Wu Peifu mediate a peace with Zhang Zuolin.

CHIHLI CLIQUE ARMY, 1920-25

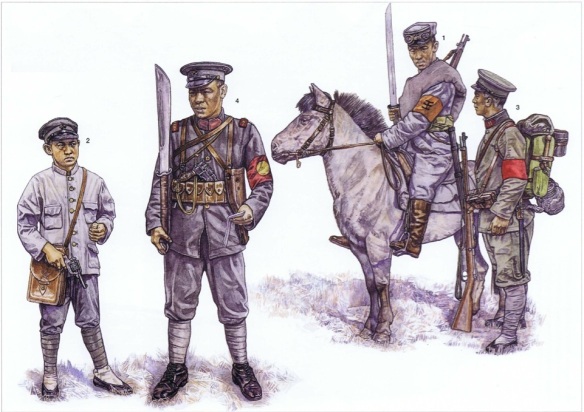

C1: Trooper, 2nd Cavalry, 8th Division, 1923

This cavalryman mounted on a Mongolian pony has a padded cotton jacket and trousers worn with a pair of fur-lined boots, and his peaked cap has sewn-in ear flaps. He has been lucky to receive a pair of motoring goggles, as used by several warlord armies to protect the eyes from dust on the march. The orange armband has the Chinese character for his commander’s surname, ‘Wang’, stencilled In black. In the service of the ‘Jade Marshal’, Wu Pel-fu, General Wang Ju-ch’un commanded the 9,000-strong 8th Division in Hupeh province in 1923. The trooper is armed with a 6.5mm Mannlicher Carcano 91TS carbine, probably imported by Wu Pei-fu as part of a $5.6 million supply shipment negotiated with an Italian arms dealer in 1922. He also has a sword, based on the rna-tao sabre of medieval China; these were used at various times during the early 20th century, and special units of Nationalist troops armed with them fought the Japanese in Jehol province as late as 1933. Some cavalry also used the da-dao fighting sword, but this longer-bladed weapon was more suitable for slashing at the enemy from horseback.

C2: Military courier, 3rd Division, 1924

This boy, aged about 12, is one of those taken out of the officer training school set up by the Chihli Clique leader Wu Pei-fu to help with his army’s communications. During the 1924 campaign Wu was desperately short of reliable troops, and took the officer cadets from their academy to release other men for the front line. Although Wu had a reputation as a relatively humane commander this sacrifice of his army’s future officers would not have worried him unduly; he was reported at the time to have 30,000 boy soldiers in his army, who were all orphans of soldiers killed in previous battles. The boy is wearing the same grey cotton uniform as his adult comrades and has a leather despatch case to carry his messages. For self-protection he has been given an Italian 10.35mm Glisenti M1889 revolver.

C3: Infantryman, 11th Division, 1922

This soldier is about to leave for the front during the fighting against the Fengtien Army of Chang Tso-Iin in 1922; at this stage his grey cotton uniform is still in good condition, but it will soon show wear-and-tear. His infantry-red collar patches indicate, in Roman numerals on his left, his division; his right patch would show his personal details in Chinese characters, such as his number within his unit. This complicated system of identification was occasionally seen, but the exact protocol varied from region to region. His rank of private first class is shown by the stars on the shoulders of his tunic, but again, shortages meant that many soldiers lacked rank insignia. The red armband was described by Edna Lee Booker, a correspondent who saw Wu Pei-fu’s troops leaving for the war. The infantryman is well equipped, with a Japanese backpack and other accoutrements including ammunition pouches designed to carry clips for the Japanese Arisaka rifle, although this soldier is in fact armed with the common Mauser M1888 or a local copy. Booker also described the paraphernalia carried by the troops fastened to their packs; in this case the soldier has a teapot, but others are described as carrying trench picks, shovels, oiled-paper umbrellas, hot water bottles, lanterns and alarm clocks.

