In earlier wars, such as the American Revolutionary War and the Civil War, deception was generally the brainchild of a single person, usually the battlefield commander, who had to implement covert operations in the heat of combat. But World War I, “the war to end all wars,” brought a clear shift in the role of deception by the military. Deception tactics and strategies became institutionalized and played a larger part in planning. In England, decisions about deception were made by the War Office in London, and its efforts to use camouflage became one of the first organized attempts at deception in battle. The British military grew to be particularly adept and avid users of camouflage. In a sense, they wrote the early version of the “book” on deception, although they did get a bit of help from their French allies.

By December 1915, World War I had been raging for more than a year, and the United States was still more than a year away from joining the Allies to fight the Central Powers. The British War Office arranged for painter Solomon J. Solomon to sail to France to learn what a group known as the camoufleurs was doing and to determine if the British army should create its own camouflage unit.

At Amiens, France, Solomon found a group of artists who were “working out the right colors for disguising and screening and also making realistic dummies, including armored trees for use as observation posts.” French observation posts near the front lines could be used to direct British artillery strikes; in order to be most effective, they needed to be as close to the front as possible — and so needed to be well concealed. General H. E. Burstall, commander of Canadian artillery, asked Solomon if he could aid the French efforts by designing and making forward observation posts — OPs, also called Oh Pips — disguised as trees. Solomon accepted the challenge and returned to England to work with a team of “sappers,” or combat engineers.

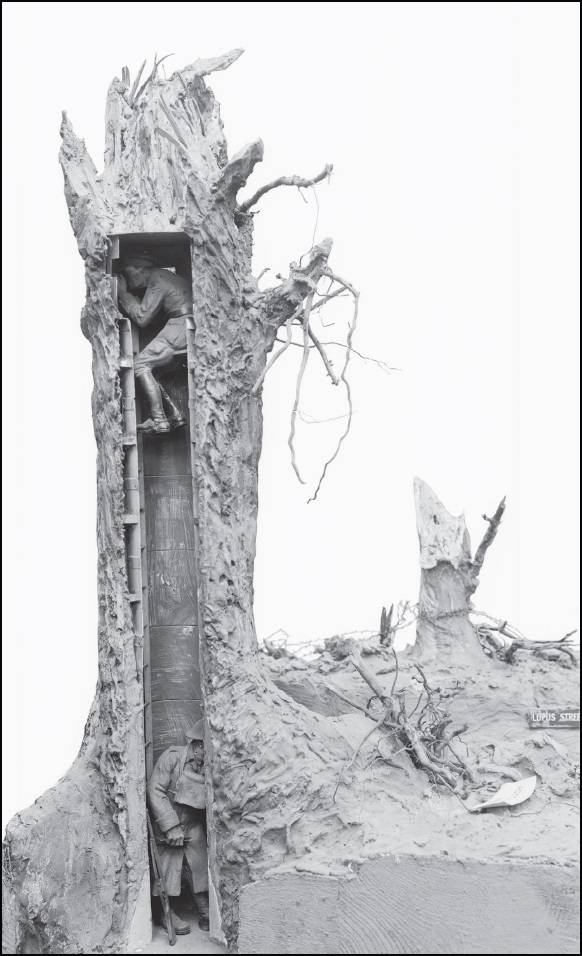

Solomon’s trees were made of oval steel cylinders, constructed in two-foot sections. They were just wide enough for a man to work his way up inside the structure to a folding seat near the top. From there, ten to fifteen feet above the ground, he could observe every activity through holes or slits. While the basic design was suitable, Solomon knew that in order to be properly concealed, the Oh Pips needed bark to make them look more like real trees.

Solomon decided that a good source of bark was the forest around King George’s royal estate at Windsor Castle, so he wrote to the king for permission to take bark from a decayed willow tree. “Secrecy in the affair,” he wrote, “is of the highest importance.” He was correct, of course, in believing that it was better to ask the king for the bark rather than to trust the discretion of a private citizen. The king’s secretary replied from Buckingham Palace that “the King will be glad to give you every facility you require either at Windsor or at Sandringham.” With the help of two scene painters and a theatrical prop maker, Solomon fashioned tree cover that would pass for real bark when viewed from a distance. He sewed chunks and strips of bark to sheets of canvas that would then be wrapped around the trees’ steel shell.

On March 15, 1916, the first tree was erected. Solomon’s trees and other versions of the camouflage tree saw action on the battlefields of Europe, where they served their purpose well. A 1917 issue of Popular Mechanics featured a picture of a steel tree, noting that “a structure of this sort standing amid tree trunks that have long survived artillery fire is almost sure to escape detection by the enemy.” Another version found in Belgium was nearly eighteen feet tall, with “‘lumps’ on the outer shell, made of chicken wire and grass like materials to resemble either burls or lumps of moss or lichen. . . . The ‘bark’ . . . appears to include crushed sea shells to give it a rough texture.” Regardless of the construction of these steel trees, their purpose was the same: deceiving one’s enemies to gain an advantage over them.

With the Oh Pips designed, the British camoufleurs’ work was only beginning. On January 18, 1916, Solomon and his team — a draftsman, a scene painter, a property man from a theater, and a master carpenter — sailed to France and set up shop in Amiens. They spent a week studying what their French counterparts had done and then got to work.

Solomon was not content with merely creating camouflaged Oh Pips. He saw other ways that camouflage could be improved to deceive the Germans and their allies. One area that the painter felt needed attention was the covering that protected the trenches. It was common to use mackintosh sheets, a waterproof covering similar to a tarp, over the trenches. But the sheets collected pools of water, making them unwieldy and heavy. And, looking at them with the eyes of a painter, Solomon thought that the pattern painted on the sheets was too smooth and didn’t match the surrounding terrain.

As an alternative, Solomon tried using string to make a “cat’s cradle” that he envisioned could be covered with leaves and branches, making a more lifelike camouflage. His prop man took over and in short order wove a square yard of netting. Solomon was the first to implement the use of fishing nets instead of canvas as a camouflage for trenches — as well for guns, supplies, and ammunition stores.