Prior to the battle of Matapan, the Warspite picks up her Swordfish floatplane on the run. Illustration by Dennis Andrews.

The deteriorating military situation in Africa and Greece in 1941, however, made it clear that some offensive response by the Regia Marina was necessary if these theaters were to remain viable for the Axis powers. The Germans were now becoming more insistent that something be done to restore the situation in the Mediterranean. At their urging, and because of the general feeling at Supermarina (Italian naval headquarters) that an attempt should be made to re-establish the dynamics of conflict in the area, Operation Gaudo was born.

Vittorio Veneto firing upon Allied cruisers during the daytime phase of the Battle of Cape Matapan near the Island of Gavdos.

Supermarina committed the brand-new Littorio-class battleship Vittorio Veneto, sporting nine 15-inch guns and displacing 45,000 tons, as well as six of its seven 10,000-ton heavy cruisers and two of its best light cruisers to the operation. Usually reluctant to risk its capital ships, Supermarina had outdone itself for this mission. The Italians were further motivated by Luftwaffe reports on March 15, 1941, indicating that two of the three British battleships in the Mediterranean had been severely damaged and were not operational. Perhaps Supermarina officials would have been less sanguine had they known that those two battleships and their sister ship were not damaged, but anchored comfortably in Alexandria Harbor and quite ready to fight. Moreover, the British ships were led by one of the most competent and aggressive sailors in the Royal Navy.

Admiral Sir Andrew B. Cunningham, affectionately known as “ABC” to his men, had entered the Royal Navy as a cadet at age 14. While nurtured in a battleship navy, he was an early convert to air power. Cunningham had taken over a superb fleet whose training included night combat, which at that time was considered apostasy by most navies around the globe and ruled out as a matter of course. The British Mediterranean Fleet, however, excelled in night actions during prewar maneuvers and applied the lessons learned during the war years.

There were those in the Italian Naval Operational Command Centre (Supermarina). Admiral Riccardi, the Italian Chief of Naval Staff, and other leading members of the RMI, such as Admirals Campioni and Iachino, were particularly anxious to deliver a knock-out blow to Cunningham’s Mediterranean Fleet. There is more than a suspicion that they entertained and even cherished the thought of bringing about some form of massive set piece battle in which the British could be put to the sword in the Mediterranean – a type of new style Jutland with a different result from the original encounter in the North Sea. These ideas were all very well in theory, but the reality of the situation was what counted in Berlin and Wilhelmshaven. Appreciating that something needed to be done to improve its standing in the eyes of its Axis partner, Supermarina strove to orchestrate a plan (codename Gaudo) that would succeed in restoring some pride to the Italian Navy. One effective way of doing that would be to intercept and destroy a couple of lightly screened Allied convoys scheduled for late March: AG.9 en route from Alexandria to Piraeus and GA.9 going in the opposite direction. As John Winton suggests, it was an excellent plan which might well have succeeded had it not been discovered in advance.

Its secrecy was compromised to some extent by the Italians themselves. Their rather understandable eagerness in checking repeatedly on the location of the Mediterranean Fleet through increased surveillance patrols of both Alexandria and the convoy routes south of Crete in the days leading up to the launching of Gaudo certainly alerted Cunningham and his staff to the likelihood of some imminent action in the Eastern Mediterranean. These suspicions were confirmed by the latest ‘Ultra’ intercepts provided for the Admiralty by the members of Hut 6 (working on the Luftwaffe’s ‘Light Blue’ code) and Dilly Knox and Mavis Lever (who concentrated on the RMI’s ‘Alfa’ code) at Bletchley Park. This signals intelligence suggested that German exasperation at the Italian failure to deal effectively with the Allied convoys to Piraeus and Suda Bay was such that the Supermarina intended to send its main surface fleet south of Crete in search of the troop transports and supply ships that had so far eluded its submarine arm and that 28 March was scheduled as D-Day for this operation.

