by Generalleutnant Karl Wilhelm von Schlieben

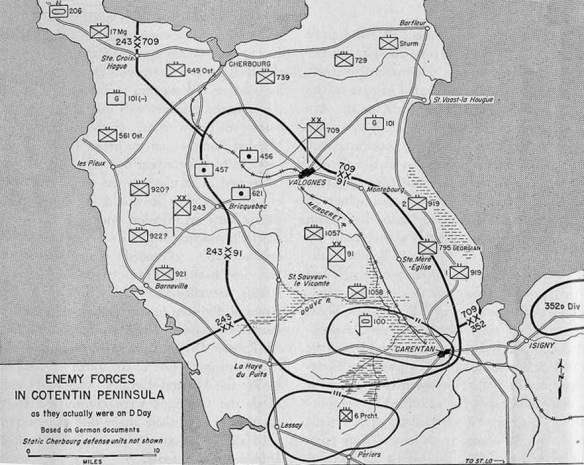

On the evening of 6 June I reported by telephone to the Commanding General, General der Artillerie Marcks, on the development of the situation with regard to the 1058th Grenadier Regiment and my plans and preparation for 7 June. The Commanding General expressed his approval, particularly of my intention to increase the fighting power of the regiment by the assignment of the two motorized artillery battalions and the self-propelled gun company of the 709th Light Battalion. Into the evening of 6 June I learned that the commander of the 922nd Grenadier Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Müller, who had been assigned to the 243rd Division on the west coast, had been transferred by the “Senior Officer of the Garrison on the Cotentin Peninsula,” Generalleutnant Hellmich, with regimental troops of the 922nd Grenadier Regiment, the 3rd Battalion 922nd Grenadier Regiment, one battalion of the 920th Grenadier Regiment, and the engineer battalion of the 243rd Infantry Division, to Montebourg by night-march (night of 6–7 June). The regiment was to advance south with its left wing along the St-Floxel–Fontenay-sur-Mer–Ravenoville road. I do not remember what its mission was. I presume it was to prevent a widening of the enemy bridgehead to the north and to support the left flank of the 1058th Grenadier Regiment.

I also had moved the 3rd Battalion of the 729th Grenadier Regiment, commanded by Major der Reserve Elbrecht, who was killed in action later on, from the area of Height 180.2 southwest of Cherbourg to the area east of Montebourg.

Generalleutnant Hellmich also dispatched the 3rd Battalion of the 243rd Artillery Regiment (less the 10th Battery) from the west coast via Bricquebec to Valognes. The two batteries took up position during the fight of 6 June near Écausseville (3½ kilometers south of Montebourg). They were assigned to Regimental Staff Seidel and supported the attack of the 1058th Grenadier Regiment on 7 June.

In the night of 5 June the Seventh Army assault battalion was placed into such a difficult position by an encircling movement that its commander decided to withdraw west to the Montebourg–Neuville-au-Plain road. There the battalion supported the 1058th Grenadier Regiment, which throughout that day had fought with varying success to capture Ste-Mère-Église.

On this day a number of enemy tanks made their appearance. The fire of large-caliber enemy naval guns and strong mortar fire added further to our discomfort. The heavy fire of the naval guns also prevented an attack by Regiment Müller (3rd Battalion 922nd Regiment, 1st Battalion 920th Regiment), which had been tired by its night-march, from making progress.

In the afternoon of 7 June, at a location north of Neuville-au-Plain, I gained the impression that the 1058th Regiment was no longer even able to capture Ste-Mère-Église, much less hold it against the fire of the enemy naval guns and tanks. The AT Battalion of the 709th Division had suffered considerable losses, but on the other hand had achieved good results. Enemy tanks fired from Neuville at the highway leading to Montebourg. Together with retreating units of the 1058th Regiment, men of the Seventh Army assault battalion and artillerymen of the 3rd Battalion 243rd Artillery Regiment, I succeeded in stopping the beginning of a panic caused by the enemy armor and to establish a makeshift defense line on both sides of the Montebourg–Ste-Mère-Église high road, 1,200 meters to the north of Neuville-au-Plain. It lacked, however, any antitank defense.

