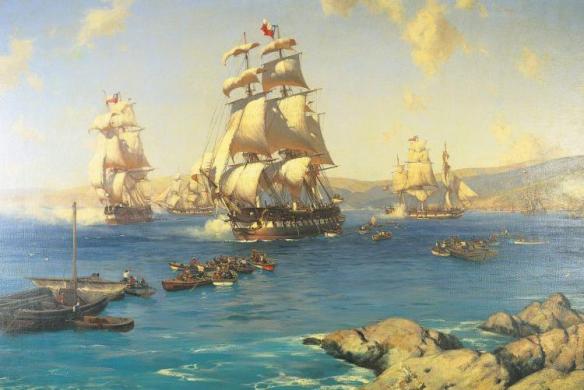

Painting of the First Chilean Navy Squadron commanded by Cochrane

Naval power played almost no role in the initial fighting after the revolutions of 1810. Local patriots engaged Spanish garrisons and local royalists in relatively small battles. Spain’s makeshift naval presence included armed merchantmen and privateers commissioned by the viceroy in Peru, a royalist stronghold; several of the new republics likewise issued letters of marque and armed some merchant vessels. The first naval action on the Pacific coast came in May 1813, when the Peruvian corsair Warren blockaded Valparaiso, a port defended by the Chilean armed merchantmen Perla and Potrillo. Spanish merchants in Valparaiso persuaded the officers and men of the Perla to defect to the royalists, and at the onset of the ensuing battle the Perla joined the Warren in forcing the Potrillo to surrender. Spanish forces then occupied Valparaiso and used it as a base to supply their reconquest of Chile. In exile across the Andes in Argentina, bitter Chilean patriots were impressed with their need for a navy and convinced that, to operate it, hired foreigners would be more trustworthy than veterans of the Spanish navy or merchant marine.

The Argentinians subsequently commissioned a small navy led by William Brown, a former officer of the British navy. In the summer of 1815-16 Brown took two corvettes and two smaller warships around Cape Horn and up the Pacific coast, attacking Callao and Guayaquil. He did little real damage, but did demonstrate the vulnerability of Spanish commerce and communications. In the summer of 1816-17 generals José de San Martin and Bernardo O’Higgins crossed the Andes with an Argentinian-Chilean army that defeated the Spanish at Chacabuco in February 1817, opening the way for the restoration of the republic in Chile under the presidency of O’Higgins. On the field at Chacabuco, O’Higgins remarked that “this triumph and a hundred more will be insignificant if we do not control the sea.” He soon sent agents to Britain and the United States, countries where the return to a peacetime footing after 1815 left naval personnel seeking employment abroad.

By 1818 hundreds of foreign seamen had entered Chilean service, many of them aboard ships purchased for the new navy. These included a corvette, two brigs, and the former British East Indiamen Cumberland and Windham, refitted as the 60-gun ship of the line San Martin and 46-gun frigate Lautaro, respectively. To command the navy a Chilean agent hired Thomas, Lord Cochrane, later 10th Earl of Dundonald, a decorated veteran British officer living in exile in France after being disgraced in a stock market scandal in 1814. Cochrane left for Chile in August 1818, three months after the former Russian frigate Maria Isabel left Spain for Chile at the head of a force including eleven transports carrying 2,000 troops. The Chileans received word that the Spanish reinforcements were on the way and resolved to interdict their convoy rather than wait for Cochrane to arrive. Command of the Chilean squadron went to Manuel Blanco Encalada, a 28-year-old artillery officer from Buenos Aires who had served the previous seven years in the armies of Argentina and Chile. O’Higgins appointed him because he had been an ensign in the Spanish navy for four years before that, and thus had more naval experience than any other patriot officer. In October 1818 he left Valparaiso with the five warships, to search the seas for the approaching Spanish force. The Maria Isabel managed to evade him, making it through to the port of Talcahuano with two transports, only to be trapped there on 27 October by Blanco’s flagship San Martin, to which the Spanish frigate surrendered after a brief duel. The remaining Spanish transports were captured as they straggled in, completing the triumph.

