Early Fortifications

Although fortifications were constructed in Japan prior to the feudal period, frequent conflicts associated with warrior ascendancy inspired new, distinctive temporary architectural forms as well as more lasting structures to protect against military attack.

Up to the beginning of the feudal era, three forms of fortifications were built, according to archaeologists. The grid-pattern city form was inspired by Chinese planning precedents, and included gates or walled enclosures. Mountain fortresses appear to be an indigenous form, and were typical of remote areas. Plateaus or plains often utilized the palisade, a semi-permanent defense. Typical defenses included a rampart, a ditch, and a palisade. Grid-pattern cities were surrounded by walls that served as a demarcation point rather than as true protection, and eventually such barriers disappeared. Remains of mountain fortresses found in northern Kyushu were a more effective means of protection, and may have belonged to ancient kingdoms that ruled parts of Japan in early times. Palisades were often constructed in the northeastern areas of the main island of Honshu. Although excavations have revealed only partial remains of such structures, they are significant since they offer prototypes for medieval fortifications.

Until the end of the Kamakura period, most fortresses built in Japan were relatively simple, and were designed for a particular siege or campaign. Terms such as shiro and jokaku (translated in later eras as “castle”) appear frequently in 12th- and 13thcentury accounts of warfare, but in the Kamakura era, these terms refer to temporary fortifications. Early medieval defense structures were more like barricades than buildings, and were not intended to house soldiers for extended periods. However, such fortifications could be elaborate and large in scale.

Many extant screens depict scenes from Tale of the Heike, the famous Japanese historical saga of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Its twelve volumes relate the long narrative of the rise and fall of two rival warrior clans, the Genji (or Minamoto) and the Heike (or Taira). This screen illustrates famous episodes from the saga, including the battle at Ichi-no-tani Mountain and the death of Taira no Atsumori at Yashima.

Literary and pictorial accounts confirm that extensive planning and earthworks projects were utilized throughout the medieval era for major battles. For instance, the defense works at Ichinotani erected by the Taira clan in 1184 included boulders topped by thick logs, a double row of shields, and turrets with openings for shooting. Even if descriptions of such structures taken from accounts of the Gempei War dating to the late Kamakura era exaggerate these defenses, they capture the labor, time, and ingenuity involved in such efforts.

As wartime construction continued, Japanese military architects became skilled in adapting civilian structures that offered multiple options for warrior defenses. Composite barriers utilizing timber and other materials that protected crops from intruders and animals were helpful in subduing infantry offenses. Military architects familiar with agricultural irrigation principles constructed ditches and moats to deter mounted troops. In sum, military construction of the early medieval period involved tailoring familiar forms to warrior needs to provide an initial line of defense.

Some temporary construction types afforded flexibility and served well in both offensive and defensive situations. Kaidate (shield walls) and sakamogi (brush barricades; literally “stacked wood”) were both in common use by the 13th century. Kaidate, formed of rows of standing shields, had been employed since the end of the Asuka period (eighth century), and were valuable as portable field fortifications. Sakamogi, which were most likely inspired by barriers for livestock, were useful in several contexts as well. These deceptively simple structures continued to be effective in the age of gunpowder as they remained difficult to cross and also resisted explosive shells. Barriers made of shields could be made more effective through deployment atop, or in front of, another defensive form. However, as the power of the Ashikaga shoguns declined in the Northern and Southern Courts era, combat conditions changed, and samurai clans confronted elevated fortresses where warriors on horseback were ineffective.

Azuchi-Momoyama- and Edo-Period Castles

After the feudal system was reorganized by the Tokugawa shogunate, castles (shiro) were erected in the center of a daimyo’s domain, so they would be easily accessible. Without natural defenses such as hills and plateaus, these structures required additional protection compared with the elevated shiro built during the late Muromachi and Momoyama periods. For security, builders developed walls of enormous boulders that often had smooth surfaces that would be difficult to scale. Moats (hori) also provided a means to deter an attacking force.

The castle was not only a means of defense, but also served as the hub of administration and commerce in the domain. Castles housed the domain lord and chief retainers. Towns developed around the structures, called “towns beneath the castle” (jokamachi) since the castle was often elevated, and both literally and figuratively overshadowed all other buildings nearby. Merchants and artisans became an important aspect of life in these castle communities, as daimyo and their retainers had more time and disposable income than in the past. Further, the rise of fashion and interest in display (in the sense of decoration and adornment) that arose in the cosmopolitan Edo period made it necessary for members of the warrior class to keep up appearances, and this led to healthy economic growth even in provincial castle towns.

#

In the late Kamakura and early Muromachi eras, locally powerful landholders did not yet have the resources to commission and train considerable numbers of mounted warriors. At this stage, extensive forces designed for long-distance campaigns were unnecessary as well, since battles in the provinces often culminated in localized sieges to gain control of a strategically positioned castle. Thus significant numbers of well-trained foot soldiers were necessary to enter the territory of an opponent and scale his fortress. While swordsmanship began to gain prominence among samurai skills in the early medieval era, the primary warrior weapon among foot soldiers was a long polemounted arm called naginata, and this was supplemented by archery. Military drills using polearms involved learning to pull a cavalryman from his mount and engage him in close-range combat. Other practical applications of such weapons included thrusting, or throwing, a spear or other polearms in order to hit a distant target. Archers and infantry equipped with spears were also trained to send arrows over castle walls to cover the approach of foot soldiers who sought to scale the walls and thereby gain access to the castle.