C4: Sergeant, ‘Big Sword Corps’, 1924

This NCO belongs to an elite unit of Wu Pei-fu’s army. The ‘Big Sword Corps’ acted as a bodyguard for their commander and were responsible for keeping order, when necessary beheading officers and men who had failed in their duties. (During the fighting against Chiang Kai-shek’s NRA in 1927, Wu had to send this elite corps into battle to try to stem their advance.) As with most soldiers responsible for discipline in Chinese armies, the men of this unit were picked for their stature and strength – the big executioner’s sword needed a pretty strong man to wield it efficiently. The rank of chung-shih is indicated by the stripe and two stars on the shoulder straps, and he has collar patches in the pink of the military police. The red armband with a central yellow disc is one of several types recorded as being worn by warlord troops at the time. Besides the sword – which was not really intended for combat use – he is armed with a Mauser M1896 automatic pistol with a wooden holster-stock, and he has spare clips in the leather pouches at his waist.

After the death of Yuan Shikai in 1916 unified military rule from Peking gave way to disseminated military rule. Within a few months the country was divided into a great number of what were known then as satraps, none of them stable or lasting, all based on regional ties, all dominated by warlords. China had become, as Sun Yat-sen had predicted it would, a sheet of shifting sand. Though there continued to be national governments in Peking they wielded very little power, and came and went with bewildering frequency.

China is a vast and diverse country. The regional diversity is expressed in dialects, often mutually unintelligible, in cuisine, in traditions and customs – and in identity. Before there was an empire there were many independent states, whose names survive in the alternative names of provinces (QiLu/Shandong, ShuBa/Sichuan, Yue/Guangdong).

In the many periods of disunity since the founding of the first state in the third century BC, regional power holding always emerged to fill the void left by a collapse at the center. The process of devolution and fragmentation was one that China knew well. The most famous period of disunity came after the end of the Han dynasty, when China was divided into three. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi), an immensely popular novel written more than 1,000 years after the events it described (and almost certainly apocryphal), told of the anguish of division and civil war through a string of stories of courage, treachery, and intrigue. The stories were known to every Chinese, whether educated or not; they appeared as opera plots, as oral stories, and in cartoons. Disunity was as inevitable as unity, said the Three Kingdoms stories. Some people behaved badly in times of troubles, others came into their own – but the evil men often won; the most evil of all, Cao Cao, triumphed over the greatest strategist, Zhuge Liang, a man of brilliance and humanity.

It may seem a stretch to use a novel as a guide to understanding reactions to disunity and uncertainty – but the mentality portrayed in The Romance of the Three Kingdoms had a formative influence on young men of the early Republic, men such as Mao Zedong, who had all read the novel as boys. Theirs was a Three Kingdoms reaction to disunity: think things through carefully, devise stratagems, and know that the solutions will require force as well as intelligence. The answer was to combine Zhuge Liang’s brilliance with Cao Cao’s ruthlessness.

Warlords and their armies

The rise of regionalism and regional identities had been encouraged by the disappearance of universal examinations in 1905, and by the loss of the law of avoidance. After 1916 the center’s ability to make appointments at the provincial level disappeared, and regional rulers came to power, often soldiers, who called themselves military administrators (dujun); other people called them warlords.

These men saw disunity as opportunity for their particular regions. The negative reactions to warlordism in the civilian world reflected the fear of chaos, of the country falling apart – the fear that had haunted China’s rulers since the beginning of the empire. This fear lived in the metropolitan world of the emperors and the bureaucrats. It was not shared by warlords, men who focused on one region only, nor by many of the people whose lives they controlled, whose horizons did not extend beyond a region and its culture.

In the civilian elite’s stereotype, a warlord was a deceitful, devious, illiterate man, sunk in backward patterns of behaviour, uncouth and filthy. Zhang Zongchang, the “Dog-Meat General,” who ruled Shandong for many years, fitted the stereotype. He was uneducated, a bandit by origin, loud-mouthed, cruel. His proudest “possession” was his large harem, in which there were women from China, Japan, Russia, and western Europe. He lived by violence, he lost his power by violence, and he died violently (after he had lost power), shot at the station of his former capital, Jinan.

