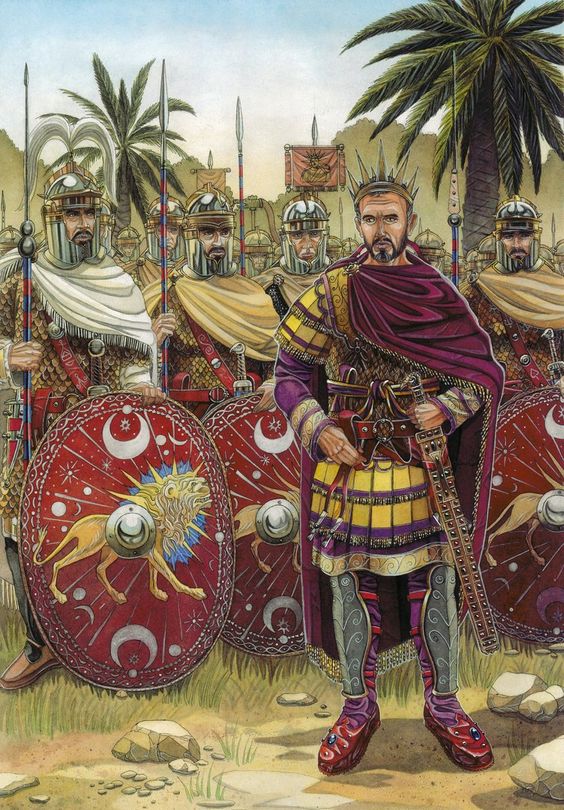

Aurelianus and the Praetorian guard by AMELIANVS on DeviantArt

Gallienus had also been directly challenged since 260 by Marcus Cassianus Latinius Postumus. This flamboyant pretender was governor of Germania Superior and Inferior when he was declared emperor by the Rhine garrisons. The western provinces had been placed under the rule of Gallienus’ teenage son Saloninus and it was not entirely surprising that the north-west Rhine garrisons preferred the option of an experienced leader. Postumus ended up creating and ruling a breakaway empire from Cologne that in every formal respect emulated the legitimate Empire; this probably included creating his own praetorians but there is no evidence to substantiate this. Postumus controlled Britain, Gaul and the German provinces in a regime now known as the Gallic Empire. Postumus, murdered in 268, produced a vast amount of coinage but, unlike that of Gallienus, none of it honoured specific military units, and the same applies to his short-lived successors who finally capitulated in early 274. Unusually for emperors of the era, Claudius II had died in 270 from the plague and not as a result of violence. He was briefly succeeded by his brother Quintillus, who was proclaimed emperor by the soldiers at Aquileia, but the declaration of Claudius’ cavalry commander Aurelian as emperor by the army in the Balkans proved a more enticing prospect. Quintillus committed suicide and Aurelian proceeded unchallenged, initiating a highly successful reign cut short by yet another conspiracy.

Aurelian’s praetorian prefect was Julius Placidianus, attested in the post on an inscription from the Augustan colony of Dea Augusta Vocontiorum (Drôme) in Gallia Narbonensis; he had previously served as prefect of the vigiles under Claudius II. The presence of Placidianus in Gaul reflected the very dangerous situation on Rome’s northerly borders, caused initially by the German Juthungi tribe, the Vandals, and next by the Alamanni. The absence of the praetorian prefect from Rome was certainly not new, and had become a necessary part of the increasing need to confront threats in various parts of the Roman world, especially in the third century. The idea of the Guard as an elite body of experienced and privileged troops with a permanent base in Rome was changing. The Guard now more resembled the ad hoc units of praetorians organized by the protagonists of the civil wars up to 31 BC.

The frontier threats faced by Aurelian were successfully fought off to begin with, but only at the price of rebellions breaking out in Rome. These seem to have included one by the mint-workers, led by the rationalis (official in charge) of financial affairs, Felicissimus. Aurelian returned to crush the rebels, which involved having to execute a number of senators and confiscate their property. Aurelian also devised a scheme in which estates were to be bought up along the Via Aurelia at state expense and then operated by slaves captured on campaign so that a perpetual free dole of wine, oil, bread and pork could be made to the Roman people. This peculiar brand of slave-serviced socialism never came off, either because of Aurelian’s premature death in 275 or because Julius Placidianus dissuaded him on the grounds that if the Roman people had been given wine then there would be nothing more to give them apart from chicken and geese.

