British plan for the Peenemünde raid.

Although the ground controllers were fooled into thinking the bombers were headed for Stettin and a further ‘spoof by eight Mosquitoes on 139 Squadron led by Group Captain ‘Slosher’ Slee aiming for Berlin drew more fighters away from the Peenemünde force, forty Lancasters, Halifaxes and Stirlings (6.7% of the force) were shot down. In the wild mêlée over the target, Nachtjagd actually claimed 33 aircraft, total claims from the Peenemünde force amounting to 38 victories.

One of the victors was Hauptmann Peter Spoden of 5./NJG5 whose first victory between Hanshagen and Greifswald was Lancaster III JA897 on 44 Squadron at Dunholm Lodge piloted by Flight Sergeant Johnnie Drew (KIA). Spoden would become one of Germany’s leading ‘Tame Boar’ pilots.

‘I was still in high-school in early 1940 when a few RAF aircraft bombed the surroundings of my home-town Essen in the industrial Ruhr-district. My parents, sisters and relatives were living in Essen and as a young man of 18 years I had to become a soldier anyhow. My father, a former soldier and wounded in 1914-1918, was against the National Socialist party and any militarism and told me: ‘Don’t go to the infantry, you have no chance.’ So I decided to volunteer for the Luftwaffe, to become a Night fighter hoping to protect my hometown. Like many young men I was impressed by the strong army and the Luftwaffe. In October 1940 my application for the Luftwaffe was accepted, also because I was a glider pilot in the time before the war. The training for a night fighter pilot lasted 27 months including blind-flying and radar exercises on many aircraft like the FW 158, Ju 52, He 111, Bf 109 and mostly Bf 110. The training was excellent and helped me very much after the war when becoming an airline pilot. Early in summer 1943 (21 years old) after having finished the night fighter training I joined II/NJG5 in Parchim, Mecklenburg for protection of Berlin. Hauptmann Rudolf Schönert was my Gruppenkommandeur. Essen was already heavily bombed by the RAF, our house damaged, my mother, two little sisters and grandma evacuated to South Germany.’

In his first attack on the night of the Hamburg raid, 27/28 July, 22-two-year-old Leutnant Peter Spoden of 5./NJG5 at Parchim airfield could not find anyone in his Bf 110 because of ‘Window’. Now, at Peenemünde it seemed that he might be frustrated again by the enemy’s clever ‘Spoofing’ tactics, as he recalls.

‘The British tricked us. There were 200 fighters over Berlin being held by six Mosquitoes. I was there. Then we saw that it was on fire in the north but it wasn’t Berlin. They had ordered us to stay in Berlin and it had started to burn in Peenemünde. We flew there very fast. I shot one down. At that particular moment you do not think about the other crew. You have to shoot between the two engines and we had been trained to do that. It was said, ‘Shoot between the two engines, it will go on fire and they will have a chance to bail out.’

So I shot between the two engines to give them a chance to bail out. When I shot somebody down I was so excited. I landed and went to the crash site and spoke to the only survivor [Sergeant William Sparks, bomb aimer]. I felt free, as if I had achieved what I had been trained to do. How can I explain how I felt? Like an avenger for Essen.’

Two crews flying Bf 110s fitted with ‘Schräge Musik’ found the bomber stream and destroyed six bombers. Unteroffizier Holker of 5./NJG5 shot down two Viermots and Leutnant Peter Erhardt destroyed four within half an hour. Towards midnight, thirteen II./NJG1 crews left Sint-Truiden/Sint-Trond for the Gruppe’s first ‘Wild Boar’ operation of the war. They returned with claims for thirteen victories, mainly over Peenemünde, nine of which were consequently confirmed by the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM or Reich Air Ministry). These included five ‘Schräge Musik’ kills by 20-year old Leutnant Dieter Musset and his bordfunker Obergefreiter Helmut Hafner of the 5th Staffel, which were their first (and last) victories of the war. Whilst attacking their sixth bomber of the night Musset’s cannon jammed and their Bf 110G-4 G9+JN, was subjected to ferocious return fire. Wounded, Musset and his bordfunker bailed out to the north of Gustrow. Musset’s ankles had been broken. When he had recovered from his injuries he joined Stab II./NJG1. He was severely injured in a crash in bad weather on 7 February 1945, crashing at Harderode. Oberfeldwebel Otto Moll, bordfunker and Feldwebel Willi Heizmann, bordshütze were killed. Musset died of his injuries two days later. Leutnant Helmut Perle of Stab NJG2 in a Bf 110G-4 claimed a fighter ten kilometres north of Peenemünde. He was killed on the night of 30/31 August after scoring a double victory southwest of Mönchengladbach.