Few warlords were as awful as Zhang. Some were progressive figures, complex men who blended self-interest with a genuine interest in the future of China. The most famous of this type was Feng Yuxiang, a mass of contradictions, blunt and devious, a personal power seeker and devout nationalist.

Other warlords were local strongmen who looked after their own regions, and in some cases gave them the most secure and stable periods of rule they were to know in many decades. In Shanxi, Yan Xishan, who ruled the province for more than three decades, is remembered as a model ruler; in Guangdong, Chen Jitang, who controlled the province for most of the 1930s, is considered a local hero; in Guangxi, the rulers of the province from 1925 to 1949, the “Guangxi Clique,” are revered for their martial spirit, which gave the province the name of “China’s Sparta.”

Tuzi buchi wobian cao. “The rabbit doesn’t eat the grass beside its nest.” Source: traditional

The better warlords understood the old proverb about a rabbit not eating the grass beside its own burrow, and they tended to show concern for the people of the region they controlled. They provided stable government, which, even though it came with tax swindling and rampant corruption, was preferable to chaos or anarchy. Tax income stayed in the region – except for the amounts that warlords salted away in Tianjin, Shanghai, or Hong Kong (cities under foreign control) – for the time when their rule came to an end.

The men referred to as “petty warlords” did the most damage to Chinese society. They really were bandits, uncouth and crude. They exploited and vandalized the regions they controlled. Their rule was often short. When they were overthrown by other warlords they went back to banditry or joined local militias.

The number of men under arms expanded dramatically in the early Republic. By the early 1920s there were at least 1.5 million soldiers, and an equally large number of armed men not serving in formal military units – irregulars, militiamen, bodyguards, and bandits. There was a two-way traffic between the organized and the informal armed worlds.

Warlordism had a strongly inhibiting effect on one aspect of Chinese society where there might otherwise have been change. The emancipation of women, which had just begun in China’s cities, was impossible in areas under indifferent or bad warlord control. Girls had to be protected by their families from the unthinkable – rape – and so many of them lived cloistered lives at home.

The warlord system provided immense numbers of jobs – either directly, as soldiers, or indirectly, in the manufacturing and service industries that catered to the military. The continuing growth of China’s population facilitated the expansion of the military. As the population grew, employment opportunities did not. Most of the jobs in the new factories were for young women. There were more and more young men in the rural areas for whom there was no work. A few could emigrate – to Manchuria, Southeast Asia or North America – but the closed nature of migration flows limited this solution to a few regions of China, all of them coastal.

Young men from regions with no established migration chains had only a few opportunities for off-farm employment – peddling, moving to the city, or going into the military.

Warlord finances

The foreign banks, like the concessions, contribute largely to the amenity of Chinese civil war and political strife. Once loot is turned into money and deposited with them by the looter, it is sacred and beyond public recovery. Cases have been known in which generals, far from expecting interest on their deposits, have been eager to pay the banks a small percentage for the privilege of being allowed thus to cache their gain. At a town up the Yangtze [Yangzi], a Chinese military commander visited the American- Oriental Bank and said that he wished to deposit with them, instead of in his own headquarters, what he politely called his records, and left thirty large trunks with the bank. He was presently defeated, and the bank manager was a little disturbed as to what he should do if the incoming conqueror were to demand that these records be handed over. But the in-coming conqueror felt equally insecure, and was more concerned to get his own records safely in to the bank than to obtain those of his enemy. Another huge batch of trunks was brought in, and the bank manager, much relieved, had both sets of trunks piled one beside the other.

Arthur Ransome, The Chinese Puzzle (London: Allen and Unwin, 1927), pp. 123–4.