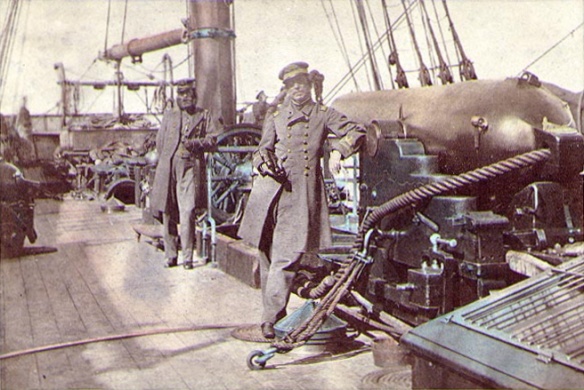

Captain Raphael Semmes, CSS Alabama’s commanding officer, standing by his ship’s 110-pounder rifled gun during her visit to Capetown in August 1863. His executive officer, First Lieutenant John M. Kell, is in the background, standing by the ship’s wheel.

The USS Kearsarge, right, sinking the CSS Alabama off the coast of France in 1864. Painting by Jean-Baptiste Henri Durand-Brager, 1814-1879.

The most famous of the Confederate commerce raiders during the 1861-1865 U. S. Civil War. Built by John Laird & Sons at Liverpool, England, and launched in May 1862 as the Enrica, she was outfitted in the Azores, where in August Captain Raphael Semmes placed her into commission as the CSS Alabama.

A sleek, three-masted, bark-rigged sloop of oak with a copper hull, the Alabama was probably the finest cruiser of her day. She weighed 1,050 tons and measured 220′ x 31’9? x 14′ (depth of hold); she could make 13 knots under steam and sail, and 10 knots under sail alone; and she had a crew of 148. She mounted 6 x 32-pounders in broadside and two pivot-guns: a 7-inch 110-pounder rifled Blakeley and a smoothbore 8-inch 68-pounder amidships.

During the period of August 1862 to June 1864, the Alabama cruised the Atlantic, Caribbean, and Pacific all the way to India. She sailed 75,000 miles, took 66 prizes, and sank the Union warship Hatteras. Twenty-five Union warships searched for her, costing the federal government over $7 million. Her exploits had been a considerable boost to Confederate morale.

Semmes knew his ship was badly in need of an overhaul, and he sailed her to Cherbourg, France. Cornered there by the Union steam sloop Kearsarge, on 19 June 1864 Semmes took his ship out to do battle. In one of the most spectacular of Civil War naval engagements, the Kearsarge sank the Alabama.

In 1984 the French navy located the Alabama within French territorial waters. British preservationist groups wanted the wreck, if raised, to be displayed at Birkenhead, where she was built. The U. S. government asserted ownership, however, and in 1989 Congress passed a preservation act to protect the wreck.

Alabama Claims

Claims by the United States against Britain for losses suffered at the hands of the Confederate raiders by Northern shipping during the 1861-1865 U. S. Civil War. As early as November 1862, the U. S. government had filed claims with the British government for these losses. After the Civil War, the fact that London had allowed the fitting out of the Alabama and other Confederate cruisers became a major stumbling block in Anglo-American relations. Washington believed, rightly or wrongly, that London’s persistent disregard of its own proclamation of neutrality had heartened the South and prolonged the conflict.

Charles Sumner, the powerful chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, asserted that Britain owed the United States half the cost of the war, or some $2.5 billion. He proposed that the United States take British possessions in the Western Hemisphere, including Canada, as compensation.

Little was done to meet U. S. demands for compensation until 1871, when Germany defeated France. With the European balance of power decisively changed, statesmen in London believed it might be wise to reach some accommodation with the United States against the possibility of a German drive for world hegemony. London proposed establishment of an arbitration tribunal.

Consisting of five representatives-from Britain, the United States, Brazil, Switzerland, and Italy- the tribunal met in Geneva beginning in December 1871 to hear and determine “claims growing out of the acts committed” by the Alabama and the other Confederate commerce raiders fitted out in Britain, “generally known as the Alabama claims.” The commission did throw out Washington’s demands for indirect claims, such as for expenditures in pursuit of the cruisers, the transfer of U. S. shipping to British registry, and any prolongation of the war. Nevertheless, on 14 September 1872 the tribunal awarded the U. S. government $15,500,500. A special U. S. court was then set up to disperse the funds, and it ultimately awarded $9,416,120.25. Another claims court made payments beyond those cases covered by the Geneva tribunal. What money remained was used to refund premiums paid by shippers for war insurance. Direct losses were indeed paid in full and insurance charges were prorated.

The Alabama claims settlement has come to be regarded as an important step forward in the peaceful settlement of international disputes, and a victory for the rule of law.

Kearsarge (U. S. Navy, Screw Sloop, 1862)

U. S. Navy screw sloop, one of the most famous ships of the Civil War (1861-1865). The Kearsarge was the second in the two-ship Mohican-class. Her sister entered service in 1859. Commissioned in January 1862, the Kearsarge was 1,550 tons, 198’6? (between perpendiculars) x 33’10? x 15’9?, and bark-rigged, and she mounted 2 x 11-inch Dahlgren smoothbores in pivots and 4 x 32-pounders in broadsides. She also mounted a 1 x 30-pounder rifled gun and had a small 12-pounder boat howitzer (the latter not included in her official armament). Her complement was 160 men. The Kearsarge was in the European Squadron from 1862 to 1866. In June 1864 she was off Calais keeping tabs on the Confederate ships Georgia and Rappahannock when word was received that the Alabama was at Cherbourg.

