Bristol Blenheim Malta

On 24 June, led by Wing Commander Atkinson, crews on 82 Squadron delivered the first low-level attack on Tripoli harbour, where they bombed the remainder of the convoy that they had attacked two days earlier. That day, it was said, the Squadron really went to town -Tripoli town – at anything from twenty to nought feet. The Wing Commander and two others bombed a 20,000-ton liner and his gunner saw the whole of the top deck blow off.

The squadron continued to operate daily from Luqa, suffering heavy casualties until they could operate no longer. One of their operations worth recalling, was another low-level raid, led once again by Atkinson, on the harbour at Palermo on the north coast of Sicily, which they approached by flying through the Sicilian Channel and coming in from the north. Having dropped their bombs they headed due south across this mountainous island and back to Luqa. The enemy was so surprised that not one shot was fired at the Blenheims, yet the raid was an enormous success. Two ships, one a 10,000 tonner, the other of 5,000 tons had been destroyed; another 10,000 tonner had a broken back, whilst three others had been badly damaged.

Their contribution to the Maltese Campaign completed, the surviving aircrew, despite instructions to the contrary, found their way back to the UK to join their beloved 2 Group by hitching a lift to Gibraltar in a Catalina flying boat and then on by ship.

On 1 July 1941 the second detachment, 17 Blenheims and their crews on 110 Squadron, commanded by Wing Commander Theo ‘Joe’ Hunt DFC, flew out to Malta, where they wasted no time in getting into action. Their first operation was a low-level attack on three merchantmen in Tripoli harbour, followed on the 13th with the destruction of three more vessels. The next day they switched their attention to Libya, where they bombed a Luftwaffe airfield with some success, followed four days later by a raid on a power station at Tripoli, where Wing Commander ‘Joe’ Hunt and his crew were shot down into the sea by a CR 42 fighter. Shipping was not neglected, an 8,000 ton merchantman being damaged on the 15th, two ships being destroyed on the 22nd and then four crews bombed and destroyed two more in another visit to Tripoli harbour. In the latter operation the formation leader, Sergeant N. A. C. Cathles, twice hit the sea en-route to the target, which he bombed before he was forced to make a belly-landing in enemy territory. Yet another demonstration of the courage and determination of these young aircrew.

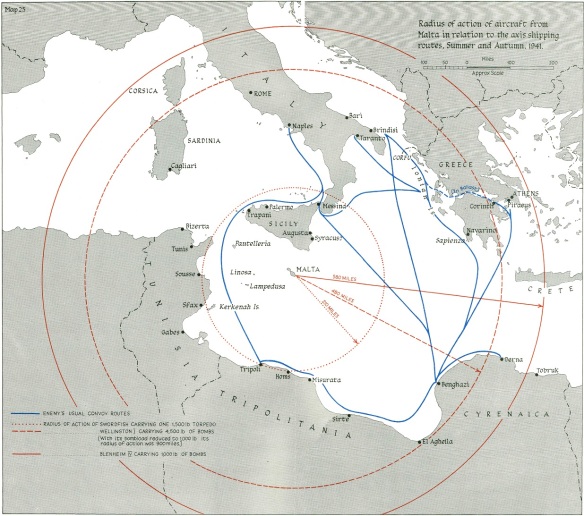

On 28 July, after a short but highly successful attachment, the surviving crews found their way back to the UK, to be replaced by twelve crews on 105 Squadron led by Wing Commander Hughie Edwards VC DFC a matter of a mere 24 days after he had led the epic low-level raid on Bremen. In their first operation six of the crews found a convoy of four merchantmen escorted by a destroyer and Fiat CR 42 fighters, who put up such an effective defence the raid had to be abandoned. The next day three crews found a destroyer escorted convoy close to the island of Lampedusa, which they attacked and lost one of their number to anti-aircraft fire. Apart from flying shipping sweeps the crews were not neglecting land targets such as a barracks at Misura in Libya. In their attacks on shipping they continued to have their successes, as on 7 August, when only two out of a convoy of six ships reached their destination in Africa. One of these, a tanker beached on Lampedusa, where after a second raid, it burnt for days. On the 15th, five crews of 105 Squadron found two escorted tankers, carrying fuel for the Afrika Corps, between Tripoli and Benghazi, which they bombed. One of the tankers exploded whilst the other was very badly damaged, although the Blenheim crews had to pay a high price. The Blenheim piloted by Pilot Officer P. H. Standfast being hit by flak exploded, a second was shot down by machine-gun fire and a third was lost when it collided with the mast of one of the ships and cart wheeled into the sea.105 Squadron were certainly making its presence felt, scoring three hits on two merchantmen on the 28th off the coast of Greece, a shipping sweep so far from Malta it was almost at the limit of their fuel capacity. Then closer to home, they bombed an ammunition factory and a power station at Licata on the south coast of Sicily. On 31 July the command of the squadron had been handed over from Wing Commander Edwards to Wing Commander P. H. A. Simmons, the former returning to the UK for a well deserved ‘rest’.

