stammer, but he got on with his job and ignored it, and so did we. We were all on the edge and knew that it could happen to any one of us at any moment… As I left he put his hand on my shoulder and asked how my feet were -1 had some blisters caused by some new boots – and he gave me a knowing smile saying that I could wear them in by giving Jerry ‘a jolly good kick up the arse’. That evening I made sure that I stayed with the men for as long as possible. They were all nervous and needed reassuring. Some needed a reassuring word, others just a wink, or a smile. I was new to this leadership lark, but I seemed to feel what they needed, and was well aware that I could very well provide the last kindness of their lives. It struck me then that leadership is not about shouting and screaming, it is about empathising, understanding, and motivating – just as my company commander had cleverly done when asking about my rotten boots.

Captain David Williams, a British staff officer in the 1st Division headquarters in the Padiglione Woods, began to feel tense. It had been ‘an exciting, but draining experience’:

My job was to summarise the intelligence that was coming into the headquarters and put it in a report. Although I was not responsible for the quality of the information that I was working with, I still felt a massive weight of responsibility on my shoulders as I had to interpret it . . . Everybody got quite short with each other during 29 January. They were tired, over-worked and under a great deal of strain. We were also working in quite cramped conditions in tents that leaked and were cold. I can remember feeling quite faint during that day and could not understand why. Then it dawned on me. I had not had a meal for nearly 24 hours. I grabbed a ration pack and carried on . . . The worst moment came that night, once the attack had been launched, waiting for the first word on progress – or the lack of it. We had been taught no plan survives the first contact with the enemy. I could not get that out of my head.

At 2300 hours, the Irish and Scots Guards advanced behind a ferocious creeping barrage. The aim was to keep the enemy’s heads down long enough for the infantry to pounce on them unchallenged. A mixture of the dark, smoke and battlefield debris, however, combined to slow the two battalions and they fell quickly behind the protective wall. The attack covered half a mile before the Germans illuminated the battlefield with flares and Very lights. Small groups of Guardsmen could be seen scuttling along in the slowly falling light, to be cut down by German machine gunners. An NCO shouted an order whilst silhouetted by burning scrub and he too was poleaxed. The battalions had walked into a killing bowl. Mesmeric tracers hissed, supply vehicles exploded turning their drivers into charred mummies, shells burst spraying deadly fragments into soft bodies and the wounded screamed. The platoons made an attempt to reach the enemy that were firing from all around them, but the attack quickly became fragmented. The officers tried to bring order to the chaos, but often became casualties themselves whilst leading their men in the face of the German guns. The two commanding officers, Lieutenant Colonel C.A. Montagu-Douglas-Scott of the Irish Guards and Lieutenant Colonel David Wedderburn of the Scots Guards, were both at Dung Farm trying to control the battle through radio links with the companies, but they had difficulty trying to work out what was happening as shells began to tear their headquarters to pieces. The two battalions staggered forward in small unit actions, firing and manoeuvring. It was a messy battle, as one Guardsman recalls:

Such a lack of information, and no cover in those vines. Shells screaming and whirring like mad, vicious witches. Sprays of fire all over the place. Shrapnel like hail. Bullets whizzing from nowhere. And on top of that the bloody rain. We were so cold. Half the soldiers disappeared – mown down, captured, or just fucked off, everything you can imagine.

Gradually the Guards managed to get close enough to their enemy to use their bayonets and grenades in vicious hand-to-hand fighting, but by midnight they only had a tenuous hold on the lateral road either side of the Via Anziate. Digging in as best they could, they managed to hold on to their positions for the rest of the night, but with dawn threatening, armoured support was required if they were not to be overwhelmed. Brigadier Alistair Murray promised tanks to the Scots Guards advising them by radio, Tm going to send up our heavy friends to see what they can do. Stand by!’, but just five Shermans arrived from a weakened 46th Royal Tank Regiment, and there were none for the Irish Guards. One Irish Guardsman wrote that he had been trying to dig a shell scrape for hours to give himself a precious few inches of protection, but mortars and shells constandy interrupted his work. ‘The most frightening moment came just before dawn’, he recalls, ‘when a ruddy great Tiger tank appeared about 150 yards in front of me. We had no weapons to attack it with and so I prayed that the thing would go away and it did. It clanked across the field and disappeared. Some other poor sod had to deal with it.’ Two Tiger tanks engaged the Irish Guards and the situation was becoming critical for them, but just when they needed guidance from battalion headquarters most, radio communication was lost. Radio operator Lance Corporal G. Holwell dismantled his 18 set to try and solve the problem, laying out a plethora of fragile pieces on a ground sheet. Using the thin beam of a shaded torch which attracted fire, he reassembled them and got the radio working again just in time to receive the order to withdraw at 0615 hours. The remnants of the battalion pulled back down the railway line but Holwell was not amongst them, a shell fragment having killed him.