During Aurelian’s reign the Castra Praetoria underwent its most significant change since its construction 250 years earlier. Aurelian ordered a vast new circuit of walls to be built round Rome. These would reflect the huge expansion of the settled area since Republican times, and also protect the city from the very real threat it faced from barbarian incursions across the frontiers. It may also have helped to contain a potentially volatile population. Building began in 271 and continued for the next decade. The walls survive in large part today and bear witness to the colossal effort and resources involved. The Castra Praetoria’s north and east walls formed part of this new circuit, the south and west stretches now facing inwards. The work was more complicated than simply joining the new walls up to the camp and bonding them in. The camp’s walls were raised again, adding to previous periods of elevation, and a new type of tower added which served as a buttress to help support the heightened walls.

Aurelian also faced a breakaway state in the east based around the great city of Palmyra under the queen, Zenobia. In 272 the regime’s city of Emesa fell to Aurelian in an engagement that included a hand-picked selection of praetorians as well as a huge array of legions and auxiliary forces.44 Palmyra fell too but Aurelian spared the city until a rebellion in 273 led him to destroy it. Aurelian could now turn his attention to the crumbling Gallic Empire. The last of Postumus’ successors, Tetricus I, capitulated to Aurelian in early 274 and participated in a triumph in Rome with Zenobia. In 275 Aurelian had to head east once more, this time to recover Mesopotamia from the Persians. En route in Thrace he became suspicious about his secretary Eros and evidently made an allegation to which Eros took exception. Eros decided to get his revenge by circulating a fictitious list of people whom he claimed Aurelian was planning to punish, encouraging them therefore to do what was necessary to save themselves. The outcome was almost inevitable: some of the accused, including a number of praetorian officers, watched Aurelian leave the city one day. They followed the emperor and killed him. The conspiracy and assassination were the consequence of an unfortunate misunderstanding but the incident proves that the Praetorian Guard was a routine part of the emperor’s field army.

Aurelian was succeeded by Marcus Claudius Tacitus, a senator of mature years. The Historia Augusta refers to an otherwise unknown praetorian prefect called Moesius Gallicanus, perhaps appointed under Aurelian, recommending Tacitus to the army on the grounds that the senate had made emperor the man the army wanted. Tacitus either replaced Gallicanus with, or appointed alongside Gallicanus, his brother Marcus Annius Florianus as praetorian prefect. Since Florianus was sent east by Tacitus to fight the Goths, we can legitimately assume that the Praetorian Guard went with him. Tacitus, however, died and Florianus seized the chance to declare himself emperor. This was not the intention of the army in Syria and Egypt, who preferred to sponsor their commander, Marcus Aurelius Equitius Probus instead. The two sides came to a potential battlefield at Tarsus but Probus avoided fighting and in the ensuing stand-off Florianus was killed by his own troops.

