SIZE AND ORGANIZATION

As with most Confederate armies, the organization of the Army of Tennessee varied. At the height of its strength prior to Chickamauga, in September 1863, it numbered 48,000 infantry and 15,000 cavalry. The army consisted of three infantry corps and one of cavalry.

In November 1862 I Corps was created under the command of Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk. He was succeeded by Major General B. F. Cheatham, Lieutenant General William J. Hardee, and Major General Patrick Cleburne. A part of III Corps was added to I Corps on October 31, 1863; the Reserve Corps was added to it on November 4, 1863; and on April 10, 1865, as the war was rapidly winding down, all forces remaining in Georgia were added.

April 1862 brought the creation of II Corps at Corinth, Mississippi, consisting of two divisions, one under Jones Withers, the other commanded by Daniel Ruggles. This corps had the distinction of being the largest in the CSA at the time of its formation, at 22,000 men. It was initially commanded by Braxton Bragg. When Bragg was promoted to commanding officer of the Army of Mississippi effective May 7, 1862, William J. Hardee assumed command of the Army of Tennessee, followed by John Breckenridge. Breckinridge was relieved after the struggle for Chattanooga, and John Bell Hood became commanding officer. After Hood was elevated to command of the Army of Tennessee during the Atlanta Campaign, John C. Breckinridge and then Alexander P. Stewart assumed command of II Corps.

Five commanders had a turn leading III Corps: William J. Hardee, Edmund Kirby Smith, Simon Bolivar Buckner, Leonidas Polk, and Alexander P. Stewart. It was formed when Major General Hardee’s division, originally part of the Central Army of Kentucky, was consolidated with other Confederate forces prior to the Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862). With only 6,789 men, it was the smallest of the corps in the Army of Tennessee at that point but grew to 26,500 men late in 1862. Not fighting in a major battle, the corps was soon broken up, only to be reconstituted during the Siege of Vicksburg (May 18–July 4, 1863), when it became 33,000 strong. Disbanded in the course of the siege, it was reassembled for operations designed to lift the siege, reaching a strength of 42,000 before it was again dissolved after the fall of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, with portions going to II Corps. In the campaign culminating in the Battle of Chickamauga (September 19–20, 1863), III Corps was reconstituted under Stewart, only to be broken up after the battle. Under Polk, III Corps was assembled a final time following the Battles for Chattanooga (November 23–25, 1863).

Although Forrest’s Cavalry Corps is the cavalry formation most closely associated with the Army of Tennessee, it was not the only cavalry unit to fight as part of it. On January 22, 1863, Major General Joseph Wheeler was given command of all the cavalry in Middle Tennessee, and in March the cavalry divisions in the Army of Tennessee were designated as two corps, one under Wheeler and the other under Earl Van Dorn. Wheeler’s Corps, at its height, consisted of 12,000 men and was active (often in diminished numbers) throughout the war. Van Dorn’s Corps was activated on March 16, 1863, numbering 8,000. When Van Dorn was murdered on May 7 of that year by a physician who claimed the general was sleeping with his wife, command of his cavalry was assumed by Nathan Bedford Forrest. It served with the Army of Tennessee until early in the Chattanooga Campaign, when army commander Braxton Bragg ordered Forrest to transfer most of his corps to Wheeler’s Corps. Forrest essentially mutinied, threatening to kill Bragg if he dared give him further orders. At this, President Davis transferred Forrest to Mississippi to form a new cavalry corps.

MAJOR CAMPAIGNS AND BATTLES

KENTUCKY CAMPAIGN (JUNE–OCTOBER 1862)

In August 1862 Braxton Bragg invaded Kentucky with his Army of Mississippi (predecessor to the Army of Tennessee). His objective was to rally Southern supporters in the border state to join the Confederacy, thereby drawing the Union’s Army of the Ohio (Don Carlos Buell) away from the Eastern Theater. He concentrated in Chattanooga, Tennessee, whence he moved north into Kentucky, coordinating his advance with that of Edmund Kirby Smith, who was starting out from Knoxville.

At the Battle of Munfordville (September 14–17, 1862, Kentucky; Confederate victory), Bragg captured some 4,000 Union soldiers, then advanced to Bardstown and participated in the inauguration of a provisional Confederate governor (October 4, 1862). The Army of Mississippi engaged the Army of the Ohio at the Battle of Perryville (October 8, 1862, Kentucky; Confederate strategic defeat). Had Bragg pressed the fight, he might have achieved victory, but he vacillated and then retreated through the Cumberland Gap to Knoxville.

The Kentucky Campaign collapsed but did succeed in pushing Union forces out of northern Alabama and much of Middle Tennessee. Bragg’s unsure leadership provoked protest and near-mutiny among his subordinates.

BATTLE OF STONES RIVER (DECEMBER 31, 1862–JANUARY 2, 1863)

Bragg’s Army of Tennessee engaged William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland just outside of Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Bragg took the initiative, mauling Rosecrans’s right flank. Unfortunately for Bragg, the false report of Rosecrans’s withdrawal kept Bragg from moving to exploit his gains. By January 2 it became apparent that Rosecrans was holding his ground. Bragg therefore ordered Breckinridge to attack the Union left late in the afternoon. The Confederates came close to a breakthrough, but Union artillery disrupted the assault, resulting in a tactical draw—until Union reinforcements forced Bragg to retreat. Rosecrans thus gained a strategic victory.

