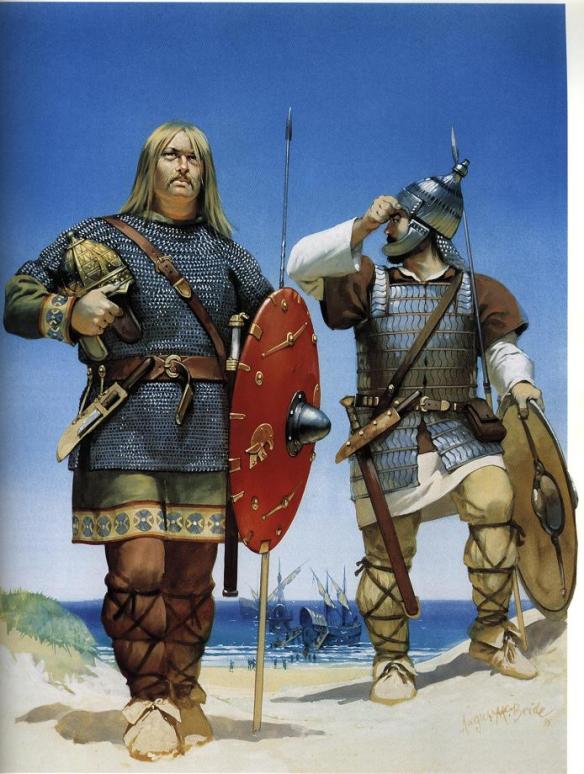

Vandals

Romans

The Gathering Storm

At some point at the end of the fourth century or beginning of the fifth, the Huns moved westward again. They occupied the Hungarian plain and sent a new wave of refugees up against the Roman frontiers. This time the Vandals were amongst them. Led by Godegisel, the Asdings were probably the first to move and some were pushing up against the Danube and raiding into Raetia as early as 401. These early Vandal raiders were defeated by Stilicho and some of the survivors may have been engaged as foederati (federates), given land in exchange for military service.

It is worth pausing for a moment to consider just how momentous a decision it must have been for the Vandals to up-sticks and move. Despite their later wanderings, the Vandals were settled farmers and not nomads. They had lived in more or less the same part of central Europe for hundreds of years and by migrating westward they would leave everything that was familiar behind forever.

The decision would not have been taken lightly, nor quickly. Around the council fires there must have been many voices arguing to stay put and come to some sort of accord with the Huns. Other Germanic peoples, such as the Gepids, did take that option and in the end seem to have done fairly well by it. It may be that the decision to move was influenced by other factors than simply terror at the approach of the Huns. In all likelihood some warriors decided to strike out early, like those who raided Raetia in 401, then as conditions worsened others made the move, taking their families with them.

Procopius, writing in the sixth century, attributes the Vandal migration to famine. Perhaps there had been several poor harvests which made staying put in face of the advancing Huns a less than promising option. It is also interesting to note that Procopius also says that not all the Vandals migrated: `When the Vandals originally pressed by hunger, were about to remove from their ancestral abodes, a certain part of them was left behind who were reluctant to go and not desirous of following Godegisel.’

It is generally assumed that, unlike the Goths, all the Vandals – both Silings and Asdings, men, women and children – migrated west in the early fifth century. Archeology tends to back this up. Material goods connected with the so-called Przeworsk culture have been found in the Vandals’ central European heartland dating back centuries. Then, suddenly, from the start of the fifth century these artefacts disappear from the archeological record entirely. It may be that there was a split as Procopius says and that the end of the Przeworsk culture could be accounted for by the warrior elites moving on, leaving the others behind to fall under Hun overlordship or be absorbed by other tribes. We cannot know for certain but on balance it would seem as though most, if not all, Vandals moved west to seek a new home inside the Roman Empire. This would not have been a coordinated migration but rather decisions made by individual groups, with some moving earlier and others joining in later. As each group made their decision, they would have had to weigh up the difficulties of their present situation against the possibility of a better life in the future.