Thus Chile was secure by the time Cochrane took over the navy, in December 1818, with the rank of vice admiral. Blanco agreed to become his subordinate as rear admiral, impressing Cochrane with his “patriotic distinterestedness” in the matter of command. They turned their attentions to an assault on royalist Peru, which had to be conquered to secure the independence of both Chile and Argentina. Because the coastal Atacama Desert separating Peru from Chile posed an obstacle more formidable than the Andes, naval power was essential to transport the patriot army northward for the attack. First, however, Cochrane had to establish Chile’s command of the sea off the western coast of the continent. In the summers of 1818-19 and 1819-20 he imposed blockades on Callao and seized Spanish-flagged ships on the high seas, using the captured Maria Isabel (renamed O’Higgins) as his flagship. But the Spanish were more afraid of the San Martin, the only ship of the line in the theater; they refused to come out of Callao to fight, even though the two navies had equal numbers of frigates and smaller warships. In May 1819 Spain dispatched two ships of the line and a frigate as reinforcements, but only the frigate made it to Callao. The leaky Alejandro I, formerly a Russian battleship, had to turn back to Cadiz, and the San Telmo was lost with all hands in a storm off Cape Horn. Further additions to the Chilean navy included a corvette built in the United States, two more brigs and a schooner. In February 1820 Cochrane briefly turned his attention to Valdivia, a Spanish outpost in southern Chile, which he captured with the O’Higgins, a brig and a schooner, in the process losing the brig.

A painting of the Capture of Valdivia in the Chilean naval and maritime museum

The invasion of Peru finally began in late August 1820. Cochrane, in the O’Higgins, led a force of one ship of the line, two frigates, one corvette, three brigs, and one schooner, escorting seventeen transports carrying San Martin and 4,000 troops. The fleet included every available Chilean warship less one corvette, which was deployed to keep watch over the last royalist stronghold in the south, the island of Chiloé. The Spanish squadron in Callao did nothing to challenge the Chilean landings. The frigates Prueba and Venganza departed before the invaders arrived, to avoid being blockaded, and the hopelessly outnumbered force they left behind suffered a crippling blow on 5 November 1820, when Cochrane captured the remaining Spanish frigate, the Esmeralda, in a bold raid on the harbor. The aggressive Cochrane clashed with the cautious San Martin throughout the campaign. Cochrane wanted the navy to assault Callao while the army marched on Lima, but San Martin preferred to negotiate his way into the Peruvian capital. The viceroy in Lima finally agreed to an armistice in April 1821, and three months later San Martin declared himself “protector” of an independent Peru.

Many years passed before Spain recognized the independence of any of the Latin American republics, and Cochrane correctly refused to consider the war ended, Rejecting San Martin’s offer to become admiral of a new Peruvian navy, he remained loyal to Chile and put to sea in search of the last significant Spanish warships in the eastern Pacific, the two frigates that had escaped capture at Callao the previous year. Several of Cochrane’s British officers and seamen declined to go with him and instead entered the service of Peru, in part because San Martin refused to pay them as long as they remained in Chilean service. After a pursuit of five months, ranging as far north as Baja California, in March 1822 Cochrane finally blockaded the Prueba and Venganza at Guayaquil. There the two frigates surrendered to local authorities loyal to San Martin and thus ended up in the Peruvian navy. The Prueba, renamed Protector, became the flagship of one of Cochrane’s former captains, George Martin Guise, now serving as Peruvian naval commander. Denied these ultimate prizes of war, in June 1822 Cochrane returned to Valparaiso with the remaining ships of the fleet. By then the Chilean navy showed the strains of years of continuous operations. The numerous desertions at the end of the campaign in Peru forced Cochrane to abandon the ship of the line San Martin, and a brig badly in need of repair was given up for lost. This left the fleet with a core of three frigates, three corvettes, and two brigs.