They may have been the ‘Good Spirit’ islands mentioned by Ptolemy; they were certainly referred to by the fifth-century Chinese Buddhist I’Tsing, while Marco Polo, passing within sight in 1292, called them the ‘Angamans’ and said that the natives were cannibals with the heads of dogs. Nicolo dei Conti translated their name as ‘Islands of Gold’, although it probably derives from the monkeys which populated the forests. The Andaman Islands were the epitome of tropical paradise: the tips of a range of submarine mountains scattered like a necklace with 204 jewels across almost 2,500 square miles of the Bay of Bengal. Their countless natural harbours and rugged inlets were laced in turn with dazzling coral, while dugong and turtles swam the crystal waters. There were mangrove swamps, hills gashed by narrow valleys, forests of valuable redwood. At the start of the nineteenth century the islands lay on the main trade routes and offered shelter from the cyclones which lashed the Bay but never seemed to touch the islands.

The native people were largely untouched by the civilizations with which they came into contact. They had a policy of killing all foreigners. The people traced their blood lines to the pygmies of the Philippines and the Semang of Malaysia. They were hunters and gatherers, never farmers, on rocky outcrops where irrigation was unheard of. They fished from canoes with nets and four-pronged arrows. Their weapons were made of shell and broken shards of iron collected from shipwrecks. Sailors, merchants and explorers noted their ferocious hostility: hostility that was created, not inherent. Conti and Cesare Federici, who visited the islands in 1440 and 1569 respectively, wrote of peaceful natives in canoes. But hideous raids by Arab slave traders changed all that. The coastal tribes, who greeted strangers with simple gifts, were virtually wiped out. The inland Jarawa tribes were also friendly at first but clashed with foreign sailors who accused them of theft, a concept alien to tribes who regarded property as communal. A later British ambassador, M.V. Portman, said: ‘It was our fault if the Jarawas became hostile.’ An early incident on Tilanchong illustrates this point. In 1708 a vessel commanded by Captain Owen was shipwrecked and the crew ferried to nearby islands by courteous and kindly natives. Captain Owen put down a four-inch knife he had saved and it was picked up by an islander. Owen snatched it back, kicking and punching the native. Hamilton’s Voyages records: ‘The shipwrecked men could observe contention arising among those who were their benefactors in bringing them to the island . . . next day, as the captain was sitting under a tree at dinner, there came about a dozen of the natives towards him and saluted him with a shower of darts made of heavy wood, with their points hardened in the fire, and so he expired in a moment.’ His crew, however, were protected and given two canoes with water and food. They were told not to return. One canoe, with three men on board, survived the journey.

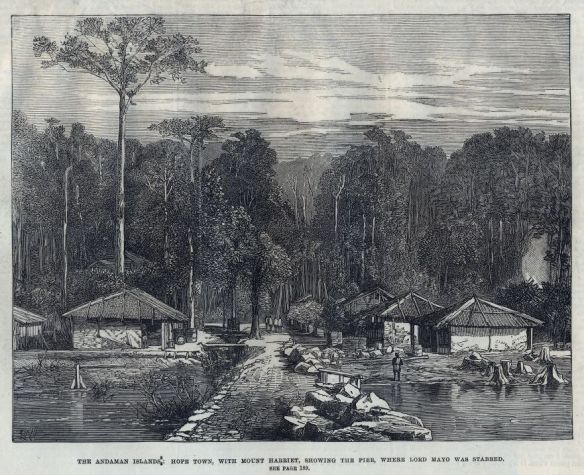

In 1789 Captain Archibald Blair had established a penal colony for prisoners from Bengal at Port Blair on Chatham Island. Two years later, under Admiral Sir William Cornwallis, it was transferred with a naval arsenal to Great Andaman. This proved too costly in both cash and lives – most prisoners and many guards died quickly of tropical diseases – and it was scrapped in 1796. The local population did not welcome strangers any more. In 1844 they killed the stragglers from the troopships Briton and Runnymede, which were driven ashore in a gale. Attacks on shipwrecked crews and the huge numbers of prisoners taken during the Indian Mutiny of 1857 pushed the British into establishing a settlement and another convict colony close to the original site at Port Blair. Ravaged by sickness, many died before swamp reclamation created healthier conditions. During the early years deportation to the Andamans was considered a death sentence.

