Byron implies that Rupert prevaricated and thereby lost the chance to inflict a major reverse on the Parliamentarian army:

we were placed that we had it in our power both to charge their horse in flank and at the same time to have sent another party to engage their artillery, yet that fair occasion was omitted, and the enemy allowed to join all their forces together.

Prince Rupert’s Diary places the blame elsewhere, explaining that Rupert had deployed his forces in preparation for an attack when a cabal of senior officers including Wilmot, Digby and the queen’s favourite, Colonel Henry Jermyn ‘importuned the prince not to fight’. Rupert was enraged and while the generals argued on their hilltop, the Parliamentarian horse and foot combined in the valley below and the opportunity was indeed lost.

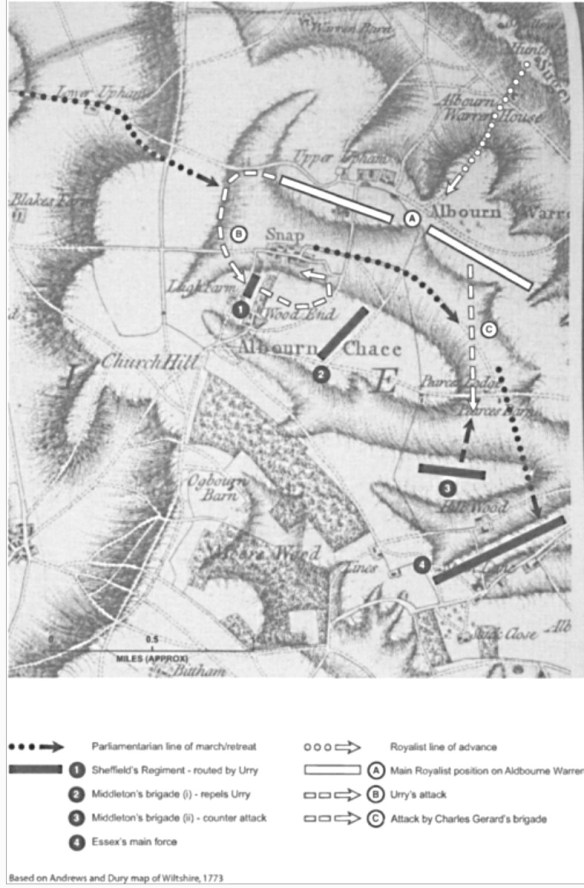

Neither interpretation tells the full story. Despite Byron’s criticism, other contemporary accounts show that the prince’s opening move was decisive enough. Noting that some at least of Middleton’s rearguard was still isolated from the main body, Rupert sent Urry with 1,000 cavalrymen to circle around to the west to take them in the flank. How far Middleton’s men were from the security of Essex’s infantry and artillery is unclear. According to Mercurius Aulicus they were on the far side of a ‘village’, probably a reference to Snap, a substantial medieval settlement reduced in the seventeenth century to a single row of cottages. In that case, Middleton was still perhaps half a mile or more from the rest of the army.

Urry was able to outflank the rearguard without being observed. He could have used any one of a number of ridges to hide his progress from the opposite slopes, where Middleton’s troopers were slowly shepherding the baggage towards the safety of the infantry. Middleton had five regiments with him, well over a thousand men, but 200 or so were at the very rear of the column, standing on another ridge. This was probably Colonel James Sheffield’s Regiment. Their attention was presumably focused on the main Royalist formation so that they did not see Urry’s detachment until too late and were quickly overwhelmed by a savage surprise charge. As the Royalist cavalry poured along the valley, firing pistols and carbines as they came, disorder spread through the Parliamentarian rearguard. Some of the baggage train was abandoned. Two ammunition carts overturned and by one account exploded. The Royalists claimed to have killed forty or fifty and captured two officers. Even the official Parliamentarian report conceded that ‘the enemy pursuing hotly both on rear and flank, our retreat was not without some confusion and loss’. Sheffield’s Regiment lost a standard and took no further part in the day’s events.