Penney had to strike back at Campoleone quickly, for by dawn on 30 January the Scots Guards were firm but vulnerable around the lateral road. At 0900 the artillery threw down another bombardment and the Irish Guards, supported by a company of King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, again attacked. They pushed through a scene of devastation—smouldering vehicles, destroyed buildings, the wounded crying for help and the dead. The air was acrid with smoke and the smell of cordite. The renewed effort linked up with the Scots Guards and the five Shermans supporting them and together they clattered into the German defences. It was enough to dislodge the tired defenders who retreated back to the embankment below Campoleone Station. The British needed to maintain their momentum and so at 1500 hours 3rd Brigade leapfrogged the exhausted Guards and struck towards the embankment – 1st Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (Dukes) on the left and the 1st King’s Shropshire Light Infantry Regiment (KSLI) on the right. The men screamed and shouted at the enemy as they attacked to give themselves courage, but many fell trying to cross the open ground. Sergeant Ben Wallis recalls the moment when he attacked:

I had never been so frightened. We were all frightened, don’t believe anybody that says he wasn’t. We’d heard the fighting earlier in the day, seen the dead and dying—now it was our turn. I turned to my mate before the off and we shook hands. The order was given to advance, and we walked into bullets, mortar bombs and shells. They were waiting for us, we didn’t stand a chance. My mate, Billy, was killed by a sniper. I was shot through the shoulder and evacuated out. I was lucky as I later heard that out of our platoon – which was about 35 men – only 10 survived.

After two hours the KSLI and Dukes were still short of the embankment. Exposed and vulnerable at the end of a long salient, the battalions did what they could in the growing darkness to dig in. That night 3rd Brigade continued to suffer casualties as Private David Hardy of the Dukes explains:

We were shelled and mortared throughout the hours of darkness, unable to move. I was in a shell hole with another bloke which we managed to deepen a little. Others were in far worse positions and had no real protection. The lads on our left and our right copped it that night.

When one Dukes officer who was contacted on the radio by brigade headquarters and asked about their situation replied, We feel like the lead in the end of a blunt pencil’, he was told not to fret because the armour would force its way through with the next drive forward. The officer was not impressed and said, ‘The bastards said that they would be here today, but I’ve seen nothing of them.’

The attacks that day would have been assisted by strong armoured support, but Harmon made no impact on the battle. Having struggled to get his tanks to the start line immediately prior to the attack on the 29th, he did not begin his advance until seven hours after the infantry. When the tanks, tank destroyers and half-tracks eventually began to move, they were again held up by the terrain and picked off by German anti-tank guns on the Vallelata Ridge directly in front of them. It was a natural tank trap. A number got stranded in irrigation ditches. Harmon tried to help, but only succeeded in diluting his resources:

I ordered an armored wrecker to pull them out. The wrecker was ambushed by the Germans. I sent four more tanks to rescue the wrecker. Then I sent out more tanks after them. Apparently I could learn my first Anzio lesson only the hard way – and the lesson, subsequently very important, was not to send good money after bad. Because I was stubborn, I lost twenty-four tanks while trying to succour four.

Battle-scarred main road from Anzio to Rome littered with wrecked Allied armor, including an M10 tank destroyer (left) and Sherman M4 tanks — a result of battle between German and Allied forces fighting for control of the Anzio beachhead area, 1944.

One by one the stranded vehicles were destroyed and evacuating crews cruelly picked off by snipers. Harmon’s attack had failed even before it had got going:

Half of me was seething and the other half was shattered. When I moved up to the front line at 8 o’clock that morning, nothing was moving and I was greeted not by rapidly moving armoured fighting vehicles, but by their smouldering wrecks and scores of dead and wounded.

On hearing that Harmon had called off his attack Penney immediately radioed him and said: ‘Would you mind putting some of your tanks on to the Campoleone road so that they might help out my 3rd Brigade in the morning?’ The 1st Armored Commander replied: ‘Show me the way!’, and that night moved 25 light tanks onto the Via Anziate to assist with the attack on Campoleone Station the following morning.

