In 1940 the War Office established the Camouflage Development and Training Centre at Farnham Castle in Surrey. It was the preserve of a mixed bag of individuals including Hugh Cott, a distinguished Cambridge zoologist who applied the coloration found on animal skins to guns and tanks. From the art world there was the Surrealist artist and friend of Picasso, Roland Penrose, who wrote the Home Guard Manual of Camouflage. Penrose’s party trick was successfully to hide his lover, the acclaimed American model, photographer and war correspondent Lee Miller, in a garden, naked, camouflaged from prying eyes with body paint and netting. He reasoned that if he could hide a naked woman in a garden full of people, anything could be hidden.

Perhaps the most famous of the British camoufleurs was the popular stage magician Jasper Maskelyne. Following the publication of his memoirs in 1949, Maskelyne has long been seen as the leading light in the deception world. However, the truth about the ‘war magician’ appears somewhat less fantastic under scrutiny. Maskelyne arrived in Cairo on 10 March 1941 as part of a detachment of 12 camouflage officers sent to work with Barkas. He spent much of his time performing magic shows for entertainment purposes and later went on to work for the escape and evasion department MI9, where he helped in devising concealed escape devices for POWs.

Maskelyne’s actual involvement in military deception appears to have been a bit of a sham. Curiously enough, people appeared much more confident with the dummy vehicles when they were told they had been devised by a well-known illusionist. It also appears that Dudley Clarke encouraged Maskelyne’s boasting to some extent, because it diverted attention away from A Force and himself. Somewhat ironically, then, Maskelyne’s main contribution to deception may have been to provide a cloak behind which others could work in secret.

Maskelyne’s more limited role is also suggested by the artist Julian Trevelyan, a fellow graduate from Farnham. An interesting character in his own right, Trevelyan was a member of the British Surrealist movement and before the war had experimented with injections of hallucinogenic synthetic Mescalin crystals, an experience which led him to exclaim: ‘I have been given the key of the universe.’ His feet firmly back on the ground, Trevelyan was sent from the United Kingdom on a fact-finding mission to the Middle East to witness the deceptions being carried out there by Barkas’s department.

In March 1942 Trevelyan visited Tobruk and then went to Barkas’s Camouflage Training and Development Centre at Helwan near Cairo. He was generally impressed with what he saw, except perhaps with a dummy railhead complete with dummy rolling stock and station, which he claimed that the Germans complimented by dropping a wooden bomb on. Having witnessed the hand of Barkas at work, the artist remarked: ‘It is thanks to Barkas, principally, that the formidable technique of deception has been elaborated. You cannot hide anything in the desert; all you can do is to disguise it as something else. Thus tanks become trucks overnight, and of course trucks become tanks, and the enemy is left guessing at our real strength and intentions.’

Returning to the situation at El Alamein, Barkas followed Auchinleck’s orders to congregate his dummies behind the main lines and was overjoyed that he, for the first time, received the magic words ‘operational priority’ to assist him. Operation Sentinel saw the land between El Alamein and Cairo become dotted with camps, complete with smoke rising from cookhouses and incinerators. Canteens were set up with dummy vehicles parked outside while their imaginary drivers were inside enjoying an equally notional ‘brew’. To thicken the defensive positions, the craftsmen at Barkas’s school at Helwan developed a wide range of decoys, including batteries of field guns that could be stowed inside a single truck. Within three weeks of starting the build up Barkas was simulating enough activity to indicate the presence of two fresh motorized divisions in close reserve to the main line.

After his failure to break through the Alamein line Rommel was forced onto the defensive. With an impatient Prime Minister anxiously watching proceedings, the British made their preparations for a counter-attack scheduled for 23 October. To cover this attack, two cover plans were developed, Operations Treatment and Bertram.