Urry could not charge the entire Parliamentarian army with 1,000 cavalrymen. He was already coming under ineffective fire from the light guns deployed among the infantry. But from the opposite hillside, it seemed that his surprise attack had so unnerved Essex’s whole army that Rupert was tempted to bring the rest of his force down into the valley to mount a full attack. Perhaps this was Byron’s idea, which was why he was piqued when it was not followed. Digby explained, however, that at that moment news arrived that ‘our foot, was beyond expectation, advanced within six or seven miles of us’. This ‘imposed upon his Highness prudence’ and it was decided to wait for these reinforcements to arrive the next day before seeking battle. Meanwhile, the Royalist cavalry would continue to ‘hinder their march’. Taken at face value, Digby’s explanation appears implausible. As discussed above, on 18 September the main body of Royalist infantry was well to the east, trudging from Alvescot towards Newbury; King Charles was at Farringdon for dinner and Wantage for supper, at no time nearer than twelve miles from Aldbourne. Even if diverted, the Royalist infantry would not arrive until late on the following day. A more credible explanation is that the reinforcements were Lisle’s musketeers, who should certainly have arrived by the next morning. If Rupert could keep Essex pinned down overnight in the steep-sided valley bottom, 1,000 musketeers would improve substantially his ability to harass the Parliamentarians throughout the following day, thereby increasing the likelihood that the king would then win the race to Newbury. This is probably when Digby, Wilmot and Jermyn urged caution and the Parliamentarians were able to regroup.

Whatever the reason, Rupert decided not to press home Urry’s advantage. There was some skirmishing between dismounted dragoons, and the prince and his advisers may have expected that this and the continuing threat of cavalry attack would be sufficient to deter Essex from attempting to disengage. They were wrong. Digby wrote that they ‘had not stood long, when we discovered that the enemy prepared for a retreat, and by degrees drew away their baggage first, then their foot, leaving their horse at a good distance from them’. Middleton had rallied his regiments and they now covered a slow withdrawal. Although disengagement in these circumstances was a difficult and risky operation, the Parliamentarians had noted that the Royalists had no infantry present. Rupert had shown on the Cotswolds that he was unwilling to commit his cavalry alone against the pike walls and musket volleys of formed infantry brigades. The valley’s southern slope is relatively steep. Though the artillery was scrambled up it, the rustled sheep and cattle were abandoned, together with three cartloads of ammunition and fourteen carrying wheat or other foodstuff. When the infantry reached the top, they deployed again to cover the rest of the baggage train and wait for Middleton’s cavalry to rejoin them. They were now little more than a mile from Aldbourne village and the ground would become increasingly enclosed as they descended towards it from the Chase.

As at Stow-on-the-Wold, Essex seemed to have faced down and evaded the Royalist cavalry. This time, however, Rupert decided not to stand idly by. According to Digby, his initial inclination was to launch a full-scale attack before the Parliamentarian army could follow their baggage train into the lanes in front of the village. But dusk was falling and the Parliamentarian withdrawal was happening so slowly that the prince chose instead to try to provoke Middleton’s rearguard, which was still in the valley, into fighting rather than retreating. These tactics smack of another compromise between the combative prince and his more cautious senior officers so it is not surprising that Rupert turned yet again to the like-minded Urry. Across the valley, some of Middleton’s force had already started to make their way up the slope. With about 500 commanded men, Urry moved forward to engage the remaining regiments before they too could withdraw. To tempt Middleton to fight not flee, Rupert gave Urry little immediate support. Two regiments only followed him down onto the valley floor. Nonetheless, for the second time that day, Urry carried all before him, at least to begin with, putting the tail end of the Parliamentarian rearguard ‘into the like disorder’.

The ploy succeeded in drawing Middleton back into the valley. At the head of his own regiment and three attached troops, together probably similar in strength to Urry’s force, he counterattacked the Royalists with unusual effectiveness. His men will have been charging downhill and in tight order, whereas the Royalist had lost their formation in the first clash. As Urry was pressed back down the slope, the two supporting Royalist regiments should have intervened but Digby admitted that they did not do ‘their part as well as they ought’ and Urry was ‘forced to make somewhat a disorderly retreat’. Middleton’s troopers now turned on the two supporting Royalist regiments, probably part of Gerard’s northern brigade, who were also routed. Digby commented ruefully that while Rupert’s aim had been to tempt the Parliamentarian cavalry to engage, they had done so ‘with a little too much encouragement’.

Nevertheless, the prince persisted with his plan. Rather than commit his full strength, which would have obliged Middleton to retreat, he ordered a third detachment forward into the valley. The Queen’s Regiment of Horse was the largest regiment in Gerard’s brigade, with as many as 500 officers and men, including mercenaries and French volunteers. At its head rode Jermyn, newly ennobled at the queen’s request as Baron Jermyn of St Edmundsbury, with Digby and the Marquis de Vieuville, a young French nobleman, at his side. In their own minds, they were the elite of the Royalist horse. By the time that the Queen’s Regiment had made its way down the slope into the valley, Middleton’s men had reformed. When the Royalists attacked, they were received not by a counter charge but by an old-fashioned volley of pistols and carbines. Digby wrote with approval of the unusual steadiness of the Parliamentarian cavalry who waited until the Royalists were within ten yards before firing, and in particular of the remarkable composure of their commander, presumably Middleton, who peered at the Royalist commanders in turn before deciding

to discharge his pistol, as it were by election at the Lord Digby’s head, but without any more hurt (saving only the burning of his face) than he himself received by my Lord Jermyn’s sword, who (upon the Lord Digby’s pistol missing fire) ran him with it into the back; but he [Middleton] was as much beholden there to his armour, as the Lord Digby to his headpiece.

