The past decade has seen a resuscitation of scholarly interest concerning the military arm of pharaonic Egypt. This reinvigoration of a perennial topic has brought with it a deeper understanding of the cultural aspects of the warrior class as well as a more fundamental perception of the archaeological implication of war logistics. The emphasis upon the Egyptian New Kingdom, nonetheless, remains strong, if only due to the wealth of textual (inscriptional and literary) information still extant and the accompanying artistic depictions. Yet one must turn back to the Second Intermediate Period in order to see the fundamental substructure of the war machine of the Egyptian empire, a foundation that owed its importance to new technology and a new ideological framework (Cavillier 2001).

The period of Hyksos domination in Egypt, traditionally placed at the end of the 13th Dynasty and running through to the reign of Ahmose, first king of the 18th Dynasty, remains a very controversial and complicated subject (Oren 1997; Ryholt 1997: 295-310). Among all of the chronological and historical uncertainties, one of the more difficult remains that of the arrival of the horse and chariot in Egypt. Not surprisingly, the origins of the words for the new modes of warfare, encompassing war material (for example, armour, swords and chariots), are either Semitic or cannot be identified.

Although it took some time for the development of a military caste of elite chariot warriors to rise within the social sphere of the Nile Valley, there is no doubt that a transformation of the state, including its king, was the outcome. In particular, we can note the new ideological flavour of the 18th Dynasty monarchs. Repeatedly, they went to war. Campaigns became part and parcel of their normal activity. When young, princes were fully integrated within the Egyptian army, learning the special crafts of charioteer warfare and being inculcated with the ideology of an expanding Egyptian state. At the same time, these men were closely associated with their non-royal compatriots, officers within the army, whose backgrounds reflected the importance of their families at home.

Because horsemanship and driving war vehicles were now a desideratum for any future pharaoh, so too was the ability to lead men and to organize, both tactically and strategically, the manoeuvres necessary to propagate this new ideal. But there was yet another embedded feature of kingship: pharaohs were now skilled archers. Their `sporting activities’ were no longer limited to hunting or fishing but now included archery, handling of horses and chariots, spear/javelin throwing, oarsmanship and the like. How much the presence of foreign specialists within Egypt aided the Egyptians to advance on their own with these new technologies is another matter. The switch from copper to arsenical bronze was accomplished in the 12th Dynasty but the introduction of `true’ bronze for use in axes, to take a case in point, was later (Davies 1987: 96-101). It is possible that the frequent numbers of Canaanites (or Syrians) who resided in Egypt in the late Middle Kingdom helped to prepare a basis of reception for the acquisition of these new military items (Sparks 2004).

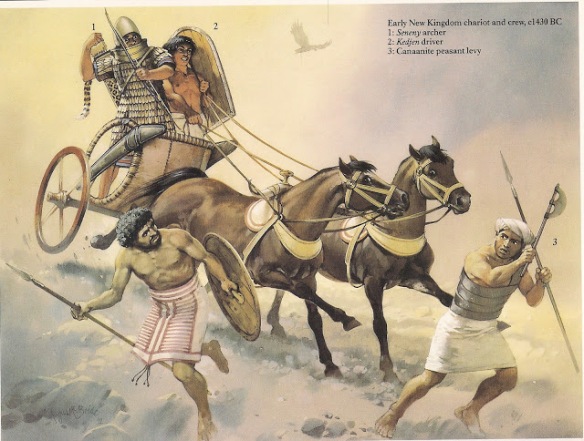

In the time of the Hyksos, one type of small horse was imported into the eastern delta (Decker 1965: 35-59; Spalinger 2005: 8-15). The exact date cannot be deter mined with accuracy, despite the on-going excavation at the Hyksos capital, Avaris (Tell el-Dab’a). Coming from Western Asia, equids had been domesticated for a long time in the steppe regions of southern Russia, and slowly but surely this art moved into the Near East. Along with the horses came chariots, vehicles that at first were small and clumsy, having two wheels that were solid. Later, changes in technology as well as technique meant that by c. 1800 BC lightweight chariots with two wheels (each having four spokes), and drawn by two horses, became the norm (Littauer and Crouwel 1979). With them came a whole group of military men, the charioteers, who were to form the higher level of military society (Gnirs 1996: 17-34).

