In December 1805, brigadier general Jean Rapp led a memorable attack at Austerlitz, when he charged at the head of two squadrons each of the Chasseurs a cheval and the Horse Grenadiers of the Guard and the Guard Mameluks and decimated the Chevalier Guards of the Russian Imperial Guard.

Order and Discipline

Like all soldiers, cavalrymen were sometimes guilty of cowardice, malingering and lax discipline. Such problems included heavy cavalry discarding their cumbersome equipment and weapons on long marches in order to lighten their loads. Cavalrymen could also employ tricks to make an animal sick or hobbled – for example, by placing small rocks beneath their saddles in order to make their horses sore-backed. This provided the men with an excuse to take their animals to the rear, thus avoiding action.

At times cavalry were guilty of excesses against civilians. Sometimes lax discipline was viewed as one of the few comforts available while on arduous service, and the light cavalry seemed to take the greatest advantage of the liberty of action bestowed upon them. Light cavalry were not a welcome sight to civilians, be they countrymen, allies or enemies. The light horsemen lived, fought and marauded beyond the bounds of normal society and had a disdain for their own lives, let alone the lives of others. Looting was commonplace, and light cavalry managed always to find time for it, even when engaged in their assigned martial activities. Such activities, which could also include murder and rape, occurred with the compliance, and sometimes even the participation, of their officers. The Cossacks of Russia acquired the worst reputation of any light cavalry during the Napoleonic Wars. These wild nomads were barely controllable within the boundaries of the Russian Empire, never mind when they were set loose upon the peoples of Europe. Even Russian allies such as Austria and Prussia complained vociferously about the conduct of these marauders within their territories, so it is easy to imagine the despicable nature of Cossack activities in the territories of France and its allies.

Organization of cavalry varied greatly from army to army. The Austrians and Prussians, for example, arranged their cavalry in divisions, which were attached to their armies or, after the reforms of 1807-09, to a parent corps. The traditional role of assigning cavalry to the wings of an army/corps to defend its flanks continued in these forces. Although each French corps had a light cavalry division assigned to it, Napoleon also formed separate corps of cavalry and horse artillery. On the day of battle, Napoleon would gather the bulk of his cavalry corps into a formidable Cavalry Reserve, which was held out of battle in the centre of his position. He would allow his infantry and artillery to engage the enemy and develop the attack, and when the enemy had been properly softened up, or an opportunity presented itself, he would unleash his horsemen in a powerful charge against the enemy’s weak spot. Although an artillery officer by training and inclination, Napoleon appreciated the shock power of cavalry in battle. Often it was a charge by the units of this Cavalry Reserve that decided the day; or in some cases saved it, as was the case on the snow-covered fields of Eylau in 1807.

Cavalry Types

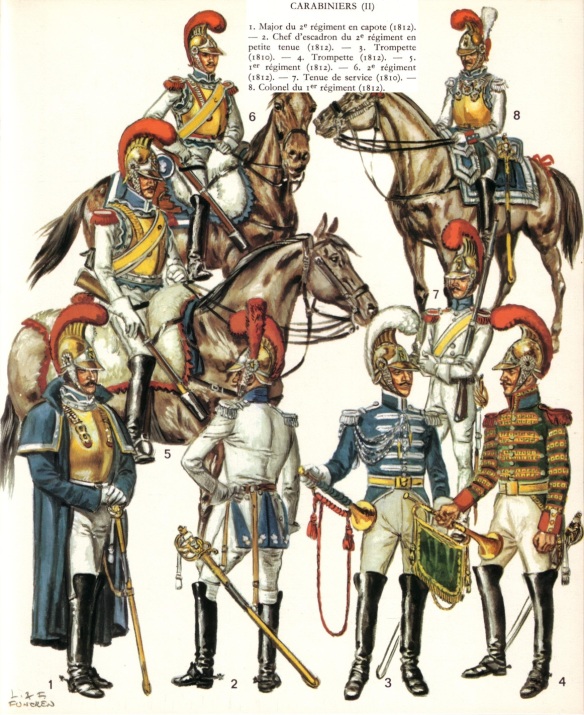

Delivering shock action on the battlefield was but one of many functions the cavalry was called on to perform. In addition, horse troops were used for reconnaissance, screening an army’s movements and for pursuit of a defeated opponent. Such widely disparate missions called for different qualities, and consequently the cavalry of the era was classified as either heavy cavalry, reserved for shock action on the battlefield, or light cavalry, charged with most other missions. Cuirassiers, carabiniers and the Grenadier a Cheval of the Imperial Guard were classified as heavy cavalry. Dragoons and lancers (uhlans in the Austrian and Prussian armies) were really a hybrid between heavy and light and thus were often used for shock action on the battlefield as well as traditional light cavalry missions. The British Army separated their dragoon formations into heavy dragoons and light dragoons (bah!) specifically to differentiate the role of a particular regiment, although even then there was some crossover brought about by the exigencies of a campaign.

Light cavalry received their general classification because they and their mounts were smaller than their counterparts in the heavy cavalry. Hussars were the most numerous of the various types of light cavalry found in the armies of the day. Their traditional braided dolmans, resplendent in a variety of bright colours, made them the gaudiest-dressed soldiers of their armies. French, Austrian and Prussian hussars also traditionally wore a moustache and long, braided side locks on either side of the face; with the Russians, facial hair varied, while British light dragoons (bah!) were clean-shaven.

In an age in which weeks and even months of manoeuvre preceded the decisive battle, these light horsemen swarmed the countryside, probing for enemy weak points, seeking out information on strength and location and doing near continuous battle with enemy light cavalry bent on the same mission. Such a role required horsemen with a high degree of motivation and elan, as well as a natural aggressiveness that would allow them to operate independently of the main army, and often deep inside enemy country. They enjoyed a roguish image and a reputation for galloping headlong into impossible situations. This hell-for-leather attitude was best expressed by one of the most famous hussar commanders of the age, General Antoine Lasalle (1775-1809), who quipped: ‘Any Hussar who is not dead by the time he is thirty is a blackguard.’ Lasalle was killed in action at the battle of Wagram when he was 34 years old.

Aggressive pursuit of a retiring enemy force was the key to turning a tactical victory into a strategic triumph that could win a war. Although heavy cavalry was employed in pursuit operations, it was the light cavalry that excelled in this mission, nipping at the heels of a retiring enemy, picking off stragglers and raiding vulnerable supply wagons and baggage trains, never allowing the enemy to completely disengage and recover its footing. Fighting was usually limited in these affairs, and the emphasis was on speed and initiative, hence the light cavalry were in their element.