Past precedent suggested that the momentum of the attacking Royalists would sweep away the static Parliamentarians, but as the Queen’s Regiment drove into Middleton’s men they were themselves charged in the flank or rear. Colonel Richard Norton led his own regiment and that of Colonel Edmund Harvey into the mêlée. The Parliamentarian rearguard was becoming increasingly embroiled as Rupert intended, yet they were also fighting with unexpected vigour. Jermyn’s regiment recoiled from the surprise assault, ‘the greatest part of it shifting for themselves’. The officers, at the head of their troops and already hacking and slashing at Middleton’s front ranks, were suddenly deserted and isolated. Unable to retreat and with his arm shattered by a pistol ball, Jermyn showed great presence of mind by leading his officers through Middleton’s Regiment, which had been disrupted by the initial impact of the Royalist charge, past a body of Parliamentarian infantry and around the edge of the action back to their own lines. He had, however, lost de Vieuville who had been hit three times, in the chest, shoulder and face, although reports published in London suggested that he was actually killed by a blow from a pole-axe when he tried to escape from a lieutenant who had captured him. Stunned and blinded by the pistol shot to his helmet, Digby too was taken prisoner.

Essex’s rearguard were now completely committed, and the earl had sent a party of dragoons and musketeers from his own regiment back into the valley to support them (they were the infantry that Jermyn evaded), and recalled the rest of his cavalry. Urry, Gerard and Jermyn having been defeated in detail, Rupert led his own brigade, probably 1,000 or so strong, down the steep slope in an effort to regain the initiative. Even now, the despised Parliamentarian cavalry stood their ground. Grey’s and Meldrum’s regiments, supported by the musketeers, saw off the first Royalist charge but the prince reformed his men and at the second attempt broke the Parliamentarian line and sent them retreating back towards the main body. From the hilltop, Foster thought that the cavalrymen ‘performed with as brave courage and valour as ever men did’. Digby was

fortunately received out of the middle of a regiment of the enemy by a brave charge, which Prince Rupert in person made upon them with his one Troop, wherein His Highness’ horse was shot in the head under him.

Rupert had to accept that his men could achieve no more. The Parliamentarian cavalry had reformed on the slope under the guns of the infantry brigades where the Royalist horse had no hope of following. Moreover, Middleton’s rearguard had been reinforced by Sir Philip Stapleton with the remainder of Essex’s cavalry regiments, together with the Trained Band and Auxiliary Regiments, so that Rupert was clearly outmatched. With night falling, the prince withdrew to his original position on the far side of the valley. Skirmishing between dragoons continued for an hour or so, but the main action was over.

The Parliamentarians claimed to have inflicted heavy losses, and to have captured up to sixty prisoners, including a lieutenant colonel and four other officers, but they also admitted two or three of their own captains killed, numerous other officers injured and ‘some common soldiers slain’. A Parliamentarian soldier told a London newspaper that about 100 from both sides had been killed. Essex’s biographer, Codrington, later estimated a combined total of 80 dead and more than 80 wounded. The Royalists were especially concerned about de Vieuville, who was believed at first to have been taken prisoner, but Hyde later acknowledged that many other officers had been wounded.

Aldbourne Chase had been a hectic cavalry skirmish of the kind at which Rupert usually excelled. On this occasion, however, Essex and the Parliamentarian horse had taken the tactical honours. Byron’s sarcastic comment that no action was taken until the enemy had joined their forces together, after which ‘we very courageously charged them’ is justifiable criticism of the action as a whole. Yet Rupert’s mistake was not to do too little, but to attempt too much. His unexpected appearance imposed delay on the Parliamentarian march; Urry’s original charge was sufficient to persuade Essex to abandon seventeen wagons and one thousand hobbled sheep; a full-scale attack during the afternoon could perhaps have inflicted further damage. But once the prince had accepted, however reluctantly, the advice of Wilmot and Digby not to provoke a major battle, the evening’s skirmishing had done little more than further tire and frustrate his own men, and boost the morale of the Parliamentarian cavalry.