What realistic hope did the Vandals have of carving out new lands for themselves inside the Empire? Most barbarian incursions into Roman territory were doomed to failure. They might achieve initial success but eventually the Romans would prevail, destroying the invaders and following up with punitive raids against their homelands. The aftermath of Adrianople in 378 had broken this mould. When the Vandals were contemplating their options they would have been well aware that the descendants of the Gothic victors at Adrianople had both land and status within the Empire. The Franks had also been granted land on the west bank of the Rhine in exchange for military service, and all the tribes along the Rhine frontier – Franks, Burgundians and Alamanni – had done quite well out of recent treaties with Stilicho.

The Vandals must have thought that they too could hope for a similar arrangement, especially if the man in charge, Stilicho, was himself a Vandal on his father’s side. Jordanes goes as far as to say that the Vandals were invited into the Empire by Stilicho:

`A long time afterward they [the Vandals] were summoned thence [to Gaul] by Stilicho, Master of the Soldiery, Ex-Consul and Patrician, and took possession of Gaul. Here they plundered their neighbours and had no settled place of abode.’

Could there be any truth to this claim?

Gaul had been a thorn in Stilicho’s side for years. It was the place where rivals could and did rise up to challenge him and the Emperor Honorius, whom he protected. His interest was in maintaining his power base in Italy, keeping an eye on Alaric’s Goths in the Balkans and playing politics with Constantinople. The Gallic Army had been decimated in the civil wars of the late-fourth century, and in 401 Stilicho withdrew more troops from Gaul to support his struggle against Alaric’s Goths who were threatening Italy. While the Rhine defences needed bolstering, the last thing Stilicho wanted was another strong Gallic Army to challenge him. Therefore it is not beyond the realm of possibility that he would have been tempted to have his Vandal cousins move into Gaul as his surrogates. Even if Stilicho had not formally invited the Vandals, maybe there had been communications which some Vandal leaders had interpreted as an invitation, even if they were only meant as polite diplomatic words.

Virtually all modern historians discount collusion between Stilicho and the Vandals, despite the former’s ancestry and despite the fact that he did very little to oppose their crossing into Gaul. The Vandals were not the only barbarians on the move. Goths, Suevi, Alans and others were forced out of their central European homelands by the Huns, famine or both in the first years of the fifth century. Even when the Vandals crossed the Rhine, they were probably a minority partner to the Suevi and Alans. Furthermore, Stilicho’s policy had been to rely on the Franks and other western Germanic tribes to secure the Rhine for him in place of Roman soldiers. This policy seemed to have worked relatively well and there would have been no reason for him to change it. In the unlikely event that there had been any understanding between Stilicho and some of the Vandal leaders, the chain of events in the first decade of the fifth century were so cataclysmic to overwhelm all involved.

All of a sudden hundreds of thousands of people were willingly or unwillingly on the move, and the Vandals were only a small part of this movement. Most probably the decisions to migrate were sparked off by the westward expansion of the Huns, but no doubt many other factors came into play as well. These may have included food shortages, although the climatic records from around 400 do not reveal any unusual weather patterns. Probably there was also a degree of opportunism on the part of the Vandals, Suevi and Alans, as they saw how Stilicho was otherwise occupied and knew that the Rhine defences were relatively thin.

As the Huns migrated from the Eurasian steppes into central Europe, the first wave of displaced Germans to break over the Roman frontier was led by Radagasius, a Goth, who brought a large army into Italy in 405. The composition of Radagasius’ force is not known but probably it was a coalition of various Germanic peoples, possibly including some Asding Vandals. It included women and children as well as warriors, so it was a migration rather than a raiding force. Radagasius’ force was large enough to require Stilicho to call on thirty units from the Roman field army as well as Hun and Alan auxiliaries to oppose him. He also withdrew yet more troops from the Rhine frontier to bolster Italy’s defences. This probably gave Stilicho something in the region of 20-25,000 men.

