Over time, most western European countries engaged in wars with one another, forming assorted alliances, settling old scores, and always looking for ways to gain wealth, power, and land. Fought on North American soil, the French and Indian War (1756–1763) pitted the British against the French and their Native American allies in an extension of hostilities between the two nations that also played out in Europe and on the high seas.

The British wanted to drive the French from North America. After many successes by the French forces in the Ohio Valley and in Canada, the tide of the war changed when William Pitt became England’s new secretary of state and adapted English battlefield tactics to fit the New World terrain and environment. In addition, some of the Native American tribes changed sides and fought with the British. The French found themselves with two outposts: Fort Carillon (later called Ticonderoga), in upstate New York, and the city fortress of Québec. When Carillon fell to British forces, Pitt’s men turned their attention to Québec, an “almost impregnable fortress” on the cliffs of the St. Lawrence River.

The generals in charge of both armies were highly decorated soldiers. General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, a career soldier, commanded the French troops in the fortress. His opponent, General James Wolfe, was fresh from an inspired victory over the French at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, off Canada’s Atlantic coast.

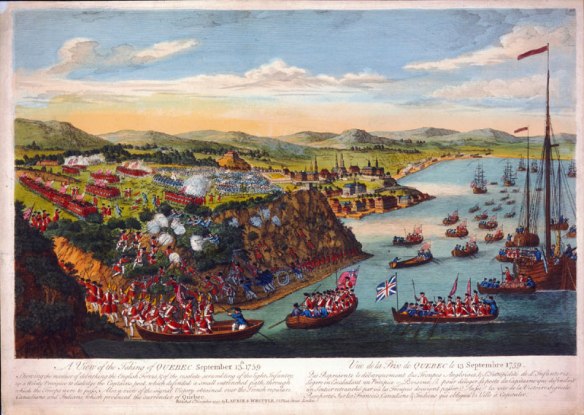

The armies were evenly matched with about 4,500 to 4,800 soldiers each. The French, however, had several advantages. First, they were stationed safely within the walls of the city, perched on a fifty-foot cliff overlooking the St. Lawrence River. Second, the weather favored the French, who believed that they could wait out the British. With winter approaching, threatening to ice over the river, the British would not be able to keep their ships in the water much longer. And with the British ships gone, supplies would again flow freely to the garrison at Québec. Wolfe knew he had to do something to draw Montcalm from the fortress. If he could meet the French army on an open field, he believed that his highly trained, veteran army would easily defeat the French, who were mostly militia forces.

In Wolfe’s first attempt to draw the French out, he landed his troops at Point Levis, on the south bank of the St. Lawrence, opposite Québec. He began a bombardment of the fortress, hoping that it would force the French to leave. Although “most of the lower town was destroyed, Montcalm would not be drawn Wolfe’s next effort also failed to achieve the result he wanted. He landed some troops upriver of Québec, hoping that this would draw troops from the garrison. Montcalm did send out six hundred men, but only to guard the paths from the river to the fortress. With French soldiers now protecting the paths, Wolfe’s men would never be able to reach the top of the cliffs.

Then British scouts returned with news. There was a small French camp at Anse-au-Foulon, about a mile and a half west of the city. With this intelligence, Wolfe believed that he could now use a deception strategy sometimes called “uproar east, attack west” to lure the French into a battle that would be their undoing.

He ordered Admiral Charles Saunders to move the British fleet to a position opposite one of Montcalm’s main camps east of the city. The fleet needed to give the impression that it was preparing for an attack. Montcalm fell for the demonstration deception, moving troops to guard against a British assault from that point in the river.

In the meantime, Wolfe launched his main action. He sent a small “band of eager volunteers” ashore near Anse-au-Foulon and eliminated the soldiers encamped there. Now one of the roads to the heights near Québec was open, and Wolfe brought as many troops as possible up it. Before long, he found the open field he had been hoping for: a farmer’s field just west of Québec that would become known as the Plains of Abraham. In the early morning, he deployed 3,300 regular soldiers in two lines that stretched across the field for a little more than half a mile. His instructions to his men were emphatic: do not fire until the French are within forty paces. This time the French did come. Alerted by a French soldier who had escaped the assault at the camp, Montcalm marched his troops to face the British on the Plains of Abraham. As one historian wrote, “It was a time to defend not to attack. . . . But Montcalm did exactly what Wolfe wanted.” He put his undisciplined soldiers against the professional soldiers of King George.

The British held their fire as the French approached. Wolfe had ordered his men to charge their muskets with two balls each in preparation for the engagement. Some of the French soldiers fired random shots. Then the British line launched a withering volley, instantly cutting down many of the French soldiers. The British soldiers stepped forward a few paces before unleashing another deadly volley at the stunned enemy. The British pressed on, firing as they advanced. More French fell. The army was “disintegrating, falling back in disorder into the town.” Wolfe’s success came at a high price: both he and Montcalm were mortally wounded in the battle. Wolfe died on the battlefield; Montcalm died in Québec that night.

The fall of Québec was the turning point in the French and Indian War, and it was Wolfe’s deception that gave the British the opportunity they needed to defeat the French. One historian calls it “one of the most momentous battles in world history” because it drove the French from the territory that was to become Canada and “produced the political circumstances in which the United States of America emerged.”