Shortly after Montgomery took command of the Eighth Army on 13 August he held his first meeting with Colonel Dudley Clarke and was given an appraisal of his command’s activities, which centred on maintaining a notional threat against Crete. Montgomery did not disapprove of Dudley Clarke’s tactics; in fact he endorsed them. When planning the counter-offensive, in addition to the notional threat against Crete, Montgomery wanted A Force to use its intelligence channels to make the Germans believe the start date, or D-Day, for the forthcoming Allied desert counter-offensive would be 6 November, two weeks later than actually planned. This A Force ruse was codenamed Treatment.

At the time, Dudley Clarke was heavily involved with the planning for Operation Torch. In October he was called to attend a meeting with the London Controlling Section, which was set up to ensure Anglo-American cooperation in deception once the US forces began operating in North Africa. As he would be away from Egypt at the crucial time, Clarke handed over management of Treatment to his deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Noël Wild.

Having been acquainted with him for some time before the war, in April 1942 Clarke had poached Wild from his job as a staff officer at GHQ Cairo. The circumstances of his recruitment were somewhat irregular. One evening Major Wild went to a Cairo hotel to cash a cheque and was ambushed by the A Force chief, who bought him drinks to celebrate Wild’s promotion to lieutenant colonel as Clarke’s deputy. When Wild enquired what the promotion entailed, and what exactly Clarke did, he was met with evasive replies. The only certainty was that Clarke wanted someone he knew and trusted in the post.

After a night’s sleep Wild accepted the position and was indoctrinated into the weird and wonderful world of A Force. By the time of Treatment, Wild was well enough versed in its techniques to use the A Force channels to hint that there were no plans to commit to a major offensive against Rommel. As long as German forces continued to advance into the Caucasus through the Soviet Union, the British were said to be apprehensive about their rear. Instead, Montgomery’s sole purpose was to use the lull in the fighting to train and test his troops for future operations. According to information sent out by the Cheese network, if there was going to be any major British attack it would be against Crete. This information was taken so seriously that Hitler ordered the island’s garrison to be strengthened on 23 September. He reiterated this order on 21 October, just two days before the British offensive was due to open.

To divert attention away from the last week of October, a conference was scheduled in Tehran. In attendance would be the British Commanders-in-Chief Middle East, PAIFORCE (Persia and Iraq) and India. This conference was scheduled for 26 October, three days after D-Day. In Egypt the last week of October was left open for officers to take leave and many had hotel rooms booked in their names.

The tactical counterpart to Treatment was codenamed Bertram and was given to Lieutenant Colonel Charles Richardson to devise and implement. An engineer by training, Richardson had only recently joined the planning staff of Eighth Army HQ after having spent a year with SOE in Cairo. Privately he was dismissive of the dummy tanks Auchinleck had used in Sentinel as a ‘pathetic last resort’. Richardson was sceptical about the chances of fooling the Germans, in particular the Luftwaffe and its photo-reconnaissance interpreters.

Richardson was summoned by Montgomery’s chief of staff, Freddie de Guingand, and received the outline of the British plan, which was a direct assault along the coastal road, on the right of the British position. He was then told to go away and come up with a suitable cover plan that would conceal the intention of the offensive for as long as possible, and when that was no longer possible, to mislead the enemy over the date and sector in which the attack was to be made.

For this purpose Montgomery wanted a plan that advertised false moves in the south, while concealing his real moves in the north of the sector. Pondering the situation from Rommel’s point of view, Richardson thought that the German field marshal might ‘buy’ the suggestion of a British attack from the south, as it was the sort of tactic he might resort to himself. The other thing Richardson had to consider was how to persuade Rommel the attack was not going to be delivered on 23 October, as was the case. The preparations for the battle were so vast that Richardson supposed they could only stall the enemy’s thinking by about ten days. The way he proposed to do this was ingenious. His idea was to construct a dummy pipeline bringing water to the southern flank. German reconnaissance would no doubt spot this pipeline and, by gauging the speed with which it was being constructed, they would be able to project the date on which the British would be ready to begin their operations. This date would be set at ten days after D-Day. Richardson took the plans to de Guingand, who approved them, and passed them on to Monty for his final endorsement.