Captain John A. Winslow and his well-trained crew had spent a year searching for the Alabama, and he was determined that she would not again elude him. The Kearsarge was soon under way. Two months out of a Dutch dockyard and in excellent condition, she arrived at Cherbourg on June 14 and quickly located the Alabama. The Alabama’s captain, Raphael Semmes, elected to fight, and the battle occurred on 19 June 1864, in the English Channel. It was one of the most spectacular of Civil War naval engagements. Despite Semmes’s later claims that the Kearsarge had the advantage in size, weight of ordnance, and number of guns and crew, the two ships were actually closely matched. The Kearsarge’s 11-knot maximum speed made her slightly faster than her opponent, and her broadside weight of metal was about a quarter greater than that of her opponent (364 lb. to 274). Winslow also had ordered chain wrapped around the vulnerable parts of his ship. During the battle Winslow outdueled Semmes, but he was fortunate that a shell from the Alabama, which lodged in the Kearsarge’s wooden sternpost, did not explode.

The Kearsarge enjoyed a long service life, succumbing only to shipwreck off Central America on 2 February 1894.

Raphael Semmes, (1809-1877)

Confederate navy officer and captain of the cruiser Alabama. Born on 27 September 1809 in Charles County, Maryland, Raphael Semmes was raised by relatives in Georgetown, District of Columbia, after the death of his parents. In 1826 he won a midshipman’s appointment. Promotion was slow, and it was 1837 before he made lieutenant. In long leaves of absence ashore, Semmes took up the study of law, a profession he followed when not at sea.

From 1837 until the Mexican War Semmes spent most of his time on survey work along the southern U. S. coast and in the Gulf of Mexico. Early in the Mexican War he commanded the brig Somers. In December 1846 she sank in a sudden squall off the eastern coast of Mexico. Half of her crew were lost, but a court-martial found Semmes blameless. In March 1847 he took part in the capture of Veracruz; later he participated in the expedition against Tuxpan and, accompanying land forces to Mexico City, was cited for bravery. After the war he again found himself in a navy with too many officers and spent much of his time on leave. In 1852 he published Service Afloat and Ashore during the Mexican War. Promoted to commander in 1855, the next year he joined the Lighthouse Board.

Semmes had moved his permanent residence to Alabama, and, following that state’s secession and creation of the Confederate States of America, in February 1861 he resigned his U. S. Navy commission and the next month entered the Confederate Navy as a commander. Sent into the North, he purchased military and naval supplies and equipment. In mid-April Semmes met with Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory and secured command at New Orleans of the Sumter, the first Confederate commerce raider. Between June 1861 and January 1862, Semmes took 18 Union prizes until, his ship in poor repair and blockaded by Union warships, Semmes abandoned her at Gibraltar.

In August 1862 the Confederate Congress advanced Semmes to captain, and Mallory gave him command of a new ship nearing completion in England. Semmes named her the Alabama. For nearly two years the Alabama ravaged Union shipping. Through July 1864 she took 66 prizes and sank a Union warship, the Hatteras. In all, Semmes took 84 Union merchantmen. He estimated that he had burned $4,613,914 worth of shipping and cargoes and bonded others valued at $562,250. Another estimate placed the total at about $6 million.

Semmes finally put into Cherbourg, France, with the Alabama for repairs, but French officials rejected his request to use the dry dock there. On 19 June 1864, Semmes sortied to engage the Union steam sloop Kearsarge. In the ensuing battle the Kearsarge sank the Alabama, but Semmes escaped on an English yacht.

Semmes then made his way to Richmond via the West Indies, Cuba, and Mexico. Promoted to rear admiral in February 1865, he commanded the James River Squadron of three ironclad rams and seven wooden steamers. When Confederate forces abandoned Richmond on 2 April, Semmes destroyed his vessels. The men of the squadron then formed into a naval brigade under Semmes as a brigadier general. He surrendered at Greensboro, North Carolina.

Paroled in May 1865, Semmes returned to Mobile. Arrested in December, he was transported to Washington and held there for three months to await trial on charges he had violated military codes by escaping from the Alabama after her colors had been struck, but he was released when the Supreme Court denied jurisdiction. He was then briefly a probate judge, a professor at Louisiana State Seminary (now Louisiana State University) at Baton Rouge, and a newspaper editor. Political pressure cost him all three positions. Following a profitable lecture tour, he resumed the practice of law. In 1869 he published Memoirs of Service Afloat, during the War between the States. Semmes died at his home in Point Clear, Alabama, on 30 August 1877.

References: Semmes, Raphael. Memoirs of Service Afloat, during the War between the States. Baltimore, MD: Kelly, Piet & Co., 1869. Reprint, Secaucus, NJ: Blue & Grey Press, 1987. Taylor, John M. Confederate Raider: Raphael Semmes of the Alabama. Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 1994. Tucker, Spencer C. Raphael Semmes and the Alabama. Abilene, TX: McWhiney Foundation Press, 1996. Sinclair, Arthur. Two Years on the Alabama. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1895. Robinson, Charles M., III. Shark of the Confederacy: The Story of the CSS Alabama. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995