During the afternoon of 7 June I clearly saw that the enemy beachhead could no longer be eradicated by counterattacks of local reserves. This would require an organized attack with strong artillery support and a Panzer formation, and for this purpose the strong enemy air forces and naval guns would have to be neutralized. But the enemy air forces and navy were entirely unopposed. Neither our own Luftwaffe nor Navy rendered any assistance.

Therefore I decided to assume the defensive, and try to prevent the enemy from breaking out of his beachhead in a northerly or northwesterly direction. My impression, which was that the enemy intended to advance quickly north from his beachhead at Ste-Mère-Église and try to capture Cherbourg, proved later on to be correct. On 6 June an operational order of the American VII Corps was washed ashore. In substance the order said that the US VII Corps with four divisions (of which two airborne divisions were in the first wave) had the mission of turning to the north from the Quineville–Carentan beachhead, which was protected on the south, and of taking Cherbourg from the landward side while … At that time I hoped that Panzer Group West, which had been mentioned in orders before the invasion, could appear supported by 1,000 German fighter planes (this figure had actually been given me before the invasion) in order to stamp out the enemy beachhead.

I organized a task force under Colonel Rohrbach, the commander of the 729th Grenadier Regiment. I did not assign this task to the commander of the 919th Grenadier Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Keil, who was closer, as at that time I expected further landings between Quineville and St-Vaast-la-Hougue. Nevertheless I took away his third battalion, assigning it to Colonel Rohrbach, to whom furthermore the 100th Smoke Battalion (less one battery), which was employed at Morsalines with the beach as its field of fire, was attached.

In the evening of 7 June there was a makeshift defense line on the Montebourg–Ste-Mère-Église road, 1,200 meters north of Neuville-au-Plain and on the Fontenay-sur-Mer–Ravenoville road, without support on either flank. The 1058th Grenadier Regiment had suffered badly and was in a confused condition. Its commander, Colonel Beigang, was and remained missing.

At this time the absence of a corps headquarters staff near the front was badly felt. The divisions received little orientation on the major situation. It was difficult to get in touch by telephone with LXXXIV Corps headquarters at St-Lô. The distance was 60 kilometers and the enemy was in between. On the evening of 7 June I decided to weaken the garrisions of the bases and islands of resistance of the seafront, which had not been attacked, and to leave only emergency garrisons there. Such a measure had been provided prior to the invasion by a printed directive. When the catchword “emergency garrison” was given, only a few men remained at the bases and islands of resistance, whereas all the others assembled inland in reserve.

In this connection the complete lack of mobility of the stationary infantry divisions was particularly unpleasant. Men who had been assigned to the northeast coast had to walk more than 30 kilometers to reach the area south of Montebourg. Supplying them became a problem, as each company had only horses for its field kitchen, which, however, had to feed the emergency garrisons remaining at the bases.

Although the daily reports of higher headquarters mention fighting by the 709th Infantry Division at Montebourg, it must be made clear that during the first days after the enemy landing the bulk of the division was tied to its bases and islands of resistance along the coast from the mouth of the Vire river half way to Cherbourg–Cap de la Hague. The bringing up of the men from the bases and islands of resistance, which had not been attacked, was made more difficult still because the enemy air forces completely patrolled the high roads and fired unopposed at the smallest formations. Not even single men or cyclists could move freely on the road in broad daylight. I myself was fired on on 9 June by two P-47 fighter-bombers at a few seconds’ intervals when driving to a troop unit. My car was burned and I had to walk several kilometers. In this way the enemy air surveillance was a great handicap to the German commanders and their troops. Even if a motor vehicle was not hit, it was not possible to drive straight to the destination in broad daylight, as again and again the car had to be stopped and the personnel take cover quickly when enemy fliers attacked.