In 1940 the Wehrmacht had been the masters of the battlefield, and by 1944 the lesson in mobile warfare had been taken to heart by the Allies’ From their beachhead in Normandy, the Allies swept through northern France in a massive drive to the Rhine and the heart of German industrial power in the Ruhr; in the forefront of the drive were the Allied reconnaissance units, playing their parts in the campaign to end the war in Europe.

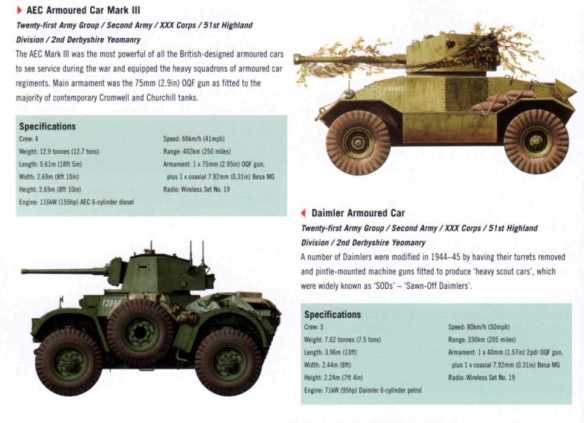

By June 1944 the organization of British armoured car regiments had settled down to a form involving a regimental headquarters and four ‘Sabre’ fighting squadrons. The equipment of these units varied somewhat from time to time and between regiments, but the basic personnel strength was about 650 men. The regimental headquarters had 12 or 13 Daimler or Humber scout cars, a Daimler armoured car, three Staghounds, four Humber AA armoured cars (later withdrawn) and some form of armoured command vehicle. The four Sabre squadrons each had its own squadron headquarters with one Daimler scout car and a Daimler armoured car, and three Staghounds There were five reconnaissance troops within the squadron, each with two Daimler scout cars and two Daimler armoured cars Within each squadron was a support troop with a single Daimler scout car and three White scout cars used as armoured personnel carriers To back up these units was a single support section-with two 75-mm (2.95-in) self-propelled guns These could be guns mounted on half-tracks or AEC Mk 3 armoured cars with the gun mounted in a large turret.

Losses in Normandy

After the D-Day landlngs, the Daimler scout car and the Daimler armoured car were the preferred equipment for the reconnaissance role, despite the general opinion that the Daimler armoured car was somewhat underpowered, For the scouting role the little scout cars were the preferred vehicles as they were easy to conceal, relatively quiet in use, and nippy and handy enough to move out of trouble when it was met. But in the early days of the Normandy campaigns the terrain was too enclosed and w-ell defended for scout cars to operate unhindered, and the German defensive tactics ensured a steady rate of attrition among the reconnaissance troops; one regiment, for example, lost 25 scout cars during the first month of the Normandy fighting. During the desperate slogging matches that marked the approaches to Caen the reconnaissance regiments could contribute little other than local battlefield reconnaissance, but once Caen was taken and the British and Commonwealth divisions moved forward the reconnaissance regiments once more came into their own.

The late summer of 1944 was marked by a series of rapid advances through the remains of the German armed forces in France. Throughout this time the armoured cars and scout cars ranged far and wide seeking out and passing back information, warning of defended positions and localities and generally attempting to move forward to maintain the vital momentum As in Normandy, much of the information was gained from the stealthy use of scout cars, to the extent that numbers of Daimler armoured cars had their turrets removed to reduce their height. These were known to the troops as SODs (Sawn Off Daimlers) and the loss of their 2-pdr (40-mm) guns was seen as no great problem as by 1944 the weapon was of very limited value, even with the addition of the Littlejohn adaptor to improve armour-piercing performance. If the scout cars did come up against opposition, the Daimler armoured cars with guns still mounted were called up to try to outflank and possibly to destroy the opposition so that the momentum of the advance could be maintained, If this were not possible the support section (or troop) could be called upon to add the weight of its 75-mm (2.95-rn) guns lf enemy armour was encountered the scout and armoured cars had no option but to report the fact and then do their best to get out of the way.

As the reconnaissance regiments moved north east out of France they entered the cluttered road network of Belgium, and were able to make good progress towards Brussels. The entry of the first armoured cars into Brussels was an occasion that none there would ever forget. On 3 September 1944 units of the Household Cavalry were the first to reach the capital and were greeted to a riotous welcome by cheering crowds, This created a state of euphoria that was soon dispelled by the failure of Operation ‘Market Garden’, when the same units that had entered Brussels could not reach the bridge al Arnhem. The advance towards the airborne units holding the Arnhem Bridge had to cross flat open country, where the only method of advance was along straight roads on which single German defensive positions were able to inflict delay after delay.

The armoured car units were unable to take much part in the battles to free the port of Antwerp, and by the end of 1944 the approaches to the Rhine and Saar rivers were marked by a series of set-piece battles, The Ardennes offensive mounted by the Germans was too far south to affect the British forces directly, but early in 1945 the Rhineland battles took place mainly in heavily wooded country, where the limited reconnaissance the scout cars were able to collect was of great value, By March 1944 the Allies were on the Rhine, and after the Rhine crossings the armoured cars once more spread their way across the north German plains towards the Baltic. In early April it was a reconnaissance unit that had the dubious distinction of being the first to enter the horrific concentration camp at Belsen. By this time German resistance had crumbled, and by late April the British and Commonwealth forces were approaching the Elbe. By early May armoured reconnaissance units had sighted the Baltic and on 2 May British and Soviet reconnaissance units met each other at Wismar.

It was all over soon after, The German surrender was signed at Lüneberg Heath and the reconnaissance regiments never did reach Berlin while the conflict was in progress. That distinction had to be delayed for a while until the Allies could sort out their zones of occupation, but when the British army did arrive to take over its sector of Berlin, in the vanguard were the armoured scout cars that had done so much to clear the path of the Allied forces.