#

Siege Warfare

Japanese castles were adapted to siege warfare. Again the similarities between Western and Eastern warfare are evident and the sophistication of Japanese siege-craft is obvious.

If a samurai is on the defending force, the following items are things he would be familiar with as he moved in and around the castle.

Arrow and Gun Ports

Inset into the walls of castle defenses are small holes—they are normally rectangular, circular or triangular. Positioned at different heights, the defenders use them to shoot out over the field of battle. However, shinobi creep up to these apertures and fire burning arrows and flash arrows through them into the interior of the castle grounds to discover details about the interior layout. In addition to this, they would throw in hand grenades to kill those shooting out at the opposition.

Stanchions, Walkways and Shields

Along the inside of castle walls, wooden stanchions and frames would support multiple levels of walkways—similar to modern day scaffolding. Samurai would use these levels from which to shoot outward, either through arrow and gun ports or over the tops of castle battlements from between shields. In addition to this, bridges that could be retracted were set up at various positions; if the enemy breached the defenses these walkways could be retracted, allowing defending samurai to kill the enemy from the opposite side.

Killing Zones

Walls, turrets and enclosures were created to form killing grounds and zones, where the defending army could attack the enemy with crossfire and pin them into a corner and halt movement.

Turrets and Palisades

As discussed before, the castles of the early Sengoku Period and before were generally smaller; walls could be protected by turret towers, wooden shields and semipermanent buildings that were made of wood and were built along the tops of walls. Shinobi had various mixtures that would set fire to these, fires that would be difficult to extinguish, helping to break through the castle defenses.

Allied Help

A defending castle could set up a series of fire beacons and send messenger relays to request allied forces to counter the siege. Sometimes the relieving force could surround the besiegers, forcing them to defend their own rear and fight on two fronts.

Sallies and Sorties

The castle would send out night raids and attacks when they thought that the time was right. They may even evacuate a castle from an non-besieged section—if any—through gates and ports. Shinobi were trained to watch the smoke rising from castles. If the smoke from cooking fires and kitchens was too much, too little, or later than normal, a shinobi would know that the enemy had either started to evacuate or that they were preparing extra food for those going on night raids or that the food stores were diminishing. All of which was information the shinobi would pass on to his commander.

Those who were attacking the castle had certain weapons and tools to help degrade the height and protection advantages of the defenders.

Trench Warfare

Trenches at their smallest were three feet deep with an earth mound on the top of around two feet; this total of five feet covered the average height of a samurai. The closer to the castle the trench lines were the deeper they had to be dug, as arrows could be shot into the defenses from such an angle.

Towers and Constructed Turrets

As discussed previously, the enemy battle camp had collapsible turrets and towers; these were erected to see enemy troop movements and shinobi.

Battering Rams

Covered rams on wheels were used to take down castle doors and break open sections of defenses.

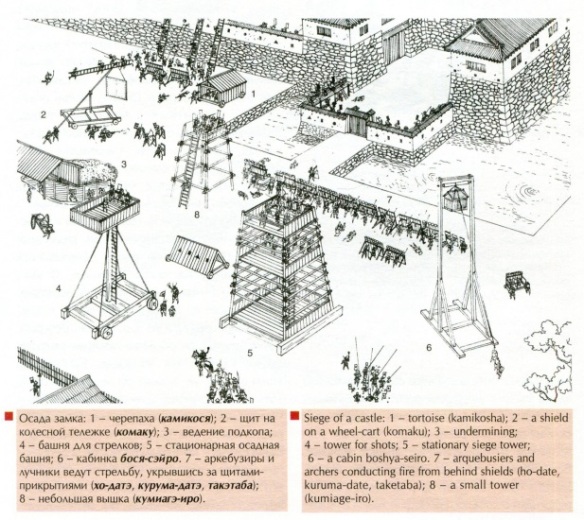

Shields and Walls on Wheels

Small platforms were placed on low carts with walls erected on the front. These walls had shooting ports and would be rolled into place, and from here attacking samurai could shoot at the enemy. This included walls mounted on arms that could be raised so that samurai could shoot out from below them and other such contraptions.

Shields, Bamboo Fences and Bundles

Human-sized wooden shields that stood erect with the help of a hinged single leg would protect samurai. In addition to this, bamboo was tied in large bundles and shooting ports were cut out of the middle. These bundles could be leaned against waist-height temporary fences so that samurai could shoot from behind cover.

Cannon and Fire

Cannon were used to launch fire and incendiary weapons and shot. Kajutsu—“the skills of fire”—included long-range rockets, flares and anything that causes flames in the enemy camp. Some shinobi were essentially agents who moved into the enemy castle and made sure that fires were set from within. One shinobi trick was to set a fire away from the main target to distract the defenders from the actual target and then to move on with their initial aim of setting fire to more important things like the main compound.

Tunneling

Tunneling was undertaken to undermine the enemy defenses. If done in secret and not on a war front, the tunnel had to start far from the target, or start from inside a nearby house. To discover if tunneling was taking place, empty barrels would be set into the ground to listen for mining below.

Moat Crossing Skills

Portable bridges and temporary structures were used to cross rivers and bridges. The shinobi’s task was to discover the length, width and depth of a moat and report the dimensions, or to cross it in secret at night.

On the whole, the samurai castle was a place of residence and the target of a siege. The samurai would defend and attack castles with ingenious tricks and tactics and shinobi on both sides would come and go, stealing information or setting fires to things, something that was quite normal in life as a samurai.