The increasing resistance of English armored formations at Marsa el Brega was broken on 1 April by the attacks of the 5. Leichte Division. The Marsa el Brega area was a bottleneck, extending 13 kilometers between the dunes arrayed along the sea and the salt seas [to the south] that were difficult to negotiate by heavy vehicles. While Panzer-Regiment 5, supported by MG-Bataillone 2 and 8, advanced further along either side of the Via Balbia, our armored scout sections chased away English patrols along the sea and in the dunes. The motorcycle infantry company of [the battalion] was employed in the area between the sea and the Via Balbia. Widely dispersed, we went on the hunt across the largely dry salt seas and engaged English pockets of resistance. Generally, the resistance was slight. The English infantry mounted up on trucks that had been prepositioned and pulled back to Agedabia. A few English trucks got bogged down in the salt flats in the process; the mounted infantry was captured . . .

After his initial period of acclimation, Schroetter describes the routine of reconnaissance in the desert:

After their defeat in June 1941, the English pulled way back into Egypt. There was only a screen of armored reconnaissance sections left behind to observe.

For their part, the Germans also positioned armored scout sections to screen along the Egyptian-Libyan border. The two reconnaissance battalions, Aufklärungs-Abteilung 3 and Aufklärungs-Abteilung 33, swapped out their scout sections arrayed in front of the strong-points every 14 days.

The following areas were designated as observation points: Point Bir Nuh; Point 205 (Sidi Suleiman); Point 204; and Point 200 (Fort Sidi Omar)

The armored reconnaissance sections were assigned one of those points, from which they had to conduct constant surveillance to their front. Small raids were allowed, but the mission dictated that the sections were not to allow themselves to be driven from their assigned points: Observe a lot; if necessary, fight; withdraw quickly and agilely, so as to show up in the flanks or rear at some other point. The “standing patrols” were required to be able to give information concerning the situation to their front at any time.

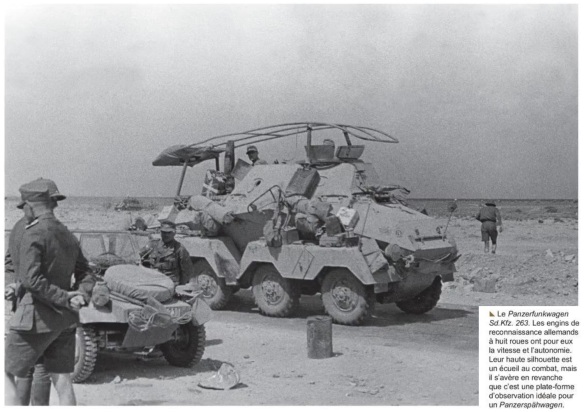

During that period—the beginning of September 1941—I was transferred to the 2nd Company, the armored car company [of the battalion]. I took over a light armored scout section. It consisted of three light armored cars, each weighing 4 tons. Two vehicles were outfitted with a 20mm automatic cannon and a machine gun; the third vehicle, a radio car, had the necessary radio equipment (40-watt transmitter) and a machine gun. All of the vehicles had all-wheel drive, with the front axle capable of being disengaged. All four wheels could also be engaged for turning.

So equipped, the scouting section was very agile and capable of cross-country movement. It was also extremely fast. In soldier jargon, they were like rabbits: The vehicles were too fast up front and too short in the rear to be knocked out. As a result of the low silhouette, the vehicles “disappeared” in the landscape; they were especially difficult to make out at long range.

The crew in the vehicle with the 20mm cannon consisted of the vehicle commander (also the patrol leader in the first vehicle), a gunner and a driver. In the radio vehicle, the crew was a vehicle commander, a radio operator and a driver. The vehicle commander also serviced the weapon.

When the missions were assigned, my section was given Point 205, the house ruins at Sidi Suleiman. As far as Capuzzo and around Sollum, I knew the terrain well from my previous operations. Nonetheless . . . what could I expect there?

I was being employed for the first time as the leader of an armored scout section. As the leader of a motorcycle infantry platoon, I was always connected to the company. Now I was on my own and responsible for an additional eight soldiers, whose well-being was dependent on my actions.

I reported to the commander and departed, moving along the Via Balbia in the direction of Capuzzo, the desert fort that had been so hotly contested. From there, we went in the direction of Sidi Suleiman, our objective.

