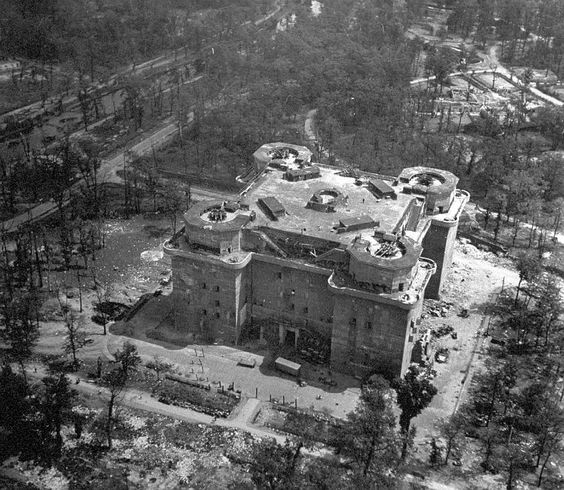

Tiergarten Flak Tower – Generation 1 – (Flakturm Tiergarten) with twin 12,8 cm Zwillingsflak 44, Berlin, 1945.

The Flakturm (Flag Tower) is a concrete bunker that is placed in a city. The bunker was provided with a space where people (in the largest tower itself was room for 20,000 people) could shelter during bombings and there was space for storage of goods. The bunker was equipped with Flak anti-aircraft gun (Flak is the acronym for Flugabwehrkanone, also called Fliegerabwehrkanone).

These large towers were built during the Second World War in the cities Berlin (Germany), Hamburg (Germany) and Vienna (Austria).

Each Flak tower complex consisted of a G-Tower (Gefechts-Turm) and L-Tower (Leit-Turm).

The complexes consisting of 3 generations:

Generation 1:

G-Tower – 70.5 x 70.5 x 39 meters – with eight 128 mm guns and several 20, 30 and 37 mm guns.

L-Tower – 50 x 23 x 39 meters – usually equipped with sixteen 20 mm guns.

Generation 2:

G-Tower – 57 x 57 x 41.6 meters – equipped with eight 128 mm guns and sixteen 20 mm guns.

L-Tower – 50 x 23 x 44 meters – equipped with forty 20 mm guns

Generation 3:

G-Tower – 43 x 43 x 54 meters – with eight 128 mm guns and 32 pieces of the 20 mm gun.

X

With Allied forces advancing from the west, east and south and a northerly route of escape cut off by the sea, the noose was finally closing around Hitler’s “1,000-year” Reich. Berlin, of course, was to be the scene of final destruction and in the last two weeks of the war in Europe the Germans prepared to defend their capital as best they could.

The east side of Berlin was strongly fortified, with three separate lines of anti-tank defences. In the city centre, every street was to be turned into a strong point. Hitler had hoped to make Berlin into a fortress and it was certainly given many of the relevant features. Ringed around the city were three structures which echoed the castles of medieval times. These were the flak towers, three huge concrete structures with walls so thick that not even the heaviest artillery shells could penetrate them. The first, known as the Humboldt Tower, after the famous German oceanographer, was located just off the Brunnenstrasse in the north of Berlin. The second was just to the east of the city centre, on Landsberger Allee, and the third was in the south-west of the city centre, at the Zoo.

The original purpose of these flak towers had been to serve as anti-aircraft gun platforms to protect Berlin against the frequent Allied bombing raids. Each of the enormous gun towers had a satellite tower a short distance away from where artillery observers controlled the anti-aircraft fire. After the Russians beat off a last desperate stand on the Seelow heights east of Berlin, pouring down such a weight of artillery fire that the defenders had to retreat, the last natural obstacle into the city was open to them. Now the onus was on the defence ring hastily thrown up around Berlin and on the flak towers, which were virtually impregnable.

In 1945, with the dreaded Russians almost at the gates, these defences were to protect not only Berlin, but also the heart of the Nazi regime, located in a bunker close to the Chancellery building on Wilhelmstrasse. They were also meant to preserve the nearby key city landmarks of the Brandenburg Gate, the famous Unter den Linden and the Reichstag on Königsplatz.