The renewed thrust began at dawn on 31 January, when the 3rd Brigade’s reserve battalion, 2nd Sherwood Foresters Regiment (Foresters), supported by Penney’s tanks, pushed through the Dukes and KSLI and endeavoured to get to the railway embankment. Wynford Vaughan-Thomas watched the attack from the north of Dung Farm:

All we could see were the quick fountains of black smoke thrown up along the railway line, a tank belching fumes from behind the walls of a broken farm and a cloud of white dust hanging over the spot where we imagined the station to be. The Alban Hills seemed startlingly near. The noise ebbed and flowed over the leafless vines, now rising to a general thunder as the guns cracked out on both sides, now dropping to a treacherous lull. Small figures now appeared, popping up from holes in the ground and half crouching they ran. There seemed so few of them . . . We saw them drop out of sight and heard the swift outburst of the machine-gun fire that welcomed them. Were they over the railway line? Was Campoleone ours?

Campoleone was not theirs. The Germans had been reinforced overnight with two extra battalions of infantry, six Mark IV tanks and three 88-mm guns and defended stubbornly. When the attack was put in it was immediately devastated. In just ten minutes 265 Foresters became casualties along with fourteen tanks. Some managed to get to the embankment, but no further. One of the battalion signallers, Sergeant Thomas Middleton, got separated from his colleagues during the attack:

I was alone in my lonely world . . . The noise of the place was incredible, the smell was foul and I could hardly think straight. I moved forward half crouching, half stumbling, I was totally disorientated. I came across one of our boys locked in an embrace with a German, hit by shells whilst grappling with each other. Their entrails smothered the ground. The knowledge that the Germans were in the area put me in a spin. Was I moving towards them or they towards me? Where was the headquarters? I tried to raise someone on the radio but could not hear anything as shells landed around me. I may have been wandering for 5 minutes or 2 hours, I do not know, but I finally found myself back with the battalion. I was told to take up a defensive position and only then did I realise that I had been wandering around without having touched my Sten gun which was still slung over my shoulder.

The remnants of the battalion pulled back, reorganised, and another attempt was made to burst through, but with the same predictable results. The American tank crews were amazed at the stoicism of the British troops. Kenneth Hurley, a loader, later wrote:

From that day on I vowed never to knock the Limeys again, bless their black hearts. The British went on and on, with just their courage, soup bowl helmets and rifles for protection. Crazy, but brave like I’d never seen. ‘Give it up won’t you?’, I thought, ‘for God’s sake don’t try again!’ But they did. A British officer was walking between the tanks, crying out something to his men huddled around. I wanted to shout, ‘You silly bastards, get down!’ It was a different concept, a different attitude. The British lieutenant strolled across the front of my tank, bobbed down out of sight, then waved his swagger stick. They charged, about 20 of them. None returned.

The Sherwood Foresters did not give up and attempt after attempt was made to cross the embankment, but the men just melted away. A desolate Harmon visited the battlefield that morning and later wrote:

There were dead bodies everywhere. I had never seen so many dead men in one place. They lay so close together that I had to step with care. I shouted for the commanding officer. From a foxhole there arose a mud-covered corporal with a handle-bar moustache. He was the highest-ranking officer still alive. He stood stiffly to attention. ‘How’s it going?’ I asked. Well, sir,’ the corporal said, ‘there were a hundred and sixteen of us in our company when we first came up, and there are sixteen of us left. We’re ordered to hold out until sundown, and I think, with a little good fortune, we can manage to do so.’

But the battle did not last until sundown; Penney brought it to a close on Lucas’s orders in the early afternoon. The Sherwood Foresters had started out as 35 officers and 786 other ranks and ended the day with 8 officers and 250 other ranks. The battle had come to a halt on the body-littered embankment before Campoleone. The British attempt to threaten the Alban Hills from the Via Anziate had failed.

Lucas also had to cope with his failure. Campoleone and Cisterna were still in German hands. Both Alexander and Clark were unhappy. There would not now be a push to the Alban Hills and the Gustav Line continued to be supplied. The Fifth Army commander arrived in the beachhead on 30 January and went immediately to his newly established forward headquarters in the grounds of Prince Borghese’s Renaissance palace between Anzio and Nettuno. Lucas was dispirited: ‘Clark is up here and I am afraid intends to stay for several days. His gloomy attitude is certainly bad for me … I have done what I was ordered to do, desperate though it was. I can win if I am let alone but I don’t know whether I can stand the strain of having so many people looking over my shoulder.’ During an edgy meeting the following day, Clark heavily criticised Penney, Truscott and Darby for their plans. Once Clark’s rant was over, Lucas stepped forward and announced that, as corps commander, he had sanctioned the divisional plans and should take any blame for their failure. Ignoring Lucas’s noble gesture, Clark launched into another stinging attack on Darby and Truscott for the way in which they had used the Rangers. It was Truscott’s turn to put up a defence and he replied that as he had been responsible for organising the original Ranger battalion, and that Darby had commanded them through so many battles, nobody understood their capabilities better. Mark Clark turned mutely on his heel and departed, leaving a bitter atmosphere hanging in the air. That evening Lucas wrote:

I don’t blame him for being terribly disappointed. He and those above him thought this landing would shake the Cassino line loose at once but they had no right to think that, because the German is strong in Italy and will give up no ground if he can help it. . . The disasters of the Rangers he apparently blames on Lucian Truscott. He says they were used foolishly … Neither I nor Truscott knew of the organized defensive position they would run into. I told Clark the fault was mine as I had seen the plan of attack and had OK’d it.

Clark, meanwhile, noted:

I have been disappointed for several days by the lack of aggressiveness on the part of the VI Corps. Although it would have been wrong, in my opinion, to attack to capture our final objective on this front, reconnaissance in force with tanks should have been more aggressive to capture Cisterna and Campoleone. Repeatedly I have told Lucas to push vigorously to get those local objectives. He had not insisted on this with the Division Commanders … I have been harsh with Lucas today, much to my regret, but in an effort to energize him to greater effort.

The failure of Lucas’s offensive sent shock waves back to London. On 1 February Alan Brooke wrote despondendy: ‘News from Italy bad and the landing south of Rome is making little progress, mainly due to the lack of initiative in the early stages. I am at present rather doubtful as to how we are to disentangle the situation. Hitler has reacted very strongly and is sending reinforcements fast.’ On the same day Churchill wrote to Alexander: ‘It seems to have been a bad show. Penney and Truscott seem to have done admirably considering what they were facing. Does Lucas have any idea what a mistake he has made?’ There was a very strong feeling now that Lucas had waited far too long to make this push and numerous opportunities had been missed. The VI Corps commander knew that his bosses were frustrated and when Alexander visited him in the beachhead on 1 February, Lucas feared for his command. Lucas recalled that Alexander had been:

. . . kind enough but I am afraid he is not pleased. My head will probably fall in the basket but I have done my best. There were just too many Germans here for me to lick and they could build up faster than I could. As I told Clark yesterday, I was sent on a desperate mission, one where the odds were greatly against success, and I went without saying anything because I was given an order and my opinion was not asked. The condition in which I find myself is much better than I ever anticipated or had any right to expect.

The ‘condition’ in which VI Corps now found itself was having to defend. In a move agreed by Alexander and Clark, Lucas ordered that the new enlarged beachhead should be defended and a ‘final’ defensive position should be developed on the line of the original 24 January beachhead.

By the first days of February, Operation Shingle was foundering. Rather than having the strategic impact that Churchill and Alexander had desired, the two men were left to ponder two vulnerable salients, a narrow British one towards Campoleone and a wider American one towards Cisterna. VI Corps was worse off than before Lucas’s attacks had started. The correspondents sought enlightenment at Lucas’s villa in Nettuno. ‘He sat in his chair’, wrote Wynford Vaughan-Thomas, ‘before the fire, and the light shone on his polished cavalry boots. He had the round face and the greying moustache of a kindly country solicitor. His voice was low and hardly reached the outer circle of the waiting Pressmen. They fired their questions at him, above all Question No 1, “What was our plan on landing and what had happened to it now?” The General looked thoughtful. “Well gendemen, there was some suggestion that we should aim at getting to those hills” – he turned to his G-2 – “What’s the name of them, Joe? But the enemy was now strong, far stronger than we had thought.” There was a long pause, and the firelight played on the waiting audience and flickered up to the dark ceiling. Then the General added quietly, “I’ll tell you what, gendemen. That German is a mighty tough fighter. Yes, a mighty tough fighter.’”

So ended the first phase of the Battle of Anzio. The next phase was to be even more violent, and to introduce it the Germans would launch a series of counter-attacks. The pallid and quiedy spoken Gruenther said of the Germans, ‘You push the accordion a certain distance and it’ll spring back and smack you in the puss. The Germans are building up a lot of spring.’ The enemy now had the initiative. Private James Anderson, a replacement for 30th Infantry Regiment, arrived at Anzio harbour on 1 February as it was under air and artillery fire. ‘I remember plainly’, he recalls, ‘a British officer screaming at us, “What’s the matter with you blokes, do you want to live forever?’”