Sidi Suleiman, a set of house ruins on top of a jutting piece of high ground, was a distinctive terrain feature. When there was good visibility, you could see from Hill 205 far out into the descending plain to the high ground almost 10 kilometers distant. The English scout sections were positioned there.

The lead of the scout section being relieved briefed me on the situation. There wasn’t much to be identified in the midday air that glimmered in the heat.

The English were on the high ground to the east and reconnoitered in the morning and the evening into the plains below. My predecessor recommended I do the same. He then disappeared to the west with his armored scout section, wrapped in a cloud of dust.

I checked out the immediate environment. We followed the tracks made by my predecessor. They provided information about his activities. In the light of the setting sun—it was to my back—I saw the clouds of dust being churned up by the vehicles of my English “colleague.”

I ventured towards him, somewhat cautiously, since I still did not know the terrain.

At a distance of about two or three kilometers—not a great distance for Africa—we faced each other. The English armored cars could be made out quite clearly in the evening sun. They were vehicles of a type we had not yet encountered.

We observed one another, the vehicles widely dispersed.

But what was the man in the vehicle in the middle doing? It was most likely the section leader. All of a sudden, the Englishman stood up on his vehicle and waved to us. Those English were sure polite. Standing on my vehicle, I also waved a friendly “good night” to him. A few artillery rounds impacting in the vicinity soon brought us back to reality. As night descended, we each pulled back to our respective high ground, one to the east and the other to the west.

We set out outposts around Sidi Suleiman and transitioned to nighttime rest. The stillness of the desert spread out before us. Not a sound was to be heard. The pale moon weakly illuminated the terrain in front of us.

At first light—it was around 0550 hours—we crawled out from under our blankets. The vehicles had to be warmed up. There was nothing to be seen of our Englishmen. We searched the horizon in vain for them. It wasn’t until around 0700 hours that we caught a glimpse of them on the eastern heights.

You could tell which scout section it was by the way they deployed. The one section leader kept two vehicles close together and positioned the third one somewhat off to the side. The other leader had his vehicles dispersed at exact intervals from one another. A third one kept two vehicles up front and the third one somewhat to the rear. Each of those sections received a corresponding nickname from us.

In the glimmering morning sun, which put me to a great disadvantage when observing to the east, we met in the plain. Once again, the Englishman stood on his vehicle and waved a friendly “good morning” to me. I replied in kind. Once again, there were artillery rounds in the vicinity, followed by a withdrawal by both sides to their respective high ground.

In the heat of the day, observation was very limited by the glimmering air. It took a trained scout’s eye to make out the three enemy armored cars in the mirage. The camel thorn bushes, which had taken on the appearance of “woods,” had three thin fir trees spiking out of them.

All of a sudden, an artillery round landed in Sidi Suleiman. Thank God we had always avoided that distinct feature during the day.

But who was that single round intended for? It was a single round . . . nothing followed. By chance, I looked at my watch. It was exactly 1200 hours, noon . . .

We couldn’t figure it out. From that time forward, we received that single round every day at the same time.

It goes without saying that the English took pains to prevent our forces from getting a glimpse into the area south and east of the general lines they occupied. As a result, our scout sections were frequently faced by three or more English patrols. As already described, the English often employed forward observers to direct the artillery employed behind the reconnaissance veil. Whenever reinforced patrols of the Germans advanced, the line of English scout sections would pull back like a wire screen. The enemy would then defend with artillery fire and self-propelled antitank guns, which were attached to the (English) scouts. They were also supported by low-level attacks by English fighters.

My first 14 days at the front as the leader of an armored scout section came to an end. It had been marked by mutual suspicion and lurking, by morning and evening “greetings” to one another that we both participated in and by the noontime impact of a single round on Sidi Suleiman.

Unlike the European theater, scouting sections frequently conducted operations at night:

Late in the afternoon of 17 December [1941], we were positioned with three scout sections in an area marked by high plateaus, deep defiles and flat wadis. It was an extremely broken piece of terrain in the area around Signali, south of Derna.