In his bunker, Hitler was obsessed with dreams of glory that would never come true. At the start of 1945 he had dismissed as ridiculous fantasy the idea that the Red Army was about to launch a major offensive into Germany and even at this late hour clung to the illusion that forces commanded by SS Lieutenant-General Felix Steiner were going to link up with the surviving German forces north of Berlin and strike a decisive blow against the Russians. Steiner had no more than a ragbag of forces, the grandly named Group Steiner, that was incapable of even scratching the Russian advance. The Russians simply brushed them aside as they completed their encirclement of the Nazi capital.

Finally, Hitler turned to Colonel-General Gotthard Heinrici, commander of the Army Group Vistula, including the Ninth Army, which, he fancied, was going to march into Berlin any day and save the Reich and its Führer from the communist devils. Heinrici was an experienced professional from a family with a military tradition going back eight centuries. He was supposed to be responsible for the defence of Berlin, but he knew a lost cause when he saw one. Like Schörner, he ordered his troops away from the capital, advising them to surrender to the British or the Americans. Hitler ineffectively dismissed Heinrici on April 28 and returned to his illusions. He spent his time moving flags on a large map, apparently believing that they represented real military forces. He remained unaware that his new mighty “armies” consisted of a few small groups and defenders holed up in Berlin’s flak towers.

Hannau Rittau was a gunner in the Zoo flak tower. He was prepared to do all he could to defend Berlin, his birthplace, but like Heinrici, he knew it was hopeless:

You could see what was happening, the Russians were drawing closer and closer to Berlin and when they started firing on Berlin with their artillery we said, “Well, this is the end!” But I was born and raised in Berlin and we had to defend our home, just as we had to defend our country. That’s what we tried to do.

I was lucky to get into the tower at the Zoo. There was an army and an air-force hospital on one floor, though in the end we had wounded solders and civilians on all the floors. I think there were 3,000 people in this tower. My job was to drive the ambulance and bring the wounded to the tower from outside, so it was easy for me to stay there.

The tower came under determined Russian attack for two days and two nights. Despite the safety Rittau and the others had found in the tower, it was a frightening experience:

The Russians were firing at the tower all the time. The noise of the exploding artillery against the walls was terrible, the walls shook all the time. They couldn’t get through because the concrete of the tower was so thick and strong.

Even so, at one o’clock in the morning of May 2, the tower was surrendered to the Russians. We were told to stay at our stations, which we did. The first thing I remember after that was the door opening. A Russian tank driver came in and said, “Everybody kaput, everybody kaput, ja? Everybody kaput, ja? Don’t be frightened, Russian soldiers are good. The bad things you’ve heard about us were all propaganda.” And out he went again. That was our first contact with the Russians.

A few hours later the Russians came round looked at everybody. The wounded soldiers were lying on the floor, we had no beds, the wounded were on blankets on the hard floor. The Russians started stealing their watches, as they did with everybody. They were very interested in watches. We looked after the wounded, as we had done before. We had enough food in the tower because there was enough food storage in there for the whole of Berlin.

Although the Russians did not appear to be particularly dangerous or violent, Rittau decided to escape from the tower:

I tried to get out, because we hadn’t seen any fresh air all the time, you never saw daylight in this tower. I was on the third floor. I went downstairs and there was just one Russian standing on guard there. I gave him a cigarette. That seemed to please him. I was in hospital dress, all in white, so that he could see that I was a member of the hospital team. I looked around, and then went back into the tower again.

During the next two days, all of a sudden they starting making lists. The Russians came around asking, “What’s your name? What’s your grade? What was your last regiment?” “Oh, oh!” I thought to myself.

“This is getting dangerous. I’d better get home!”

It was May 6 by now. The Russians on guard were so used to seeing me that they didn’t notice when I slipped out of the tower. It was easy. I did the same thing again, I was wearing my uniform, but I had removed all the insignia. I pulled on my white hospital dress over it, went out the door and walked away, just like that! Of course, I tried to keep out of sight of any Russian soldier in the street who might ask me, “Where is your pass or your pay book?” or goodness knows what, and I walked home. Although my parents’ house was quite close to Berlin, I didn’t arrive until seven in the evening, after 10 hours.

Walking all the way, it took a long time because I tried to avoid any Russians wherever I could see them. I just ducked away out of sight and waited until they had passed by.