CHICKAMAUGA CAMPAIGN (AUGUST 21–SEPTEMBER 20, 1863)

After the successful Tullahoma Campaign, Rosecrans continued the Union offensive, aiming to force Bragg’s Confederate army out of Chattanooga. Through a series of skillful marches toward the Confederate-held city, Rosecrans forced Bragg out of Chattanooga and into Georgia. Determined to reoccupy the city, Bragg followed the Federals north, brushing with Rosecrans’s army at Davis’s Cross Roads. While they marched on September 18, Bragg’s cavalry and infantry skirmished with Union mounted infantry, who were armed with state-of-the-art Spencer repeating rifles. Fighting began in earnest on the morning of the 19th near Chickamauga Creek. Bragg’s men heavily assaulted Rosecrans’s line, but the Union line held. Fighting resumed the following day. That afternoon, eight fresh brigades from the Army of Northern Virginia under General James Longstreet exploited a gap in the Federal line, driving one-third of Rosecrans’s army, including Rosecrans himself, from the field. Only a portion of the Federal army, under General George Thomas, staved off disaster by holding Horseshoe Ridge against repeated assaults, allowing the Yankees to withdraw after nightfall. For this action Thomas earned the nickname the “Rock of Chickamauga.” The defeated Union troops retreated to Chattanooga, where they remained until late November.

CHATTANOOGA CAMPAIGN (SEPTEMBER 21–NOVEMBER 25, 1863)

Grant’s first priority after he was assigned to command the Union’s western armies in October 1863 was to lift the Confederate siege of Chattanooga and the Army of the Cumberland that was holding the city. He brought in Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee, and Bragg now found his Army of Tennessee fighting a heavily reinforced Union army. The Battles for Chattanooga began on November 23 when Union forces over-ran Orchard Knob and continued with Lookout Mountain (November 24–25) and Missionary Ridge (November 25). The breakthrough sent Bragg’s army into a withdrawal that threw the door open to a Union invasion of the Deep South. It was the Army of Tennessee’s most consequential defeat.

ATLANTA CAMPAIGN (MAY 7–SEPTEMBER 2, 1864)

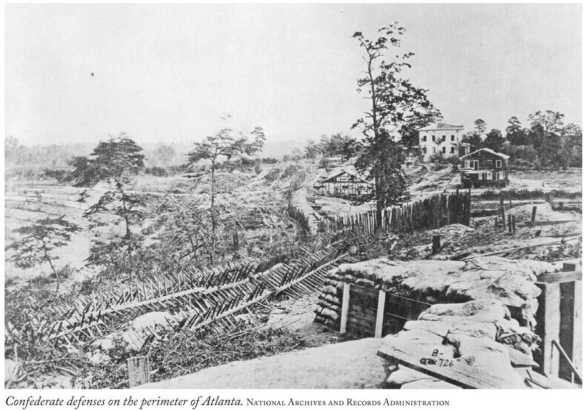

The Army of Tennessee was under the command of Joseph E. Johnston during the Atlanta Campaign and consisted of three corps—I Corps, designated Hardee’s Corps; II Corps, designated Hood’s Corps; and III Corps, designated Polk’s Corps—in addition to a cavalry corps, designated Wheeler’s Corps, and an artillery reserve under Brigadier General Francis A. Shoup. Throughout the first phase of the campaign, Johnston responded to Sherman’s attacks by steadily falling back on the city. After the Battle of Pace’s Ferry (July 5, 1864), President Jefferson Davis replaced Johnston with the aggressive Hood, whose attempts at counterattack, from the Battle of Peachtree Creek (July 20, 1864) through the Battle of Jonesborough (August 31–September 1, 1864), failed to prevent the fall of Atlanta and the surrounding area.

BATTLE OF FRANKLIN (NOVEMBER 30, 1864)

Defeated at Atlanta, Hood and the Army of Tennessee marched west while Sherman, leaving an occupying force in Atlanta, commenced his March to the Sea. While Sherman marched east, he assigned the Army of the Ohio (John M. Schofield) and the Army of the Cumberland (George H. Thomas) to deal with Hood in Tennessee. On November 29, 1864, Hood engaged Schofield at Spring Valley, intending to destroy his outnumbered forces. He failed, and Schofield advanced to Franklin, not far from Nashville. On November 30 Hood made a reckless assault against Schofield’s well-entrenched army and was repulsed with the loss of more than 6,000 men killed and wounded. Six Confederate generals died in the battle.

BATTLE OF NASHVILLE (DECEMBER 15–16, 1864)

Bloodied but unbowed, the Army of Tennessee (numbering about 30,000 at this point) advanced on Nashville, which was defended by some 55,000 men of Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland. Despite the odds, Hood positioned his army south of the city on December 2. After a delay caused by winter weather, Thomas attacked on December 15, shattering the Army of Tennessee by the next day.

CAROLINAS CAMPAIGN (FEBRUARY–MARCH 21, 1865)

The Battles of Franklin and Nashville decimated the Army of Tennessee, but, once again under the command of Joseph E. Johnston, it marched toward the Carolinas. Johnston’s objective was to consolidate with the remaining forces under Beauregard, Hardee, and Bragg to arrest Sherman’s devastating advance through the Carolinas. The Army of Tennessee fought at Aiken (February 11, South Carolina; Confederate victory), Monroe’s Crossroads (March 10, North Carolina; inconclusive), and Averasborough (March 16, North Carolina; inconclusive) before the final showdown at Bentonville (March 19-21, North Carolina; Union victory). Johnston’s battered army fought gallantly, doing great damage to Union general O. O. Howard’s XIV Corps before Union counterattacks arrested Johnston’s offensive thrust. The Army of Tennessee and units consolidated with it retreated toward Raleigh. Sherman failed to pursue. For his part, however, Johnston believed the Army of Tennessee and the rest of the CSA were finished. He held a grand review of his forces on April 6 at Selma, North Carolina, and surrendered to Sherman on April 26.