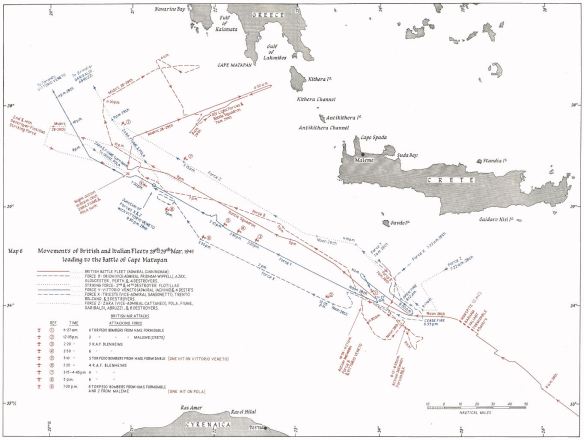

Forewarned of Admiral Iachino’s intended operational sortie off Crete, but not the composition of the force that would be undertaking it, the Admiralty swiftly re-routed and then recalled its two merchant convoys. If the Italians were spoiling for a fight, so was Cunningham. Risks had to be accepted in such a situation, but the prospect of doing real harm to the Italian Fleet was too good an opportunity for him to miss. He sought to make the most of his advantages by sending Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Pridham-Wippell’s Force B (four light cruisers and four destroyers) out from Pireaus to act as live bait for Iachino’s warships in the waters off Crete and lure them unwittingly into the steely embrace of Cunningham’s Force A (the carrier Formidable, three battleships and nine destroyers) coming up from the southeast. If this could be done successfully, Cunningham felt his warships could then set about the enemy with some gusto.

On the same day (27 March) that Pridham-Wippell’s Force B left port to get into its pre-arranged position south of Crete to begin trailing its cape for Iachino’s fleet to follow, the very ships it was hoping to attract rendezvoused south of the Straits of Messina and moved off south-eastwards towards Crete – and the convoy routes to and from Greece that lay further to the south. Although the RMI had no carriers to rely upon, the force that gathered in Sicilian waters was still quite impressive. Apart from his flagship the battleship Vittorio Veneto and four destroyers that had come from Naples, Iachino had gathered a fleet of six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and nine other destroyers from their bases at Taranto, Brindisi and Messina. It was a fleet that could have done an awful lot of damage to any Allied convoy it came across, but it lacked constant air cover and reconnaissance support. In the absence of a carrier, however, Supermarina had fully expected to have at its disposal the planes of Fliegercorps X operating from their base in Sicily – so the aerial deficiency was not regarded as being critical at this stage.

Whatever the Fliegerkorps might have done for the Italians, the fact remained that Cunningham was far better served by aerial reconnaissance than his opponents. At lunchtime on 27 March, an RAF flying boat based on Crete reported that three Italian heavy cruisers of the Trento class and a destroyer were at sea and heading towards the island. This report confirmed the accuracy of the earlier signals intelligence and convinced Cunningham that action was in the offing. Despite his aggressive instincts, he didn’t want to reveal his hand too soon lest the enemy fleet break off the operation and return to its home bases. Wishing to deceive Italian agents in Alexandria about his intentions to leave port and go out for a showdown with Iachino’s warships, Cunningham behaved ashore as if hoisting anchor was about the last thing on his mind on the evening of 27 March. What Michael Simpson describes as an ‘elaborate charade’ seemed to work perfectly. Force A left Alexandria after dark undetected by spies and sped towards its pre-arranged meeting with Force B south of Crete later in the morning of 28 March.

Over the course of the next thirty hours a fleet action that had promised so much for the Italians turned into another grievous defeat every bit as bad as the earlier Taranto débâcle, if not worse. Whether the Battle of Matapan deserves the ringing epithet of ‘a naval Caporetto’ given to it by the Italian critic Gianni Rocca is arguable, but what is clear is that it was a tragedy and one that had been largely, and sadly, self-inflicted. While aircraft and radar both had a critical role in assisting the British cause on 28 March, the stunning victory that would come his way after nightfall was gifted to Cunningham by his adversary Iachino. Aware from a lunchtime air raid that the Gaudo operation had already lost its surprise element, Iachino had opted for a safety-first policy by turning westward in a bid to put his ships beyond the range of what he assumed had been purely shore-based RAF units. Once the Vittorio Veneto had been hit and holed in the stern during a torpedo attack in the mid-afternoon, he could do no more than abandon the operation and – after sterling work by his damage control party – make course for home at the best possible speed. As the Italian Fleet limped westward it was spotted by one of Warspite’s reconnaissance planes and targeted again at dusk by both carrier and land-based aircraft. As luck would have it in trying to finish off the battleship an Albacore 5A, the last carrier plane to make an attack, succeeded in totally immobilizing the heavy cruiser Pola at 1946 hours. As she remained dead in the water, the rest of the fleet retired from the scene as hastily as possible. After exchanging a series of messages about the plight of the Pola and her crew with Carlo Cattaneo, one of his divisional commanders, Iachino made a gross tactical error at 2018 hours in sending back two other Zara class heavy cruisers and four destroyers to go to the aid of the crippled warship. While Iachino’s humanity cannot be faulted for trying to rescue her officers and men, the return of Cattaneo’s entire group to retrieve the Pola by towing her to safety when he knew by this time that the Mediterranean Fleet was at sea is simply unfathomable. One can only imagine he thought the British ships weren’t close enough to be an active threat during the hours of darkness and that by morning he would have arranged sufficient air cover for Cattaneo’s entire group that Cunningham wouldn’t dare to intervene. It was an egregious error. Iachino may have thought that the British wouldn’t risk engaging in any night fighting, but if he did he didn’t know his opposite number. Cunningham was determined not to let the battleship get away and was prepared to bring the enemy fleet to action in the dark if need be, even though his ships had not practised night fighting for some months and the skills necessary to become good at it still remained rudimentary at best.

