Roman Merchant Ships

The grain trade was not simply a source of profit for Rome’s merchants. In 5 BC Augustus Caesar distributed grain to 320,000 male citizens; he proudly recorded this fact in a great public inscription commemorating his victories and achievements, for holding the favour of the Romans was as important as winning victories at sea and on land. The era of ‘bread and circuses’ was beginning, and cultivating the Roman People was an art many emperors well understood (baked bread was not in fact distributed until the third century AD, when Emperor Aurelian substituted bread for grain). By the end of the first century BC Rome controlled several of the most important sources of grain in the Mediterranean, those in Sicily, Sardinia and Africa that Pompey had been so careful to protect. One result may have been a decline in cultivation of grain in central Italy: in the late second century BC, the Roman tribune Tiberius Gracchus already complained that Etruria was now given over to great estates where landlords profited from their flocks, rather than from the soil. Rome no longer had to depend on the vagaries of the Italian climate for its food supply, but it was not easy to control Sicily and Sardinia from afar, as the conflict with the rebel commander Sextus Pompeius proved. More and more elaborate systems of exchange developed to make sure that grain and other goods flowed towards Rome. As Augustus transformed the city, and as great palaces rose on the Palatine hill, demand for luxury items – silks, perfumes, ivory from the Indian Ocean, fine Greek sculptures, glassware, chased metalwork from the eastern Mediterranean – burgeoned. Earlier, in 129 BC, Ptolemy VIII, king of Egypt, received a Roman delegation led by Scipio, conqueror of Carthage, and caused deep shock when he entertained his guests to lavish feasts dressed in a transparent tunic made of silk (probably from China), through which the Romans could see not just his portly frame but his genitals. But Scipio’s austerity was already unfashionable among the Roman nobility. Even the equally austere Cato the Elder (d. 149 BC) used to buy 2 per cent shares in shipping ventures, spreading his investments across a number of voyages, and he sent a favoured freedman, Quintio, on these voyages as his agent.

The period from the establishment of Delos as a free port (168–167 BC) to the second century AD saw a boom in maritime traffic. As has been seen, the problem of piracy diminished very significantly after 69 BC: journeys became safer. Interestingly, most of the largest ships (250 tons upwards) date from the second and first centuries BC, while the majority of vessels in all periods displaced less than 75 tons. Larger ships, carrying armed guards, were better able to defend themselves against pirates, even if they lacked the speed of the smaller vessels. As piracy declined, smaller ships became more popular. These small ships would have been able to carry about 1,500 amphorae at most, while the larger ships could carry 6,000 or more, and were not seriously rivalled in size until the late Middle Ages.32 The sheer uniformity of cargoes conveys a sense of the regular rhythms of trade: about half the ships carried a single type of cargo, whether wine, oil or grain. Bulk goods were moving in ever larger quantities across the Mediterranean. Coastal areas with access to ports could specialize in particular products for which their soil was well suited, leaving the regular supply of essential foodstuffs to visiting merchants. Their safety was guaranteed by the pax romana, the Roman peace that followed the suppression of piracy and the extension of Roman rule across the Mediterranean.

The little port of Cosa on a promontory off the Etruscan coastline provides impressive evidence for the movement of goods around the Mediterranean at this time. Its workshops turned out thousands of amphorae at the instigation of a noble family of the early imperial age, the Sestii, who made their town into a successful industrial centre. Amphorae from Cosa have been found in a wreck at Grand-Congloué near Marseilles: most of the 1,200 jars were stamped with the letters SES, the family’s mark. Another wreck lying underneath this one dates from 190–180 BC, and contained amphorae from Rhodes and elsewhere in the Aegean, as well as huge amounts of south Italian tableware on its way to southern Gaul or Spain. Items such as these could penetrate inland for great distances, though bulk foodstuffs tended to be consumed on or near the coasts, because of the difficulty and expense of transporting them inland, except by river. Water transport was immeasurably cheaper than land transport, a problem that, as will be seen, faced even a city such a short way from the sea as Rome.