The English tried to deal with the war-like Jarawas by arming the remnants of the coastal tribes, the Arioto, with firearms. Given such unique power they began to slaughter every Jarawa they could find. Portman wrote: ‘On our arrival the Jarawas were quiet and inoffensive towards us, nor did they even disturb us, until we took to constantly molesting them by inciting the coastal Andamanese against them.’

In 1867 some of the crew of the vessel Assam Valley were reported missing and captured by natives on Little Andaman Island. A detachment of the 2nd Battalion, 24th Regiment, South Wales Borderers, was dispatched on board the Arracan to find them.

#

The 24th Battalion had spent nearly six years in Mauritius, enjoying bathing, boating, cricket and local hospitality under balmy skies, before being sent to Rangoon. Three officers and 100 men were sent from there to the Andaman Island. Among them was a 26-year-old Canadian medical officer and four privates who were to join the most distinguished roll call in military history – the company of VC-holders.

Assistant-Surgeon Campbell Mellis Douglas, himself the son of a doctor, was born at Grosse Île, Quebec, and had been attached to the 24th in Mauritius. The privates, three of them Irish, were also in their twenties. David Bell, from County Down, had enlisted at Lisburn seven years before; William Griffiths, a County Roscommon man, had previously been a collier; and Dubliner Thomas Murphy had worked as a cloth dresser before enlisting. The fourth private, James Cooper from Birmingham, was illiterate when he signed up; he was the son of a jeweller and a stay-maker.

Shortly before the Andaman expedition Douglas, an accomplished boatman, had prepared a boat for entry into a regatta at Burma. The crew he trained for the event proved so strong that after winning the first race their boat was excluded from the competition to give others a chance. The names of his crew are not recorded but, given the later events, it is likely they included the Irishmen and the Brummie.

On 17 May 1867 the steamer Arracan reached Little Andaman, buzzing with rumours that the missing crew had been butchered by cannibals. On arriving at the scene of the alleged massacre, two boats were filled with armed soldiers and rowed inshore under the command of Lieutenant Much.

The Regimental History records: ‘A heavy surf was beating but one boat’s crew waded ashore through deep water and began moving towards a rock where the massacre was believed to have occurred, the other boat moving parallel to cover their movements. As they advanced natives began to show themselves and let fly their arrows freely but could not prevent the party from reaching the rock and finding the skull of a European, when, as they had nearly exhausted their ammunition, the signal for recall was made. In trying to embark those ashore near the rock the shore party’s boat was upset, so the men started back towards the original landing place, en route discovering the partially buried bodies of four more Europeans.’ As the plight of the men on the beach became all too obvious, increasingly desperate efforts were made to reach them through the surf, first by boats and then by rafts from the Arracan. As more boats were battered to pieces Assistant-Surgeon Douglas and the four privates volunteered to man a gig to renew the attempt. Their first bid to get through the roaring surf failed when their little boat was half-filled with water. During another attempt Lieutenant Much and others were swept off a makeshift raft. A correspondent wrote: ‘While in this critical and very dangerous predicament Dr Campbell Douglas showed all the qualities of a real hero. Being an excellent swimmer, and possessing great boldness and courage, he swam after the drowning men. Twice was Lt Much . . . washed off the raft, and, while struggling in the rolling waves, Dr Douglas flew to his rescue, and brought him back safe to the raft.’ Chief Officer Dunn of the Arracan, confused and sinking, was also plucked to safety by Douglas, but Lieutenant Glassford was less lucky. The correspondent, writing for the Liverpool Gazette, added: ‘Dr Douglas, having struck his head against the rocks in diving after one and another of those he saved, felt himself confused and bruised, and his strength giving out. He could not follow Mr Glassford, who was carried some sixty or seventy yards away, and he was drowned. As night was rapidly approaching, the whole party had to make the most herculean efforts to save themselves from the risks and dangers which now beset them on every hand.’