With official approval granted, Richardson needed someone actually to implement the plans. Richardson was aware of A Force’s existence, probably through de Guingand, who had until recently been the Director of Military Intelligence in GHQ Cairo. However, Richardson was reluctant to use A Force because he believed Clarke’s work was so ‘stratospheric and secret’ it was best to keep well out of it. Instead Richardson used GHQ’s Camouflage Department under Barkas.

On 17 September Barkas and his deputy, Major Tony Ayrton, were invited to de Guingand’s caravan and warned that what they were about to hear was top secret. The Chief Engineer of the Eighth Army was about to make a number of bulldozed tracks running from an assembly area codenamed Martello towards the front line, running parallel with the coast road and railway. Shortly afterwards large concentrations of vehicles and tanks would begin concentrating at Martello along with vast quantities of stores and munitions. Beyond Martello, but about five miles behind the front line, a great number of field guns would be marshalled at an area codenamed Cannibal 1. These would then be moved closer to the front line to deliver an opening barrage from positions directly behind the front line codenamed Cannibal 2. De Guingand wanted to know if the Camouflage Department was able to assist with the following objectives:

1. To conceal the preparations in the north.

2. To suggest that an attack was to be mounted in the south.

3. When the preparations in the north could not be concealed, to minimize their scale.

4. To make the rate of build up appear slower than it actually was, so that the enemy would believe there were still two or three days before the attack commenced.

Although sobered when told he had about a month to achieve all this, Barkas was inwardly jubilant that at last Camouflage was about to make a ‘campaign swaying’ contribution.

Barkas and Ayrton left the caravan to formulate their plan and took a stroll along the beach where their voices were drowned out from prying ears by the waves breaking on the shore. Two hours later, having typed up an appreciation and report on the subject, they went back to de Guingand, offering to suggest

For this purpose Montgomery wanted a plan that advertised false moves in the south, while concealing his real moves in the north of the sector. Pondering that two armoured brigade groups were concentrating to the south. When Montgomery’s reply was delivered a few days later, Barkas was told to make provision for an entire phantom armoured corps in the south.

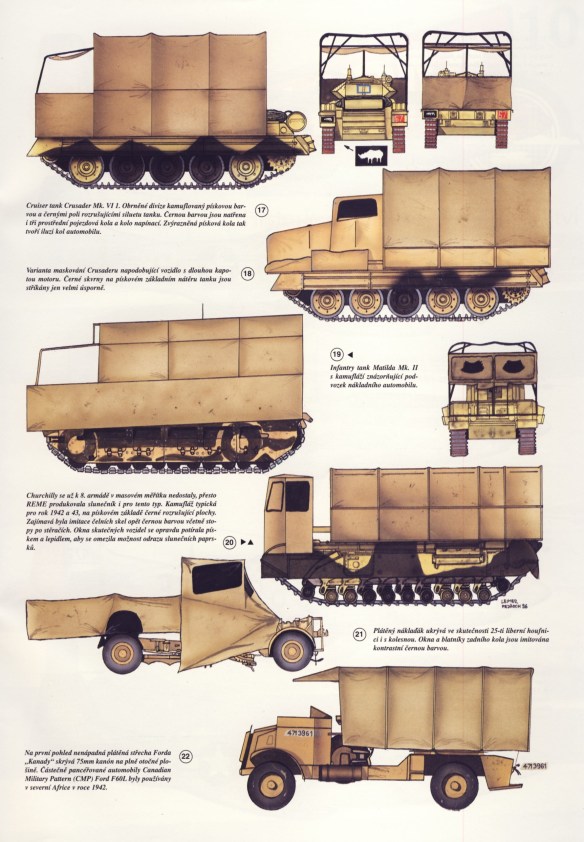

This entailed making 400 dummy Grant tanks and at least 1,750 transport vehicles and guns. Barkas was given ample resources, including three complete pioneer companies, a transport company and a POW unit. While he masterminded production of the material and devices, Barkas charged Ayrton and his colleague, the former Punch illustrator Brian Robb, with the actual deception work on the battlefield.