Prior to his accession in 276, Probus allegedly wrote to his praetorian prefect, Capito, reluctantly accepting the post of emperor. Unfortunately, Capito is otherwise unknown and the Historia Augusta for this period so unreliable in many ways that there is every possibility that ‘Capito’ and the letter to him were simply invented, unless Carus was meant. Even the hope expressed in the ‘letter’ that ‘Capito’ will stand alongside the emperor appears to have its origins in one of Cicero’s orations. However, there is perhaps a plausible basis in the context of Probus’ time where the praetorian prefect had become the emperor’s right-hand man. The reign was characterized by yet more endless frontier warfare. At Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica) in Pannonia (Serbia), Probus was killed in a rebellion led by Marcus Aurelius Numerius Carus who had been appointed by Probus as praetorian prefect early in the reign. Carus’ presence and involvement in the death of the incumbent emperor replicated a scenario that was becoming all too familiar. Carus did not last long. He was found dead in his tent in July 283 on campaign in Persia. This time the culprit seems not to have been an accidental lightning strike, as reported in the Historia Augusta, but his praetorian prefect and his son Numerian’s father-in-law, Lucius Flavius Aper, who allegedly believed his own chances of power were likely to be better served if Carus was extinguished and replaced by his sons. Carus’ adult sons, Carinus and Numerian, succeeded their father seamlessly, Carinus taking the western half of the Empire, Numerian the east. It was an arrangement that was to be used extensively in the century to come. By 284 Numerian had been killed. The Historia Augusta blamed Aper, which, if true, made him the first praetorian prefect to kill two emperors in succession. Aper was apprehended by the soldiers of the eastern army who nominated the commander of the domestici, ‘household troops’, Diocles, who immediately killed Aper. By 285 Carinus was in a position to challenge Diocles but was killed by one of his own officers during the battle at Margum on the Danube.

Diocles assumed the name Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus. As Diocletian he embarked on a sophisticated and disciplined recovery of the Empire. To begin with, he carried over Carinus’ praetorian prefect, Titus Claudius Aurelius Aristobulus. The reorganization culminated in 293 in the creation of the Tetrarchy, a collegiate system of emperors. He and another officer divided the Empire, Diocletian taking the east and Maximian the west as the Augusti. Each was assisted by a junior emperor, Galerius and Constantius Chlorus, known respectively as the Caesars. In time Diocletian and Maximian were to abdicate and hand over power to their Caesars who would then become the Augusti and appoint their own Caesars. The system was designed to avoid the appalling problems their immediate predecessors had experienced trying to govern a sprawling empire beset by endless frontier problems, internal rebellions and succession by force.

The logical inference is that each tetrarch had his personal Praetorian Guard, and this does appear to have been the case. The Guard, still referred to as the praetorian cohorts, was dispersed by Diocletian amongst each of the four tetrarchs, with only a skeleton garrison left behind in Rome to man the Castra Praetoria. In 303, during a period of Christian persecution, a church in Nicomedia was raided by the ‘prefect’ in a search for images of Christ. The attack was conducted while Diocletian and Galerius watched from the nearby palace, and was carried out by part of the Praetorian Guard in battle order suitably equipped with axes and iron weapons. They systematically destroyed the church. In the fourth century under the Tetrarchy and later the position of praetorian prefecture continued, even once the Guard itself had been disbanded.

From soon after Diocletian’s accession, Britain had been controlled by a rebellious former fleet commander called Marcus Aurelius Mauseaeus Carausius. Seizing power in 286, Carausius was a colourful usurper whose ideology of a renewed and revived Augustan Roman Empire in Britain was depicted on a highly unusual series of coins. Carausius’ power seems to have extended partly into northern Gaul since he was able to strike some of his coins at Rotomagus (Rouen), but this did not in any sense entitle him to the audacity of the military issues he had minted in Britain. These included coins which honoured some legions not based in Britain, such as the VIII legion Augusta and the XXII Primigenia, as well as those that were, such as II Augusta. Unless the coins were designated as a form of propaganda designed to entice these other legions into siding with Carausius, the only other explanation would be that detachments were then based in Britain. However, there is no other evidence to substantiate that, and so many legions are involved that the idea is implausible. It is much more likely that Carausius was simply trying to ingratiate himself with as much of the Roman army as possible. The series also included one with the legend COHR PRAET for the Praetorian Guard around four standards. The issue closely resembles one produced at Philippi in the first half of the first century AD in honour of the Praetorian Guard and was probably based on it. There are three possible explanations: Carausius had a detachment of Diocletian’s praetorians in Britain, he had his own praetorians, or he was trying to seduce the Guard into supporting him. The latter is the most likely, but there is no means of verifying this. It was the last time the Praetorian Guard was honoured on any coin issue. Clearly Carausius, who posed as a restorer of everything traditional about Rome, perceived the Praetorian Guard as an integral part of his manifesto and image.