These changes can be observed by the end of the 17th Dynasty. At that time, the southern state of Thebes, controlling approximately 40 per cent of the length of Egypt, was at war with the north (the Hyksos) and the south (Nubians). The `mutually hostile state’ of Egypt’s relations with the Nubians is nowhere better seen than in the evidence from the tomb of Sobeknakht of Elkab (Davies 2003a). Earlier written evidence allows us to picture an encapsulated Theban state, beset by enemies to the north and the south, but one that was able to press forward owing to its theological political foundations (Vernus 1982; 1989a). Indeed, at this time the native southern Egyptian concept of `victorious Thebes’ became overpowering (Helck 1968: 119-20; Aufrere 2001a). True, the personalized concept of the capital of a native Egyptian state, in this case Thebes of the 17th Dynasty rulers, goes back to earlier divided times, specifically to the First Intermediate Period (Franke 1990; Morenz 2005). But in the Second Intermediate Period there was an added factor, namely the foreign occupation of Egypt. From the south, Nubians penetrated downstream, while in the north a foreign-based dynasty held power over the entire delta as well as central Egypt, ultimately controlling Middle Egypt up to Cusae. The galvanization of any political strength could only come from an amalgam of a new theological-political basis as well as the new military forms of warfare used by the Hyksos themselves.

Because of its relatively limited extent, Thebes at the beginning of the 17th Dynasty was forced to develop a new military arm, based on a large number of its young men who could use horses and chariots, but who also had to be inculcated with a messianic feeling of nationalism (Ryholt 1997: 181-3, 301-10). That there was no simple, single cause-and-effect relationship among all the developments in military technology is clear (Shaw 2001). For example, a large number of military men, the so-called `king’s sons’, proliferate in the epigraphic record at this time (Schmitz 1976; Quirke 2004a). They were personally connected to the pharaoh, not by physical birth but, rather, through social and economic dependence. Equally, the administrative set-up of the Theban state reveals that some key cities and nomes possessed garrisons and military commandants, in addition to the expected civilian mayors. It is clear that this kingdom operated in a high state of military preparedness. Yet it still retained the naval orientation of earlier times. The royal flotilla was the basis of the army, and despite the gradual increase in importance of the chariotry, the old elite of marines formed the backbone of the Theban military (Berlev 1967).

The advantages that the Thebans had over their foes in the north and the south are hard to determine. Over time, they had organized a centralized state which, owing to its geographical limitations, could be easily run on a military basis. Yet practical considerations are never the only factor determining social cohesion and success. As noted above, the kingdom was set within a theological concept that placed the city of Thebes and its god Amun at the core. The Amun theology was linked with the warrior aspect of the monarch and thus his kingdom. `Victorious Thebes’ was not merely an image: it was as much a personification as an extension of the will of pharaoh and of the Theban godhead, Amun (Assmann 1992a). This feeling, one that can be seen later in private inscriptions (such as that of the naval man Ahmose Son of Abana), indicates that Thebes was `our land’. In other words, a strong and cohesive ideological force was engendered that was able to provide this state, earlier beset by foes, with a raison d’etre for military opposition and expansion. We must remember that Thebes could rightfully claim to be Egyptian in leadership and history, and by now Amun had become, theologically, the father of the warrior-king.

This nationalistic aspect of late Second Intermediate Period Egypt is well illustrated in King Kamose’s wars against the Hyksos and also from later accounts that cover this era of foreign occupation (Habachi 1972a; Smith and Smith 1976). Kamose’s royal account, composed on two stelae by his chancellor Nehy, keenly reveals the cultural bias against Apophis, the Pharaoh’s enemy. The Hyksos ruler is always called an `Asiatic’. The dichotomy between him and the son of Amun, `Kamose-the-Brave’, is a theme that runs throughout the inscriptions. Both of them were set up within the religious precinct of Karnak. All that the god wished came to pass, the result being Kamose’s victory celebration upon his return to the capital. The purpose of the narrative account was not to describe the war in a classically narrative manner. Instead, there are various literary strands from different sources that enter into the composition. For example, we learn of a previous conflict between the Thebans and the Nubians. The remarkably swift move north by means of the royal fleet is never explained, and on the basis of a later story, Apophis and Sekenenra, it is assumed that the warfare recounted here is actually a continuance of recent conflict of Thebes versus the north (Wente 1973). But the collective memory of the entire Hyksos episode, in conjunction with the final wars of `expulsion’, was purposely kept in mind by the rulers of Thebes for some time, and indeed propagated to and by the elite (Redford 1970; Assmann 1992b, 1997). It is worthwhile to note that a later ruler of Egypt, Hatshepsut of the mid-18th Dynasty, still felt it effective to refer to Egypt’s `occupation’ by the Hyksos, in order to bolster her propaganda (Allen 2002b).

