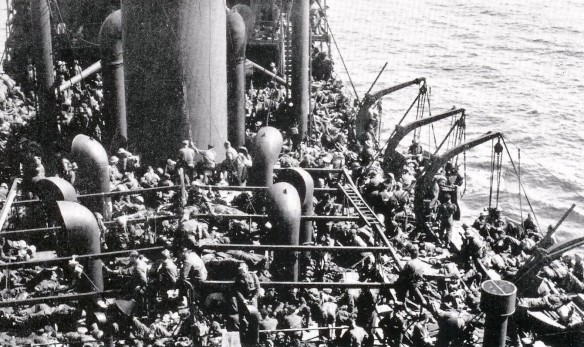

Troop evacuation on SS Guinean during Operation Aerial.

Ports utilised during the evacuation of British and Allied forces, 15–25 June 1940, under the codename Operation Aerial.

During Operation Aerial [or Ariel] , Admiral Dunbar-Nasmith had two tasks at the ports in the southern sector. As well as rescuing a large number of British, Polish and Czechoslovakian troops, he also had the job of trying to stop the French Atlantic fleet from being surrendered to the Germans.

About 85,000 Polish troops had been deployed to France, under the command of General Władysław Sikorski, and were still in the process of being established as fighting formations when the Battle of France erupted. This army was partially destroyed during the hostilities, but over 24,000 men would be evacuated to the United Kingdom where they would form a Polish Free Army.

Similarly, the Czech army in exile in France formed a division consisting of about 5,000 men, commanded by General Rudolf Viest. During the battle this unit was involved in heavy fighting, but most of its personnel were evacuated to reform in Britain as the 1st Czechoslovak Mixed Brigade Group.

In the first instance, it seems that Dunbar-Nasmith was not completely aware of the urgency of the situation and his first action was to send senior naval officers to Brest and Saint-Nazaire on 16 June to begin the process of evacuating stores and equipment. This he thought would take about a week to complete. In Britain the War Office had a clearer picture of what was happening, and he was ordered to begin the evacuation of troops immediately.

The evacuation from Brest occurred between 16 and 17 June, during which a total of 28,145 British and 4,439 Allied personnel were rescued. This included a large number from the RAF, mainly ground crews of the Advanced Air Striking Force. There was very little interference from the Luftwaffe, who carried out no heavy air raids against the port during the extraction process.

Churchill was worried that the French Atlantic Fleet, which was anchored at Brest, would ultimately fall into enemy hands and had ordered Dunbar-Nasmith to do all he could to persuade the French naval commanders to sail to Britain. However, at 16:00 on 17 June most of this armada set sail for French North African ports such as Casablanca and Dakar, with only a small number steering a course for Britain.

The evacuation from Saint-Nazaire did not go as smoothly as at some of the other ports and certainly drew more attention from the Luftwaffe. Saint-Nazaire is situated at the mouth of the River Loire, which is subject to very strong currents so the larger ships had to wait along the shore at Quiberon Bay before moving to the port to pick up evacuees or otherwise have them ferried and boarded offshore. Fifty miles up the river is the port city of Nantes, from where Dunbar-Nasmith was led to believe that somewhere between 40,000 and 60,000 Allied troops were evacuating to Saint-Nazaire, hoping to be evacuated, but he had no idea of when they were expected to arrive.

Lifting this number of men would be a huge undertaking. Dunbar-Nasmith accordingly assembled an impressive rescue force consisting mainly of the destroyers HMS Havelock, HMS Wolverine and HMS Beagle; the passenger liners MV Georgic, SS Duchess of York, RMS Franconia and RMS Lancastria; the Polish ships MS Batory and MS Sobieski; and several commercial cargo ships. Waiting at anchor in Quiberon Bay these ships were very vulnerable to air attack, but British fighter aircraft managed to restrict the Luftwaffe to minelaying. However, this in itself caused delays because special ships fitted out as minesweepers would have to sweep and clear the channels of mines before the evacuation ships could move.

The evacuation started on 16 June when MV Georgic, HMS Duchess of York and the two Polish ships sailed to the port and lifted 16,000 troops before taking them to Plymouth. During the hours of darkness, ships continued to load equipment from the harbour, and two further destroyers, HMS Highlander and HMS Vanoc, arrived to lend a hand.

Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft of No. 73 Squadron flew their last sorties from their base at Nantes before flying off to southern England. Unserviceable Hurricanes were burned by their ground crews, who then made their way towards Saint-Nazaire to be evacuated aboard the ill-fated liner RMS Lancastria.

The Lancastria was built on the River Clyde by William Beardmore and Company for Anchor Line, a subsidiary of Cunard. She was launched in 1920 and was originally called the RMS Tyrrhenia. Designed to carry 2,200 people, including three passenger classes and a crew of 375, she made her maiden voyage from Glasgow to Quebec City in June 1922. In 1924 she was refitted for two classes, renamed Lancastria and sailed scheduled routes between Liverpool and New York until 1932, after which she was employed as a cruise ship. She was requisitioned by the Ministry of War Transport as a troopship in October 1939 and became His Majesty’s Transport (HMT) Lancastria.

On 13 June 1940 she was in Liverpool in readiness for dry-docking and essential repairs, including the removal of 1,400 tons of surplus oil fuel. Her crew had been given shore leave although her chief officer, Harry Grattidge, remained with the ship for the initial stages of dry-docking. Around midday he went to the Cunard office, where he was instructed to recall the crew immediately because the ship had to set sail at midnight. Remarkably, all but three of the crew returned to the ship in time, although naturally the repairs had not been implemented.