By the end of August it was estimated that 58% of all enemy supplies heading for North Africa had been lost at sea. Those who successfully completed the journey were still not safe in Tripoli harbour, where they were liable to be bombed by day by the Blenheims and at night by the Wellington crews. Understandably, the enemy did not stand idle in the face of this threat to their lifeline to their armed forces in Africa, increasing the anti-aircraft defences on their merchantmen and escorts. The casualty rate for the Blenheim crews was around 12%, an average of one crew per day or one squadron per week. Replacement crews were found by ‘press-ganging’ unsuspecting crews and their aircraft on their way out to Egypt into service with the squadrons on Malta.

The need to maintain the momentum of attacks on enemy shipping meant that 105 Squadron had to remain in Malta longer than the intended 5-6 weeks. At the end of August 26 Blenheims and their crews of 107 Squadron arrived in Malta to play their part in the campaign. On 17 September three crews flew a low level raid on factories at Licata, whilst at dawn the same day another three crews bombed a large liner in Tripoli harbour and so it continued. On the 22nd in a raid by crews from both squadrons on barracks, ammunition dumps and lorries on the Tripoli-Benghazi road two of the Blenheims collided. The tail was knocked off the aircraft piloted by Wing Commander Don Scivier AFC, which crashed, whereas the other one, piloted by Sergeant Tommy Williams managed to limp back to Luqa. Many convoys were escorted by fighters which, bearing in mind the improved anti-aircraft defences, added to the danger as for example, a formation of six Blenheims found five merchantmen escorted, not only by five destroyers but four Junkers 88 twin-engined fighter-bombers as well. Undaunted the first vie flew into the attack dropping their bombs, followed closely by the second vic led by Wing Commander N. E. W. Pepper DFC. As the latter flew over the convoy the eleven second delay bombs of the first wave exploded, blowing-up Pepper’s aircraft. Another, severely damaged did however manage to limp back to Luqa. An indication of the success of the campaign was that the enemy now stopped routing their convoys to the west of Sicily, sending them on the longer journey via the coast of Greece.

On Thursday 4 October 1941 eight crews on 107 Squadron led by Squadron Leader Barnes, set out to bomb the harbour at Zuara on the African coast. The flak from three destroyers in the harbour was so fierce the first vie was beaten off and they came under attack from Fiat CR.42 fighters. The other five Blenheims sought other targets inland, when they too were attacked by fighters, who shot down the Blenheim piloted by Sergeant D. E. Hamlyn. All three crew spent six days in their dinghy before being rescued off the coast of Djerba by an Arab ship, which took them to Tunis and internment. The engagement with the fighters lasted until the Blenheims were fifty miles out to sea on their way back to base. During the night of 7/8 October, a low-level attack in bright moonlight was carried out on a 2,000 ton merchantman off Tripoli, on which two hits were scored causing an explosion.’