On two occasions Douglas and his crew got through the surf and brought back seventeen men, ‘the whole shore party being thus rescued from the virtual certainty of being massacred and eaten by savages’. The Regimental History added: ‘The surf was running high and the boat was in constant danger of being swamped, but Assistant-Surgeon Douglas handled it with extraordinary coolness and skill and, being splendidly supported by the four men, who showed no signs of hesitation or uncertainty, keeping cool and collected. . . .’

The expedition, having discovered the fate of the missing Europeans, steamed away but the exploits of Douglas and his gallant crew reached the ears of the Commander-in-Chief in India, Sir William Mansfield. Hostile natives, though a threat during the early part of the incident, had not been evident when Douglas arrived on the scene but officers who were present, not least those who had been saved, wanted the rescuers awarded the highest honour. The newly created Victoria Cross was intended only for heroism in the face of the enemy, but the officers, and some newspapers, argued that the courage displayed in a boiling surf on a hostile shore was more than enough. A large factor was that very few Victorian Britons could swim and the sea was thus held in some terror. Luckily, an amendment in 1858 had made it possible for the Victoria Cross to be awarded for exceptional heroism far from the front line – Private Timothy O’Hea had previously won it for putting out a fire in an ammunition wagon in Canada.

On 17 December 1867 the War Office confirmed the queen’s decision to reward all five men with the Victoria Cross. The citation for each was identical: ‘For the very gallant and daring manner in which they risked their lives in manning a boat and proceeding through a dangerous surf to rescue some of their comrades who formed part of an expedition which had been sent to the island of Andaman, by order of the Chief Commissioner of British Burmah, with the view of ascertaining the fate of the commander and seven of the crew of the ship Assam Valley, who had landed there, and who were supposed to have been murdered by the natives.

‘The officer who commanded the troops on the occasion reports: “About an hour later in the day Dr Douglas and the four privates referred to, gallantly manning the second gig, made their way through the surf almost to the shore, but finding their boat was half-filled with water, they retired. A second attempt was made by Dr Douglas and party and proved successful, five of us being passed through the surf to the boats outside. A third and last trip got the whole party left on shore safe to the boats.”

‘It is stated that Dr Douglas accomplished these trips through the surf to the shore by no ordinary exertion. He stood in the bows of the boat, and worked her in an intrepid and seamanlike manner, cool to a degree, as if what he was doing then was an ordinary act of everyday life. The four privates behaved in an equally cool and collected manner, rowing through the roughest surf when the slightest hesitation or want of pluck on the part of any of them would have been attended with the gravest results. It is reported that seventeen officers and men were thus saved from what must otherwise have been a fearful risk, if not certainty, of death.’

The five were the first of the ‘Old Green Howards’ to receive the Victoria Cross and the last to win it anywhere away from battle. By 1904 the regiment had sixteen VCs to its credit, of which seven were famously won at Rorke’s Drift.

Assistant-Surgeon Douglas enjoyed a long and illustrious career. The Royal Humane Society awarded him a silver medal for the same act of heroism. He was Medical Office in Charge of the field hospital during the second Riel Expedition in 1885, during which he made an epic 200-mile canoe trip carrying dispatches. He wrote papers on nervous degeneration among recruits, and on military doctoring. His favourite recreation was, naturally, sailing. He reached the rank of Brigade Surgeon and married the niece of Sir Edward Belcher.

In 1895 he made a single-handed crossing of the English Channel in a 12-ft Canadian canoe. He also patented a modification to a folding boat which was later put into general use. He died, aged sixty-nine, at his daughter’s home near Wells, Somerset, on 31 December 1906. A painting displayed in the RAMC Headquarters on London’s Millbank shows him standing bravely on the bows of the rescue boat.

Less is known of the four privates. Thomas Murphy emigrated to Philadelphia and died in March 1900 aged sixty. James Cooper left the Army, although he continued in the Reserves, and followed his father’s trade as a jeweller. He died in Birmingham in August 1882. David Bell became a sergeant but was discharged in 1873. He was employed as a skilled labourer at no. 8 machine shop, Chatham Dockyard. He died, aged seventy-eight, in 1920 at Gillingham.

William Griffiths, still a private, was killed by Zulus at Isandhlwana on 22 January 1879. He was buried in a mass grave on the battlefield, far from the sound of pounding surf.