This persistent attitude of extreme hostility is the major aspect of both Kamose’s official war record and that of the soldier-sailor Ahmose son of Abana (Lichtheim 1976: 12-15). Both place emphasis upon the direct moves against the Hyksos citadel at Avaris. Kamose has his narrative interrupted by a letter from the Hyksos ruler to his Nubian counterpart, promising an alliance, and uses the event to show to the elite of Egypt how dastardly were his opponents’ plans to crush the Thebans from two directions, the south and the north. Ahmose son of Abana, on the other hand, is keen to demonstrate his ability on the field, but likewise places emphasis upon the trapped nature of the foe while proclaiming his role in terms that are overtly nationalistic and xenophobic.

But there is additional information that can be brought into the equation. After Kamose died, he was followed by Ahmose, possibly his younger cousin (Bennett 1995: 42-4). The wars in the delta still continued. We lack any narrative, literary record of war from this time, even though Ahmose published an important document, the Tempest Stela, in which the Hyksos’ control over the land was associated with a recent storm (Wiener and Allen 1998). The manifestation of `the great god’, clearly Amun, is placed at the forefront of the literary account. Ahmose, with his troops on both sides of him (note the military setting of the king) and the council to the rear, inspects his territories and later restores cult centres and ritual activities that had ceased. A new interpretation of the monument has placed emphasis upon possible unrest caused by the ongoing wars in the north with the Hyksos, and there is little doubt, when one examines the chronology, that the final conquest of the Hyksos capital took at least ten to 15 years of warfare. Evidently, the king’s presumed success was won after a long and hard-fought struggle (Spalinger 2005: 22-4, 31 note 36). The so-called Tempest Stela is significant in this context as it appears to indicate that the king’s presence away from his capital, Thebes, at least in his opening years, was considered to be a problem. The account of the `catastrophe’ was theologically interpreted as `a manifestation of Amun’s desire that Ahmose return to Thebes’ (Wiener and Allen 1998: 18). Unfortunately, the extent of the damage to the inscrip tion, as well as the difficulty in separating metaphors from their core literal meanings, hinder our understanding of this important composition.

We are fortunate to possess a series of fragments from Ahmose’s religious complex at Abydos. There, in limestone, was carved a series of narrative scenes in which the king’s final move against the Hyksos fortress at Avaris was depicted. In addition, the presence of the royal fleet reveals the enduring necessity at that time for the use of the marine-based army system for campaigns within the Nile Valley. After all, travel by water was considerably more effective in time and expense than travel by land. Because the Nile served as the umbilical cord for transportation and communication, he who had control of Egypt’s only river possessed the kingdom. Thus the traditional nature of Egyptian warfare had been ship-based, and Ahmose, in his war reliefs, indicates that this system was still in place (Harvey 1998, 2004; Spalinger 2005: 19-23). Elsewhere, the king deports himself in a chariot, shooting his arrow from his massive bow, a scene that was to be the fundamental iconic base of all Egyptian visual narratives of war (Heinz 2001). The helpless opponents flee away from the superhuman king and his army. What distinguishes these pictures from later ones is the presence of Ahmose’s fleet. Because subsequent wars of the New Kingdom were concentrated in lands to the north, south or west, such visual narratives selected the natural means of fighting: with horses and chariots, and accompanying footsoldiers and charioteers. All of the later images of power reverberate through these reliefs. The mimetic restructuring of the king no longer placed him solely, or even mainly, within cultic roles at home, but now located the ruler far away from the capital and engaging a perennial foe. The fact that Ahmose’s enemy was an Asiatic helped him to no small degree in redrawing the cultural boundaries of his nascent dynasty. Most certainly, with the fall of Avaris, the way was open for a consolidation of Egyptian trade routes and mercantile centres on the southern coast of Palestine.