In the end, of course, the night action that took place didn’t involve Iachino’s entire fleet, but just Cattaneo’s division of it. They had the wretched luck to return to the stricken Pola just when Cunningham arrived at the same spot with Force A. Martin Stephen describes the scene graphically: ‘With flashless cordite and radar the British were sighted men in a world of the blind.’ At what amounted to point blank range the result was never in doubt. Fiume and Zara were soon rendered into smoking hulks by the broadside they received. In a little over four minutes the Zara class of heavy cruiser had, for all practical purposes, ceased to exist. As Cunningham described it later it was ‘more like murder than anything else’. Removing his battlefleet from what Barnett describes perfectly as a ‘chaotic mêlée’, Cunningham left his own destroyers to deal with their Italian equivalents. During the course of the evening, two of the four enemy destroyers were sunk (Alfieri and Carducci) while Oriani was damaged but managed to escape along with the unscathed Gioberti.

It was a magnificent victory for Cunningham, but it might have turned out even better had he not sent a sloppily phrased signal to the rest of his ships shortly after putting the heavy cruisers out of action that seemed to imply that all those not engaged in dealing with the enemy should withdraw to the northeast. While the ambiguous message was not intended for his light cruiser squadron, Pridham-Wippell didn’t realise that at the time. He broke off his pursuit of the Vittorio Veneto and withdrew to the northeast to conform with his C-in-C’s apparent orders. By the time that Cunningham had become aware of what had happened, Iachino’s flagship and her accompanying warships had escaped to live and fight another day. That was more than could be said for Vice-Admiral Cattaneo and 2,302 officers and men of the Regia Marina who perished in these engagements. Correlli Barnett calls it ‘the Royal Navy’s greatest victory in a fleet encounter since Trafalgar’. Is it churlish to suggest that it could have been even greater? It might well have been but for the ambiguously worded signal Cunningham had sent while basking in the glow of his battlefleet’s destructive blitz against Cattaneo’s heavy cruisers. Michael Simpson, the editor of Cunningham’s papers, draws another valid conclusion about the Battle of Cape Matapan, namely, that the C-in-C would have been far better served had he had two carriers rather than only one with him on this operation. Extra aircraft would have given him far more systematic reconnaissance and firepower than was available to him from only having Formidable and some of the land-based RAF torpedo-bombers at his disposal.

One thing that all the leading naval analysts who have reviewed the action off Cape Matapan agree upon is that this crushing defeat for the Regia Marina was as much psychological as it was material. It dealt a real blow to the esteem in which the Italian fleet was held and made the Supermarina far more cautious than it otherwise might have been. This attitude of restraint was further reinforced by yet another rout its forces suffered at the hands of the British only a few days later in the Red Sea, in what became an ultimately fruitless Italian quest both to attack Port Sudan as well as to retain their base of Massawa on the coast of Eritrea. In the face of a sustained land and aerial offensive launched by the enemy which closed in on the port on 6 April and captured it two days later, the Italians would lose six seaworthy destroyers, a torpedo boat, five MAS (fast motor torpedo boats) and nineteen of their merchant vessels, while six German ships, including the passenger ship Colombo, suffered the same fate. Somehow the degree of hopelessness into which the Italian naval cause had sunk was typified by the scuttling of the vast majority of these craft by their own crews at a total cost of 151,760 tons.