James III of Scotland did not enjoy a popular reign. His difficulties with the magnates were not resolved after the cull on Lauder Bridge and festered till a further and final confrontation in the campaign and Battle of Sauchieburn on 11 June 1488, when the king was assassinated in murky circumstances following the rout of his forces. His son’s biographer, Norman Macdougall, has observed that, during James III’s reign, naval hostilities continued despite any prevailing truces:

As the Treasurer’s accounts are lacking for almost all of James III’s reign, these examples may not give a fair balance. What they show clearly, however, is that the principal menace to Scots shipping in the North Sea was the hostility of the English. For sea-warfare, even in time of truce, tended to form a category of its own.

The plain fact is that sea-raiding and privateering were highly profitable activities for successful captains, and the niceties of diplomacy could not be allowed to intrude upon such lucrative enterprise. At Bamburgh on the Northumbrian coast, Bishop Kennedy’s fine ship Salvator ran aground in March 1473 and was relieved of her cargo by James Ker, despite his Teviotdale name, an Englishman. It required negotiations spanning a year and a half before James III, who may have been a stakeholder in the vessel, managed to lever any compensation. Gloucester’s cog Mayflower had taken Yellow Carvel, a ship later to be associated with Andrew Wood of Largo. Sir John Colquhoun of Luss was also despoiled of shipping by Lord Grey. John Barton, brother of Andrew, had one of his vessels taken off Sluys by Portuguese pirates, who stripped the valuable merchandise and murdered a number of those on board.

In October 1474, James had succeeded in brokering a rather flimsy alliance with Edward IV, which finally broke down six years later, and the war of 1481–1482 saw a considerable amount of action at sea. In this the advantage lay heavily with the English. In 1481, Lord John Howard took his squadron into the Firth of Forth and secured a number of valuable prizes, eight Scottish vessels, taken from Leith, Kinghorn and Pittenweem. He then took up Blackness, which was thoroughly spoiled and torched, capturing another and larger vessel. This aggression did not go unopposed, for Andrew Wood led a flotilla which engaged the English, apparently gave a very good account of themselves and inflicted numerous losses. Next year, to support Gloucester’s invasion, Sir Richard Radcliffe, an intimate of the duke’s who was to rise in his administration, led a second expedition, probably placing his flag on the capital ship, Grace Dieu. He was able to occupy Leith and contributed significantly to the English victory on land and the recovery of Berwick – the final time that much beleaguered town was to change hands. Dunbar, an important bastion on the coast of Lothian, was handed over to the English in 1483 by James’s traitorous sibling the Duke of Albany and remained in their possession for a couple of years. Being a coastal fortress, the English could rely on their maritime supremacy to facilitate re-supply.