Aufklärungs-Abteilung 3 (mot) had the mission to occupy a new position far to the west in the vicinity of Mechili. A battle group left behind by the Battalion Commander had withdrawn from its delay position and was on the march in that direction. Widely dispersed, only our armored scout sections were holding the position. All around us, we identified advancing English vehicles. Truck columns, increasing in number, advanced in our direction. It was a sign that the enemy was feeling confident. We were already in danger of being bypassed when the order to withdraw reached us around 1700 hours. It was both a surprise and a relief. We assembled and moved out to the west through a wadi. The three armored scout sections had a total of nine 4-wheeled armored cars. Moving along the Tregh Enver Bey, we reached a plain around evening that offered good visibility.

As the evening sun was setting, we suddenly saw a column of English vehicles, tanks and artillery, crossing our path ahead of us. They were moving from south to north.

At first, we hoped that they were captured vehicles, but a radio inquiry to battalion revealed that we had English in front of us!

We debated what we should do. Should we wait until the enemy formation had moved further north? But it did not appear to be continuing its march. We could also see that additional units were closing in. We thus decided to wait until it was night and then attempt to break through. We observed the enemy formation, which had halted in the meantime. Around 2200 hours—the moon had not yet risen—we started to move out, one scout vehicle behind the other, nose to tail, in an effort not to lose contact with one another. We tensely paid attention to the vehicle in front of us. On the first vehicle, I was positioned on the fender in order to give the direction and direct the driver. On the other fender was my radio operator, who was supposed to reply to any challenges by English guards.

In the course of that night march—the drivers could hardly see their hands in front of their faces—the vehicles had to tolerate a lot. They bounced over gravel and piles of rocks. The drivers had to hold the steering wheels firmly in their hands. The commanders of the individual vehicles observed the route and the terrain from their turrets.

“A little more to the left . . . a little bit more . . . now some to the right . . . now straight . . . slow . . . just a tad left . . .”

So went the night.

We slowly snuck up to the resting English column. We saw the first few tanks and trucks in front of us. A guard called out to us. The answer my radio operator gave appeared to satisfy him. They didn’t appear to think there were any German soldiers in this area.

We got through the first “enemy contact” successfully. But we were still worried: Did everyone make it? Did a vehicle lose contact?

We were surprised that there was no enemy resistance. Didn’t the English realize what was happening? A column of armored vehicles certainly had to stand out! They seemed to feel safe, and the darkness of the night helped us on the one hand not to be discovered, even if it made life difficult for us on the other. We carefully and slowly pushed our way through the English vehicles that were all around us. We passed by the small tents that had been set up for the sleeping crews and went by artillery pieces, tanks, trucks and antitank guns. It wouldn’t be too long, it seemed. The massing of the vehicles was decreasing. We approached the outer edge of the English march column. None of the English guards had heretofore expressed any suspicions. It was not until the last vehicle of our column had left the English formation and was headed west, when one of the guards had second thoughts and fired a signal flare in our direction so as to better see who was “taking a Sunday drive.” We had reached the open desert by then and disappeared into the night, when some rounds were fired in our direction.

All alone on the battlefield, the scout sections often charted their own destiny. Initiative, confidence, and tactical ability were all in great demand when separated by great distances from the main body of friendly forces or defensive lines:

We soon encountered English patrols in that terrain, terrain that practically invited you to play a game of “Cat and Mouse.” The fact that they were there was determined from the vehicle tracks.

As a scout section leader, who had participated in uninterrupted operations for several months, you not only got a sense for terrain but for tracks. The depth, to which the tires of the vehicles had pressed into the ground, the degree of blowover from the sand and the direction of the tread of the tires told us who, when and in which direction the tracks had been left. The tracks we saw came from English armored cars that had to have passed through there that morning. We needed to be careful! The English could still be nearby.

Soon we were receiving enemy machine-gun fire from a dschebel [hill, derived from the Arabic] in front of us. Seeking cover behind another plateau, we tried, for our part, to get behind the English. The hunt on the plateaus had started. Sometimes, we suddenly saw the enemy in front of us. He appeared to be lurking for us around a corner. Other times, he was suddenly to our rear. We chased each other around the plateaus, engines racing and constantly being on alert. But neither party could deliver a decisive blow, even though a few machine-gun rounds ricocheted off the armor of my armored car.

Our mission required that we shake off the English. They lost sight of us.