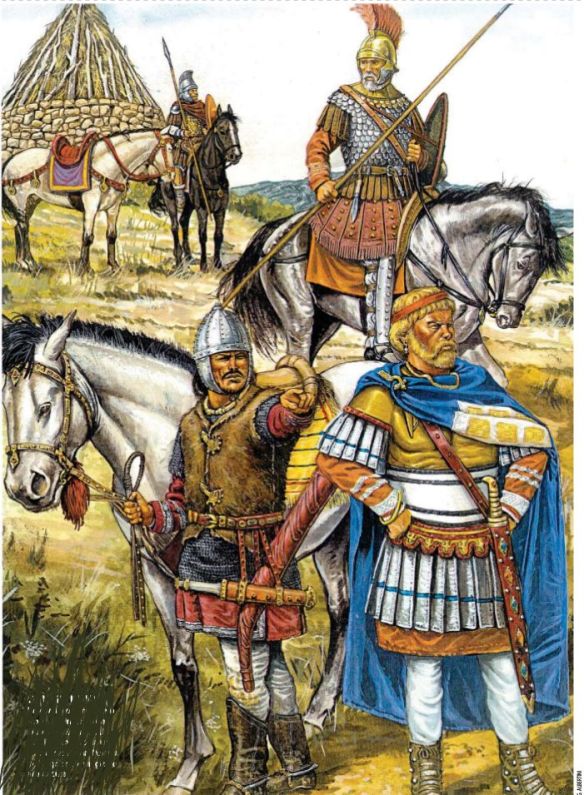

Aetius surveys the Catalaunian fields. Aetius was still generalissimo of the west, and as we know from Merobaudes’ second panegyric, he had been anticipating the possibility of a Hunnic assault on the west from at least 443.

Roman general, sometimes known as “the last of the Romans,” who spent most of his military career in Gaul temporarily delaying the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire. Born around 391 in Durostorum (Silistra) in Moesia in present-day northern Bulgaria, Flavius Aetius was the son of Gaudentius Aetius whowas Comes Africae and then Magister Militum per Gallias, and was Gothic. . Following the death of his father in a mutiny, young Aetius was sent as a hostage to Alaric from 405-408, and then to Uldin and Charaton from 408 to an unknown date, but stated to be longer than his stay with Alaric, so 411 or later..

Aetius was sent to recruit Huns by Ioannes in 424, not 412, and upon his return the usurpation was over, so Aetius bargained for his (now dead) father’s posting of Magister Militum per Gallias, becoming commander of the Roman cavalry in Gaul in 425 under new western Roman emperor Valentian III (r. 425–455). Aetius defeated Visigothic king Theodoric of Toulouse at Arles in 425. He was one of three major generals – the third was Flavius Constantius Felix, who held the highest posting (Magister Utiusque Militiae) and instigated the war with Boniface from 427-429, at the end of which it was revealed that Felix had deceived Placidia and Boniface. Aetius had him hung by the army in 430 and took his posting. Named assistant commander in chief of the army in the west, he was accused of murdering his superior and was thought by some to be harboring imperial ambitions.

Refusing to accept disgrace, Aetius invaded Italy only to be defeated at Ravenna in 432 by his rival Bonifacius, who was mortally wounded. Forced to flee, Aetius, upon requesting Hunnish support in 433, did not go to Attila as Bleda and Attila are stated to have succeeded after the death of Rua, which occurred some time between 434 and 439.

One of the keys to Aetius’s success was his ability to play one group of barbarians against the other and build coalitions of forces. An uprising of the Burgundians occurred from 435-436, and the defeat of the Goths outside Narbona was performed by Litorius in 436, who had returned from campaigning against the Armoricans., an event celebrated in the epic poem Nibelungenlied (Song of the Nibelungs). In 435 and 436 he defeated Theodoric and the Visigoths twice, at Arles and at Narbonne. In 442 Aegius concluded peace with Theodoric and the next year moved the Burgundians from Worms to Savoy. Aetius then turned to the Franks, defeating them in 445.