Nachtjagd also successfully employed ‘Zahme Sau’ (‘Tame Boar’) free-lance or Pursuit Night Fighting tactics for the first time since switching its twin-engined night-fighting crews from the fixed ‘Himmelbett’ system. ‘Zahme Sau’ had been developed by Oberst Victor von Lossberg of the Luftwaffe’s Staff College in Berlin and was a method used whereby the (‘Himmelbett’) ground network, by giving a running commentary, directed its night fighters to where the ‘Window’ concentration was at its most dense. The tactics of ‘Zahme Sau’ took full advantage of the new RAF methods. Night fighters directed by ground control and the ‘Y’ navigational control system were fed into the bomber stream (which was identified by tracking H2S transmissions) as early as possible, preferably on a reciprocal course. The slipstream of the bombers provided a useful indication that they were there. Night fighters operated for the most part individually but a few enterprising commanders led their Gruppen personally in close formation into the bomber stream, with telling effect (Geschlosser Gruppeneinsatz)-Night-fighter crews hunted on their own using ‘SN-2’ AI radar ‘Naxos Z’ (FuG 350) and Flensburg (FuG 227/1).

‘SN-2’ recalls Oberleutnant ‘Dieter’ Schmidt, Staffelkapitän, 8./NJG1 ‘was a great improvement on Lichtenstein, which worked on a wavelength of 53 centimetres, had a search angle of 24° and a maximum range of 4000 metres. SN-2 worked on a wavelength of 330 centimetres had a search angle of 120° and a maximum range of 6500 metres! With this equipment, wide-ranging night fighting, independent of the target being attacked and dependent solely on general reports of the situation and one’s own navigation, again became possible. For the individual crews, ‘Zahme Sau’ frequently involved more than one sortie per night. Almost invariably landings were away from base; such as take-off at Laon, an approach via Osnabrück to Frankfurt and landing at Mainz-Finthen, or take-off at Laon, attack over Berlin, Abschuss of a departing bomber after three hours flight and landing after three and a half hours at Erfurt. (The usual airborne time was only three hours). The early finding and infiltrating of the bomber stream, whose progress was soon marked by Abschüsse of other crews but occasionally also by turning-point markers or the dropping of incendiaries was decisive. Now, during all major attacks, all available night fighters were whenever possible assembled over radio or light beacons to be directed early on into the bomber stream. Although there was no traffic control at these assemblies – an unthinkable procedure in peacetime – resulting losses were rare.’

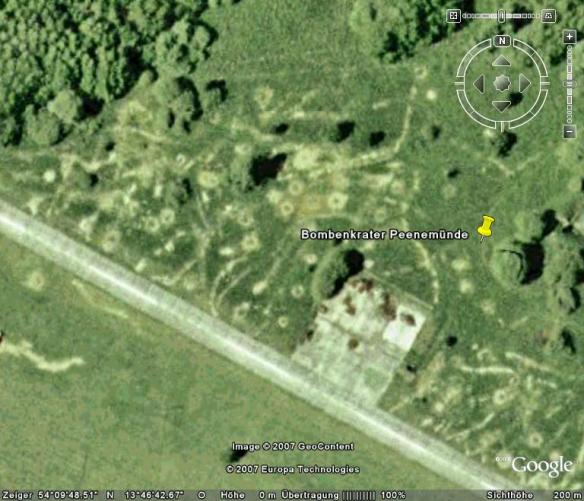

Out of the total of 606 aircraft assigned, twenty-three Lancasters, fifteen Halifaxes, two Stirlings and one of the Mosquitoes were lost (6.7%); 32 suffered damage. In England initial reports on the morning of the 18th indicated that the raid had been a complete success achieved through the element of surprise, the decoy raid on Berlin and the sheer audacity of operating under a full moon and clear skies. In the daylight reconnaissance twelve hours after the attack, photographs revealed 27 buildings in the northern manufacturing area destroyed and forty huts in the living and sleeping quarters completely flattened. The foreign labour camp to the south suffered worst of all. The whole target area was covered in craters. The initial marking over the residential area went awry and the TIs fell around the forced workers camp at Trassenheide where 500-600 foreign workers, mostly Polish, were trapped inside the wooden barracks. Once rectified Operation ‘Hydra’ went more or less according to plan and a number of important members of the technical team were killed. They included Dr. Walther Thiel. 1 Group’s attack on the assembly buildings was hampered by a strong cross wind but substantial damage was inflicted and this left only 5 and 6 Groups to complete the operation by bombing the experimental site.

‘It was inconceivable that the site could ever operate again’ recalled Eddie Wheeler ‘and at least we had gained valuable time against V1 and V2 attacks on London and our impending second front assault forces. This raid probably gave us our most satisfaction against all other targets attacked.’

On 26 August Albert Speer called a meeting with Hans Kammler, Dornberger, Gerhard Degenkolb and Karl Otto Saur to negotiate the move of A4 main production to an underground factory in the Harz mountains. Another reaction to the aerial bombing was the creation of a back-up research test range near Blizna, in southeastern Poland. Carefully camouflaged, this secret facility was built by 2,000 prisoners from the Pustkow concentration camp, who were killed after the completion of the project. ‘Armia Krajowa’ the Polish resistance movement, succeeded in capturing an intact V2 rocket there in 1943. It had been launched for a test flight, failed but did not explode and was retrieved intact from the River Bug and transferred secretly to London.