Grain was the staple foodstuff, particularly the triticum durum, hard wheat, of Sicily, Sardinia, Africa and Egypt (hard wheats are drier than soft, so they keep better), though real connoisseurs preferred siligo, a soft wheat made from naked spelt. A bread-based diet only filled stomachs, and a companaticum (‘something-with-bread’) of cheese, fish or vegetables broadened the diet. Vegetables, unless pickled, did not travel well, but cheese, oil and wine found markets across the Mediterranean, while the transport by sea of salted meat was largely reserved for the Roman army. Increasingly popular was garum, the stinking sauce made of fish innards, which was poured into amphorae and traded across the Mediterranean. Excavations in Barcelona, close to the cathedral, have revealed a sizeable garum factory amid the buildings of a medium-sized imperial town. It took about ten days with a following wind to reach Alexandria from Rome, a distance of 1,000 miles; in unpleasant weather, the return journey could take six times as long, though shippers would hope for about three weeks. Navigation was strongly discouraged from mid-November to early March, and regarded as quite dangerous from mid-September to early November and from March to the end of May. This ‘close season’ was observed in some degree right through the Middle Ages as well.

A vivid account of a winter voyage that went wrong is provided by Paul of Tarsus in the Acts of the Apostles. Paul, a prisoner of the Romans, was placed on board an Alexandrian grain ship setting out for Italy from Myra, on the south coast of Anatolia; but it was very late in the sailing season, the ship was delayed by the winds, and by the time they were off Crete the seas had become dangerous. Rather than wintering in Crete, the captain was foolhardy enough to venture out into the stormy seas, on which his vessel was tossed for a miserable fortnight. The crew ‘lightened the ship and cast out the wheat into the sea’. The sailors managed to steer towards the island of Malta, beaching the ship, which, nevertheless, broke up. Paul says that the travellers were treated well by the ‘barbarians’ who inhabited the island; no one died, but Paul and everyone else became stuck on Malta for three months. Maltese tradition assumes that Paul used this time to convert the islanders, but Paul wrote of the Maltese as if they were credulous and primitive – he cured the governor’s sick father and was taken for a god by the natives. Once conditions at sea had improved, another ship from Alexandria that was wintering there took everyone off; he was then able to reach Syracuse, Reggio on the southern tip of Italy and, a day out from Reggio, the port of Puteoli in the Bay of Naples, to which the first grain ship had probably been bound all along; from there he headed towards Rome (and, according to Christian tradition, his eventual beheading).

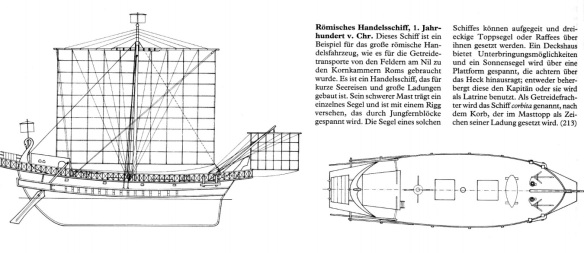

Surprisingly, the Roman government did not create a state merchant fleet similar to the fleets of the medieval Venetian republic; most of the merchants who carried grain to Rome were private traders, even when they carried grain from the emperor’s own estates in Egypt and elsewhere. Around 200 AD, grain ships had an average displacement of 340 to 400 tons, enabling them to carry 50,000 modii or measures of grain (1 ton equals about 150 modii); a few ships reached 1,000 tons but there were also, as has been seen, innumerable smaller vessels plying the waters. Rome probably required about 40 million measures each year, so that 800 shiploads of average size needed to reach Rome between spring and autumn. In the first century AD, Josephus asserted that Africa provided enough grain for eight months of the year, and Egypt enough for four months. All this was more than enough to cover the 12,000,000 measures required for the free distribution of grain to 200,000 male citizens. Central North Africa had been supplying Rome ever since the end of the Second Punic War, and the short, quick journey to Italy was intrinsically safer than the long haul from Alexandria.