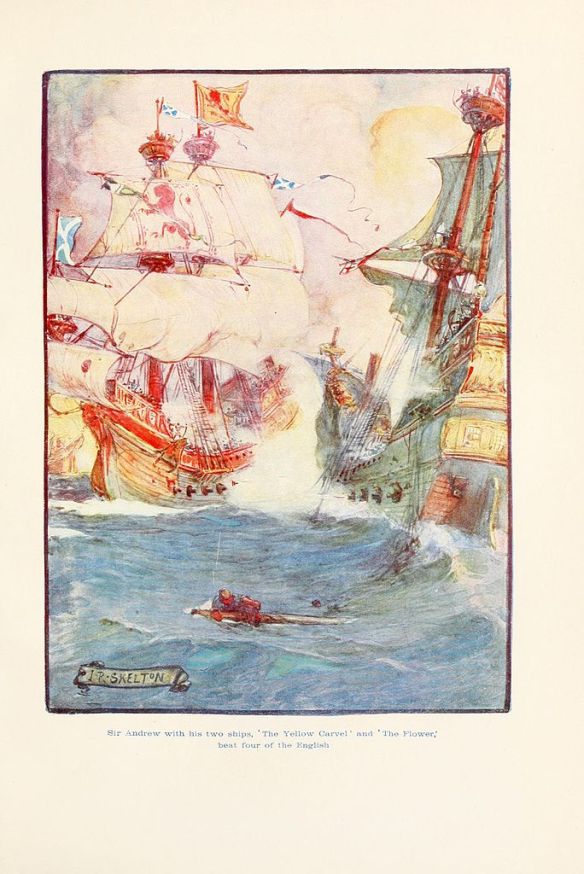

Andrew Wood had been rewarded for his zeal in opposing Howard with the feu-charter of Largo, granted in 1483. The king needed Sir Andrew within his affinity in the campaign which led up to the king’s defeat and subsequent death in the spring of 1488. It was Wood’s ships, Yellow Carvel and Flower, which twice transported royal forces across the Firth of Forth and carried the battered survivors back. James may well have been in flight towards these ships when he was overtaken and killed. Both of Sir Andrew’s ships were sizeable vessels of around 300 tons, and he was soon in action again against the English when, in 1489, his squadron took on five English raiders and captured them all in a brisk engagement off Dunbar. Wood was well rewarded for his victory, but Henry VII resented the humiliation of so sharp a reverse and commissioned Stephen Bull, an experienced mariner who commanded three competent vessels, to take up the gauntlet.

Bull took his ships into the Firth of Forth, believing, correctly, that Wood was beating back from Flanders and keeping his squadron well hidden in the lee of the Isle of May. To identify his prey, he kidnapped local fishermen who, when sails were sighted, were obliged to climb to the topmast and identify the vessels. At first, the locals temporised but, with the incentive of their release dangled, confirmed the ships were indeed Yellow Carvel and Flower. Confident of success, having numbers and weight of shot on his side, Bull broached a cask and offered his officers an additional stimulus before engaging. Undeterred by the sudden ambush, Wood cleared for action. He was surprised, outnumbered and outgunned; like his opponent he broke out the grog before the great guns thundered. With the wind steady from the south-east, the longer English guns had the advantage. Wood then beat to windward before closing the range to unleash his own broadside.

The fight which followed was both long and hard. In the constricted waters of the Firth there was little scope for extensive manoeuvring and the battle became a slogging match. Both sides sought to grapple and board, pounding each other beforehand. Amidst shrouds of foul, sulphurous smoke, seamen strove to bring the opposing vessels together, cloying air quickened by the rattle of musketry, the crash of spars and rigging as round shot tore through sails and cordage.

Battle continued all day, the combatants, like punch-drunk fighters, lurching into the open sea. Newer weapons, ordnance and handguns, were deployed alongside crossbows and broadswords. Guns added to the demonic fury of battle with their diabolical roar and the filthy, sulphurous smoke they belched out, vast clouds of the stuff, whipping and eddying in the breeze, one minute obscuring the combatants, then lifting as though with the parting of a veil. As the ships closed to grapple and board, the marines spat bolts and leaden balls from handguns Then, it was down to hand strokes. Knots of fighters boiled over gunwale and deck, screams and shouted orders bellowed in the dense-packed melee. No one had anywhere to run; axes, mallets and the lethal thrust of daggers competed in the stricken space. Darkness brought a brief lull; shattered masts and rent sails were cut free and either cobbled together or ditched overboard. Decks were littered with debris from the fight, gunwales, in several instances, awash with gore and spilt entrails. In the quiet hours, many a man slipped away and was quietly heaved towards a watery grave.

Next day, trumpets sounded and the great guns thundered again as battered vessels rejoined the fight. As Wellington would have observed, it was a very close run thing. Losses and damage were considerable on both sides, but it was Bull’s Englishmen who struck their colours. A crowd of Scots had dashed along the shoreline as the battle reached the mouth of the Tay, cheering on the home side! Sir Andrew had wisely stayed to windward, herding the Englishmen towards the Fife shore. Unaware of the risk, till too late, all three of Bull’s ships ran aground. The fight was over, the stranded keels boarded and towed in triumph to Dundee. James, delighted with his victory, could afford to be magnanimous, and the survivors were repatriated, but only after a spell as forced labour working on coastal defences! Wood survived into a comfortable retirement and even ordered the construction of a canal between his fine house and the parish church so that, as he journeyed to Mass he might be conveyed in his barge in a manner befitting so venerable a sea-dog.