Ulf Ollech, formerly of the Luftwaffe, was in a rather more exposed position than Rittau. He helped to man an artillery battery in the environs of Berlin. Members of the Volkssturm, the citizens’ militia, were also there. This body, consisting of Hitler Youth and older men up to the age of 65 or more, had been specially trained with the Panzerfaust, also known as the Faustpatrone. This was a deadly anti-tank weapon which fired a hollow-charge projectile effective at 33 yards. In the battle for Berlin, groups armed with the Panzerfaust went hunting for Russian tanks and destroyed so many of them that the wreckage littering the streets actually obstructed the Russian advance.

Ollech was, however, disturbed at the idea that the Panzerfaust and their other weapons were going to kill people:

I was only 17, but suddenly I had to shoot at human beings in order to preserve my own life. We were trained with artillery, and were stationed on one of Berlin’s arterial roads, the Prenzlauer Allee, it was called. Work began at 0700 hours – practice with the artillery and training, training, training. Then we were transferred further to the north-east, to the eastern edge of Bernau. We set up positions on the road, but were then transferred at night to a place called Malchow, where we had a free field of fire on the road closer to Berlin, near the Weissensee – a free field of fire towards this road.

The Volkssturm troops were in the trenches in front of us. Behind us were residential areas with trees and houses and gardens, so that we were well camouflaged; and we expected, quite rightly, that the Red Army would come along this road straight past us. We had to be patient. During the course of one day, in terrible weather and soaking rain, walking through the trenches meant that you carried the mud and filth with you. We spent the night there, half awake, half asleep, and the next morning, when the sun rose, we heard they were advancing along this road. Because it was an asphalt road, the Russians could see exactly whether or not someone had been laying mines there. But it was free of mines and so they advanced.

Four T-34s, two Shermans and an assault tank came along. The road had a small bend and before the first tank had reached this bend, we started firing. We had an artillery gun, which had a velocity of 1,200 metres per second, the only gun in the world from which the shell left the barrel at such speed. That meant that the discharge and impact, especially at a distance of 200, perhaps 300 metres, was so short that you thought the discharge and the impact were the same sound. The tanks were all destroyed and the Red Army infantry at the rear of the tanks dispersed.

The wrecked tanks glowed red throughout the night and the ammunition inside exploded. We spent that night there, and the next morning the weather was dry, we discovered that the infantry units, in the shape of the Volkssturm, had gone, vanished. They were supposed to be in front of us and we had seen them the day before, but now they were nowhere to be seen.

That, of course, scared the wits out of us, because we knew that if the Red Army infantry had come at us overnight, we could never have fought them off. The next morning we ate a little and drank some tea, and then we got the order to retreat with our unit into the town proper, because the Red Army, primarily the infantry, but also the tanks, had already gone around us and broken through into the suburbs.

Ollech’s part in the battle of Berlin ended in one of Berlin’s flak towers, which was under siege by the Russians:

We retreated and retreated and we finally ended up in a flak tower – there were three of them in Berlin – and we got ourselves over to one of them. It was surprisingly comfortable. The food was good – I had the most glorious pea soup I had ever tasted in my life – and each of us had a plank bed, a cupboard, and everything was in first-class condition. We kept guard outside for four hours, then two hours inside.

The Russians started firing at the tower with their tanks. You could hear them. Their shells went “Clack-clack” as if someone was knocking on a door. That wasn’t good enough for the Russians, so they brought up some 15cm howitzers. They managed to make tiny holes in the concrete. There were windows which were closed from the outside with heavy steel doors, I imagine that they weighed tons, and the Russians succeeded in hitting the upper hinge of one of the doors, which burst. One of them broke off, twisted off the other one and hurtled downwards. Apart from that, the flak tower wasn’t badly damaged at all.

They then brought up a light artillery piece. A tank attack at night followed; they knew that we were lying in relays in the surrounding trenches. We had never experienced a tank attack at night before, and that was perhaps the most awful experience, because they attacked and we sought cover, and fought them off. Next morning we saw Russian corpses hanging over the edges of the trenches, with their machine guns dragged halfway. The Russian MGs were on wheels. You could hear when they were being pulled across a street because they rattled, “rat-a-tat-tat”.

Then came April 30, when we learned that Hitler and his wife had committed suicide. Hitler had once said: “I am National Socialism, if I no longer exist, there will be no more National Socialism; in other words, everything was focused upon him. We young men were very upset. We’d believe him when he’d said that. We’d grown up with it. We felt he had let us down. It was like losing an all-powerful father. What was going to happen to us now? we wondered.

It seemed hopeless for us to carry on. On May 2 we surrendered the flak tower.