On the 11th 107 Squadron found a convoy in the Gulf of Sirte escorted by one twin-engined monoplane. Flying Officer Ronald Arthur Greenhill hit a large motor vessel forward and his aircraft was then seen by Sergeant Harrison to be hit in the belly and crash in the sea as he climbed over the ship. Sergeant Ivor Broom attacked the same vessel and hit it aft and left the vessel in flames with grey smoke pouring from it. He was chased by the escort plane which did not get within firing range. Harrison saw Sergeant Routh attack a small cargo boat, set it on fire and then crash into the sea having been hit by guns from the large motor vessel. Sergeants Leven, Baker and Hopkinson did not make an attack and brought back their bombs. In the afternoon of 11 October a convoy consisting of the steamer Priaruggia, the tanker Fassio, escorted by the corvette Partenope, which left Tripoli at 1600 hours on 10 October, was attacked by three Blenheims in low-level flight. While turning and climbing the Blenheims dropped a series of small bombs and strafed the convoy with machine guns. Of the bombs, one hit Priaruggia at the base of the funnel. Almost at the same time, two Blenheims appeared to be hit by the precise fire of Partenope, one in a staggering turn trying to touch down on the water, hitting hard and then dived into the sea breaking up. The other, on fire, still managed a half turn and then dived into the sea nose first, vanishing completely. The third Blenheim carried out a wide turn and then continued to remain cruising for some minutes. One of the Blenheims, which prior to crashing, hit the foremast of the Priaruggia, bursting into flames and breaking off the mast. The Priaruggia must have appeared very badly hit, but the Fassio was neither hit nor attacked. The episode shows very clearly the dangers the pilots on Malta exposed themselves to and the brutal and very quick end that awaited most of them. Fassio arrived in Benghasi on 13 October. The lost Blenheims were Z7618 and Z9663. While Sergeant Whidden survived the crash, he died of his wounds in hospital shortly after. Their loss was not completely in vain however. Priaruggia was badly enough damaged that she had to return in tow to Tripoli after an initial stay at Misurata. When she arrived (still with the same cargo, including ammunition) in Benghazi six weeks later, after the conclusion of repairs, she was bombed on the night of her arrival and all her cargo was lost when she blew up.

‘Mid-October saw the arrival of a detachment on 18 Squadron, who were to remain on Malta until the end of the campaign, replacing the surviving personnel on 105 Squadron, who arrived back in the UK on 11 October. The casualty rate was rising at an alarming rate, for instance, the new commander of 107 Squadron was lost on 9 October, followed a few days later by his deputy, Squadron Leader Barnes. By the end of the month the squadron had no commissioned officer pilots left, command falling on the shoulders of Sergeant Ivor Broom, who was awarded an immediate commission. Ivor and his crew of Sergeant ‘Bill’ North, observer and Sergeant Les Harrison, WOp/AG had been on their way to North Africa when they had been hi-jacked by Hugh Pughe-Lloyd.3 During the remainder of October, raids were concentrated on Axis targets in North Africa, although Sicily was not forgotten. On the 17th six Blenheims of 18 Squadron with an escort of Hurricanes carried out a successful ‘Circus’ attack on the enemy’s seaplane base at Syracuse, with other low-level operations being directed against factories at Licata and Catania.

The first major success in November occurred on the 5th, when six crews of 18 Squadron found and attacked two 3,000 ton tankers escorted by a destroyer. They had to pay a high price for their success, as two of the Blenheims were shot down. On the 8th six crews from 107 Squadron found a merchantman escorted by a destroyer, a desperate battle ensued with one Blenheim, on being hit by flak crashed into the ship’s mast and exploded. Another was hit in the turret, yet despite this, the survivors made a further four attacks without gaining any hits on their target. A follow-up attack was carried out by six crews of ..8 Squadron, who lost two of their number without being able to sink the merchantman. Successful attacks during the same period were carried out in low-level

On Thursday 4 October 1941 eight crews on 107 Squadron led by Squadron Leader Barnes, set out to bomb the harbour at Zuara on the African coast. The flak from three destroyers in the harbour was so fierce the first vie was beaten off and they came under attack from Fiat CR.42 fighters. The other five Blenheims sought other targets inland, when they too were attacked by fighters, who shot down the Blenheim piloted by Sergeant D. E. Hamlyn. All three crew spent six days in their dinghy before being rescued off the coast of Djerba by an Arab ship, which took them to Tunis and internment. The engagement with the fighters lasted until the Blenheims were fifty miles out to sea on their way back to base. During the night of 7/8 October, a low-level attack in bright moonlight was carried out on a 2,000 ton merchantman off Tripoli, on which two hits were scored causing an explosion.’