It is interesting to note that, according to the Notitia Dignitatum, the Italian field army contained seven cavalry and thirty-seven infantry units in the fifth century, with another twelve cavalry and forty-eight infantry units in the Gallic Army. These were on top of the border troops stationed along the frontiers. Yet it took a great deal of time and effort to gather the thirty units needed to oppose Radagasius, leaving the invaders plenty of time to ravage northern Italy while Stilicho marshalled his forces. This is good example of just how misleading official army organizational lists can be. Unit strengths and levels of readiness can vary hugely and often only a tiny fraction of the theoretical military capability can be deployed. This remains a problem even in the modern world. If we think of the huge efforts it took by NATO nations and others to maintain relatively small numbers of troops in Afghanistan to deal with insurgents, then we have some idea of the problems facing the Romans in the fifth century.

In the end, Stilicho decisively defeated Radagaisus near Florence on 23 August 406. Then he fixed his attention firmly on the east, oblivious or unaware of the storm gathering to the north and west.

The Storm Breaks

The coalition of Asding and Siling Vandals, together with Alans and Suevi, crossed the Rhine on 31 December 406. This is the date given by Prosper of Aquitaine. In recent years some historians have made a case for the crossing taking place a year earlier – that is on 31 December 405. This is partly based on the fact that Zosimus says that the ravaging of Gaul took place in 406 and it is unlikely he would have assigned that year if the barbarians only crossed on the last day of it. Also in 406 there were a number of usurpations in Britain and these are often seen as a reaction to the lack of response to the invasion of Gaul by the Imperial authorities. To make matters more confusing, Orosius says that the Rhine crossing took place two years before the Gothic sack of Rome, which would be 408.

The arguments is for shifting the occasion of the Rhine crossing and therefore we prefer to stick with the rather precise date Prosper has given us of New Year’s Eve 406. But before trying to reconstruct the actual Rhine crossing itself, we should look at what was happening in the months that led up to it.

By the end of 405, Stilicho had defeated Radagasius and incorporated 12,000 of the survivors into his army, while others dispersed to join Alaric’s Goths in the Balkans and the westward-moving Vandals. In 406, a series of revolts took place in Britain with the British Army proclaiming Marcus and Gratian in quick succession as Emperor before assassinating their candidates when they did not do as the army wished. Towards the end of 406, the British Army settled on a soldier with the suitably Imperial name of Constantine (Constantine III), who managed to retain their approval. Meanwhile Stilicho became embroiled in a fight with Constantinople over control of the Balkans. Parts of the Balkan provinces had previously belonged to the Western Empire but had been transferred to the East several years earlier. Stilicho wanted them back as they were a prime recruiting ground for soldiers. Additionally, it would give him territory he could offer to Alaric in order to finally come to a lasting and peaceful settlement with his troublesome Goths.

Meanwhile, the Vandals had been moving slowly westward as part of a greater movement of displaced peoples. After the failure of Radagasius’ migration across the Danube, the southern route into the Roman Empire had to be ruled out, leaving the Rhine frontier as their only hope. If we discount any collusion with Stilicho, it is unlikely that the Vandals had detailed intelligence of the state of Roman defences along the west bank of the Rhine, just as Stilicho was apparently unaware of the large westward movements beyond the frontier. This does, of course, call into question whether or not there may have been some collusion.

The problem for the Vandals was that if the west bank of the Rhine may have been relatively weakly defended, the east bank was not. The powerful Alemannic and Frankish confederacies were well established on the upper and lower Rhine respectively, with the Burgundians edging into the gap between them. These tribes had been in long contact with Rome and had benefited from it. Their societies had greater material wealth than the Vandals, more developed organizational structures and they were being subsidized by Rome to hold the Rhine frontier. The last thing they would have welcomed would have been a new group of illegal immigrants knocking on their door for a piece of the action.