The Lancastria first sailed to Plymouth under the command of Captain Rudolph Sharp and from there, accompanied by another of Cunard’s requisitioned ships, the RMS Franconia, set off for Brest with orders to proceed to Quiberon Bay. Approaching their final destination the Franconia was attacked by a single Junkers Ju88 bomber, which caused sufficient damage for her to be returned to Liverpool.

Later that day the Lancastria was ordered to a spot roughly five nautical miles south of Chémoulin Point and nine nautical miles west of Saint-Nazaire, where she arrived early in the morning of 17 June. Here she was loaded with men while at anchorage, with the evacuees being ferried out to her in tugs, tenders and other small craft.

Nobody knows how many people were onboard the ship, but by mid-afternoon on 17 June, estimates vary from around 4,000 to an incredible 9,000; the general consensus is 6,000 plus. Captain Sharp had been instructed by the Admiralty to disregard the limits set down under international law and to load as many men as possible. For a ship that could only comfortably support 2,200, we can only imagine how cramped it must have been, particularly on the upper decks, where men would have occupied every available space.

What is known is that there was a varied group of people on board. As well as RAF personnel there were many of Major-General de Fonblanque’s lines of communication troops and men of the Beauman Division. There were certainly Royal Army Service Corps and Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps troops on board. There were also many civilians, such as embassy staff and employees of Fairey Aviation of Belgium (Avions Fairey), the Belgian-based subsidiary of the British Fairey Aviation company that built aircraft for the Belgian government. Its workers had been evacuated to France in order to relocate to British aircraft factories and had ended up at Saint-Nazaire, from where they were taken out to the Lancastria.

The Lancastria was only one of a number of ships in the area, which soon drew the attention of the Luftwaffe. At around 13:50 aircraft attacked and hit the nearby 20,000-ton Orient liner SS Oronsay. Although a bomb hit her bridge, destroying her compass and all her navigating equipment, she survived the attack and fortunately there were no fatalities.

The Lancastria was by now fully loaded and was given the all-clear to depart, but unfortunately the Royal Navy had no spare destroyers to provide her with an escort. Captain Sharp, concerned about the possibility of being a target for German submarines if she set sail alone, decided to wait for the Oronsay to accompany her along with the first available escort destroyer.

While the ship waited a further air raid began, and consequently, at around 15:48, she received four direct hits from Junkers Ju88s belonging to Kampfgeschwader 30. This caused the ship to list, first to starboard and then to port, before she finally rolled over and sank, all within the space of twenty minutes.

The sea where the ship went down was covered with leaking oil including the 1,400 tons that had not been removed in Liverpool, much of which was now burning on the surface. Many of the survivors drowned or were choked by the smoke. The ship only carried 2,000 lifejackets and it is probable that some of these would not have been accessed in time. German aircraft also flew over the scene repeatedly, strafing the men in the water with machine guns and using tracer bullets to light up more of the oil slick.

The actual air raid finished at approximately 16:30 and a number of both French and British vessels came to pick up survivors. For instance, the trawler HMS Cambridgeshire, which was the first vessel to arrive, took on board around 900, most of which were then transferred to the steam merchant ship John Holt. There were 2,447 survivors in total but the number of those who died is unknown. Over the years The Lancastria Association, established to preserve the memory of those who perished, has researched a list of 1,738 people who were known to have been killed. However the real figure is unquestionably much higher than that: modern estimates range from between 3,000 and 5,800 fatalities, which would represent the biggest loss of life in British maritime history.

The seriously wounded were taken to Saint-Nazaire for medical treatment but most of those whom were rescued were ferried back to Plymouth. The destroyers HMS Beagle and HMS Havelock took 600 and 460 respectively; the John Holt carried 829; the tanker Cymbula another 252; and the liner RMS Oronsay 1,557. Lesser numbers were also evacuated in other ships.

Coming amidst the news of so many unfolding disasters, Winston Churchill initially forbade newspaper editors to publish the story, and consequently the sinking did not become common knowledge in Britain for a number of years. The families of those who were known to have perished were simply told that their loved ones died fighting with the BEF in France. Churchill intended to lift the ban after a few days but the disaster was quickly followed by the French surrender, the fear of invasion and the start of the Battle of Britain. Under the intense pressure of these momentous occasions Churchill forgot to lift the ban until he was reminded of it again later in the war.

Later, on the night of 17 June, HMS Cambridgeshire was ordered to evacuate the commander-in-chief of the BEF, Alan Brooke and his staff. Because the ship had been involved in the rescue of men from the Lancastria, there were no rafts or lifejackets onboard and the decks were strewn with discarded clothing. The ship sailed from Saint-Nazaire at 15:00 on 18 June and arrived in Plymouth late on the afternoon of the following day, having acted as an escort to a convoy of evacuation ships en route.

After the sinking of the Lancastria the evacuation from Saint-Nazaire continued, with a convoy of ten ships lifting 23,000 men just after dawn on 18 June; this left only 4,000 still to be evacuated. However, the next part of the operation became slightly frantic as Dunbar-Nasmith was informed that the Germans were about to storm the port. At 11:00 a.m. that same day, further ships picked up the last 4,000 men but failed to retrieve a large amount of military equipment and supplies in their haste to escape.