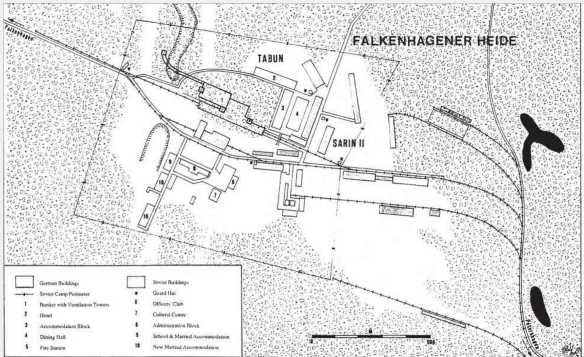

The factory had been built as the result of a decision made by the Wehrmacht’s Heereswaffenamt (Army Weapons Administration) back in 1938 to go in for the manufacture of Chlortrifluoride for the recently discovered nerve-gas TABUN. Chlortrifluoride, or N-Stuff, as it was called, is an aggressive, highly inflammable substance that needs very special handling. In order to remain perfectly dry, the factory needed a shell five metres thick to prevent any intrusion from the water table. It was envisaged that the whole production process would take place underground as far as loading the finished product in steel containers on railway wagons. However, it would take time to complete the construction of the bunker, for which it was stipulated that only German-born nationals could be employed, so some above-ground laboratories and plants were erected to enable the preliminary development of the manufacturing process from laboratory to factory-scale production. In fact the construction of the bunker was to take until 1943, a full five years to complete, one delaying factor being the difficulty of meeting the manpower requirements at the height of the war.

When Albert Speer became the Minister for Armaments and Munitions in 1943, he decided to implement the production of SARIN II, a later generation of nerve-gas, at the same site. The two products and those concerned with them were kept completely separate. A small satellite camp of the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp was set up that year in the woods north of the site, but whether the inmates were employed in the construction of the SARIN II installations, or used in the assembly of V-Weapons in part of the underground factory remains uncertain.

Considerable effort was given by the Germans to camouflaging the site from aerial observation. Transportation was by a special narrow-gauge track connecting with the main lines at Briesen. These tracks followed the contour of a new concrete road through the forest built to detour local traffic away from the site and were countersunk in the road surface to conceal their profile. Production also required a heavy consumption of electrical power, and immediate post-war maps show a line of overhead pylons stopping abruptly a considerable distance from the site. This clue to something unusual in the vicinity that would merit such a supply was later removed. During the war the Germans continued to rely on camouflage for the protection of the site and no anti-aircraft guns were deployed that might have attracted attention to it.

The upper level of the five-storey factory was concealed under a natural hill in such a way that a railway line ran right through it in a tunnel. Three ventilation towers projected above the hill below the height of the tops of the trees that covered it.

During the brief period the factory was operational, between October 1944 and February 1945, between twenty-two and thirty tons of Chlortrifluoride were finally produced. By this time the site was under SS control and it seems that V-Weapons were also assembled here. When the Red Army established bridgeheads across the Oder river at the beginning of February 1945, production was hastily abandoned and the satellite concentration camp disbanded.

Clearly the factory and site would have been stripped by the Soviets of everything removable in 1945 as part of their reparations scheme. Having no further interest in the site at that time, the Soviets handed it back to the local authorities and it was not until the 1950s that the Soviet Army returned to establish a unit there that had regular contact with the local residents. In this connection, it is believed that the principal communications facility for the Headquarters of the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany at Zossen-Wunsdorf was moved here following the Anglo-American spy tunnel intercept from the south-east corner of the American Sector of Berlin being discovered in April 1956.

Then in the 1970s work was begun on converting the factory into the GSFG command bunker. One of the ventilation towers was filled with filters for use in case of a biological attack, when the other two could be cut off. The railway tunnel was blocked off at either end and airproof personnel entrances installed incorporating a series of three massive steel doors about a metre wide, two metres high and half a metre thick. Between these doors were built decontamination facilities overlooked by control cubicles, and a hospital installed close behind.

Down below, the various production chambers were converted into the control bunker role with raised floors under the communications rooms allowing easy access for the technicians, a special wallpapered, self-contained suite for the C-in-C, and other facilities for the senior officers. The soldiers appear to have been allocated collapsible bunks hinged to the corridor walls, denoted by painted numbers. The main operations room had a false ceiling reducing its original height.

From interpreters who took part, it is known that Warsaw Pact exercises were conducted here, and from 1988 onwards helicopters were heard landing at the site.

The Soviets left the original production structures alone, apart from two halls that they used for basketball and the original accommodation block. But they did build officers’ quarters, a large accommodation block and an hotel with a separate, communal mess hall, all within the outline of the original structures. They also built a cultural centre, an officers’ club, family accommodation and a school, and even some new family accommodation blocks immediately before their departure in 1992. Had it not been for the Four plus Two Agreement, it seems that the army of the new Russian Federation had been prepared to stay and maintain its capacity for a nuclear or biological strike.

[Sources: Seelow Heights Museum and Dr Heini Hofmann of Falkenhagen]