In 451 he assembled a coalition of Romans, Franks, and Visigoths to defeat an invasion of Gaul by the Huns under Attila in battle at at Châlons, quite possibly saving Western civilization in the process, as Attila then withdrew back across the Rhine. In 451 he assembled a coalition of Romans, Franks, and Visigoths to defeat an invasion of Gaul by the Huns under Attila in battles at at Châlons, quite possibly saving Western civilization in the process, as Attila then withdrew back across the Rhine.

Aetius, who had at one time allied with Hun tribes for his own purposes, to the defence of Gaul. The common threat also brought the local king of the Visigoths, Theodoric, together with his eldest son Thorismund, into alliance, along with the Burgundians and Bagandae from eastern Gaul, who had already suffered at the hands of the Huns, and the Alans from the west. The allied armies numbered perhaps 30–50,000, though the exact numbers are not known. Attila’s host has been estimated at around the same size, but both figures are largely guesses. The Huns fought with their traditional cavalry armed with bows and swords and lassos, but also fought on foot with swords and axes. The Roman–Visigothic army had heavy cavalry, light cavalry, traditional Roman infantry with sword and javelin, and more lightly armed troops from the non-Roman allies. Aetius, who as a hostage with the Huns many years before had developed a shrewd understanding of their battle tactics, opted for a formation that put his weaker forces in the centre and his stronger forces on the wings. Attila adopted the contrary pattern, with his stronger veterans in the centre, but more vulnerable forces on either side.

It is thought that the battle began in the early afternoon and went on to a bloody crescendo at dusk. The combat hinged around a low ridge overlooking a sloping plain. The Roman army attacked it from the right, the Huns from the left, but the fight for the crest of the ridge fell to the Roman side, aided by a flanking attack from the Visigothic cavalry. The Huns were pushed back on their flanks and finally broke back down the slope. Attila is supposed to have admonished them to stand and fight: ‘For what is war to you but a way of life?’ They charged back up the slope but were always at a disadvantage. Bitter hand-to-hand fighting followed. The gore-soaked ground was supposed to have turned a small river running across the fields red with blood. Theodoric was killed in the mêlée. At the end of the battle Aetius was unable to find his camp, so he stayed with his Gothic allies overnight. But the clear result was the retreat of the Huns, worn down by the long battle, who returned to their camp of encircled wagons and waited to see what the following day would bring.

This was indeed a historic moment and it was achieved by a mixed army of men whose individual motives and fears explained their courageous stand against the waves of Hun cavalry and foot soldiers. They showed that the Huns were not invincible, though it had been an unfamiliar contest for Attila, who preferred weaker opponents or a battle on the run rather than one against a large, disciplined army. The memory of that victory lingered on in European folklore as the moment when Europe was saved again from the domination of Asia. In truth, Attila was followed over the centuries by waves of other nomadic invaders from the east, but nothing has stayed in the collective consciousness of the West so firmly as the turning of the tide against the Huns.

Over the days that followed the battle, the Visigoths and Romans broke camp and left, allowing Attila the opportunity to take his battered army swiftly back to Hungary. According to the best-known account, he died two years later from a nosebleed that choked him to death after a night of heavy drinking.

In 454 Aetius, confident of his own position, offended Emperor Valentinian III by demands in the course of an audience in the imperial palace in Rome. Valentinian drew his sword and stabbed Aetius, whereupon other members of the court followed suit. Once Aetius had been killed, members of his entourage in Rome were summoned to the palace and were murdered one by one. It was said that in this deed Valentinian had “cut off his left hand with his right,” for Aetius was the last great Roman imperial general. In 476 the Western Roman Empire passed under barbarian control.

LINKS

Placidi Valentiniani Felices Guide to 5th Century Roman Military Equipment

Placidi Valentiniani Felices

Aetius Attila’s Nemesis

Ian Hughes