Modern-day Knights

The armoured warrior on horseback had dominated the battlefields of Europe for a millennium, but the advent of firearms had generally caused the disappearance of armour. By the end of the eighteenth century, most cavalry had abandoned it altogether. However, in the Napoleonic Wars armour made a comeback, especially in the French cavalry. Marshal Ney came up through the ranks as a cavalryman and was particularly fond of heavy cavalry – in spite of his early service with the hussars – and, along with General François-Etienne Kellermann (1770-1835), lobbied Napoleon to create more armoured cuirassier regiments.

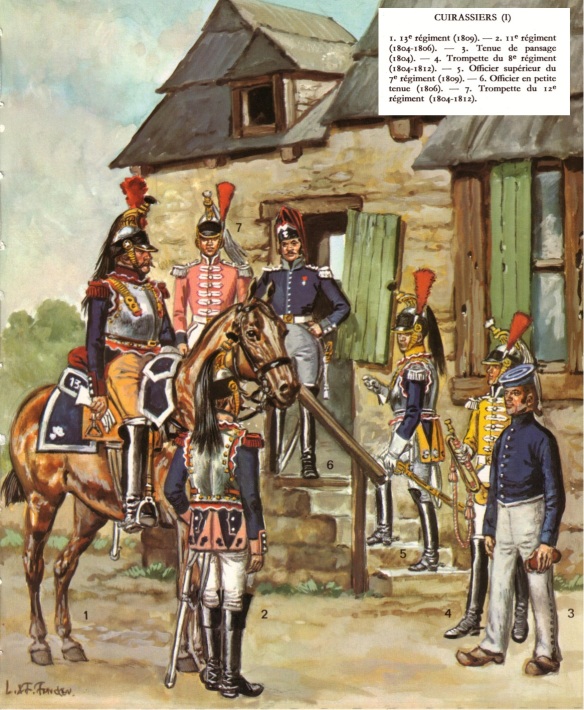

Upon Ney’s recommendation and Napoleon’s own positive experiences with these armoured horsemen, a total of 14 cuirassier regiments were raised. French cuirassiers wore a heavy iron cuirass, which consisted of a breastplate and backplate to encase the horseman’s torso in armour but leave the arms unencumbered and free for action. Armed with a large, straight sabre, heavy cavalry were the modern incarnation of knights – big men on great horses who were used almost exclusively for shock action on the battlefield itself. Besides armour, these horsemen were equipped with a brace of pistols and a carbine, though within a short time most cuirassiers had dispensed with the latter. In 1812 Napoleon ordered French carabiniers to wear the iron cuirass. The carabiniers protested the order, since they believed that it essentially turned them into cuirassiers and thereby diminished their branch of the cavalry. So, to distinguish them from their rivals, decorative copper plating was added to their iron cuirasses, lending carabinier armour a golden appearance.

These ironclad horsemen came to be a dominant force on the battlefields of Europe, and the French cuirassiers and carabiniers became the bane of the Allied armies. Indeed, in the campaigns against Austria, Prussia and Russia during 1805-07 the cuirassiers proved themselves the finest heavy cavalry in Europe. They were an almost irresistible force on the battlefield, and Napoleon increasingly relied upon their dramatic charges to finish off a shaken enemy and win the day. Napoleon lavished rewards upon the cuirassiers. They were authorized to wear the red plume and flaming grenade symbol of elite troops, and as such received extra pay. He kept their scouting and screening duties light, and avoided involving them in skirmishes in order to reserve them for action in major battles.

Although the Austrian, Russian and Prussian armies contained regiments of cuirassiers, they never quite matched the skill and audacity of their French counterparts and were routinely bested on the battlefield. Indeed, many Allied regiments even dispensed with the cuirass, citing issues of weight and problems of manoeuvring in the saddle. By 1809 the Austrians had begun to place a demi-cuirass on their cuirassiers, which covered only the front part of the torso, leaving the flanks and back exposed. While this lightened the cuirassiers’ load and made it easier on their horses on campaign, it also made them more vulnerable in melee combat with French heavy cavalry.

For example, at the battle of Eckmühl in 1809, French cuirassiers dealt a stinging defeat to their Austrian counterparts. During the course of the engagement, the French inflicted nearly five times the number of casualties on their opponents, and much credit for this accomplishment was given to the superior armour of the French horsemen.

Cuirassier Equipment

French horsemen found the extra weight of the full cuirass negligible, and while certainly more encumbered than an unarmoured opponent, they believed the defensive benefits of the armour far outweighed any inconvenience. The cuirass could easily turn aside an enemy blade and could even stop the low-velocity lead balls that were the standard frrearms projectiles of the age. Thus, as these ironclad cavalrymen spurred their horses into a headlong charge, they felt a certain comfort in their perceived invulnerability. Other heavy cavalry, such as dragoons and the famous Grenadier a Cheval of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, lacked body armour. Therefore, it was common practice for dragoons to take their cloaks and roll them into a crossbelt of heavy cloth that they wore diagonally across their torsos. This improvised ‘armour’ actually provided some protection from enemy blades.

Besides body armour, all types of heavy cavalry in every nation’s army wore some kind of helmet. A horseman charged into battle bent forward over his saddle, and thus his head was thrust forward and vulnerable. Some helmets were made of thick leather, such as British dragoon helmets, which were both stylish and functional. Although light, they were capable of deflecting sword blows or lance thrusts and offered a modicum of protection from spent musket balls.

Russian, Austrian and some French dragoons also wore leather helmets, though in widely different styles. French cuirassiers and carabiniers wore iron helmets. Although ornate by modern standards, with their distinctive high brass combs and horsehair plumes, they provided real protection to their wearer from enemy blades and bullets, and were the best helmets worn by any horsemen.

Heavy cavalry attacks were an awe-inspiring sight. Drawn up in great masses of squadrons, these horsemen charged with tremendous fury, forming a mounted fist of steel that could smash through a weak point in the enemy line. They could also be used as an effective counterattack force against an enemy advance. If they could catch infantry in column or line formation and strike their flank or rear, heavy cavalry could wreak havoc, ramming right through such formations and cutting down the foot soldiers or trampling them under the flailing hooves of their powerful steeds.

A heavy cavalry charge would begin with the horsemen advancing at a walk, then increase the tempo to a trot. The idea was to maintain their tight-packed formation as long as possible to maximize striking power when they collided with the enemy. As they closed on their objective, the pace would be stepped up, reaching a thundering gallop in the last 100m (110 yards) until the cavalry crashed headlong into their target, slashing with sabre to right and left as they sliced through the enemy. The sheer mass of these armoured men on their mighty steeds provided a strike force unlike any other on the battlefield.