“Pacific Offensive, 1942: • Sergeant-Major, Infantry; Borneo, January 1942 • Superior Private, Infantry; Java, DEI, March 1942 • Seaman 2nd Class paratrooper, 1st (Yokosuka) Special Landing Unit; Celebes, DEI, January 1942”, Stephen Andrew

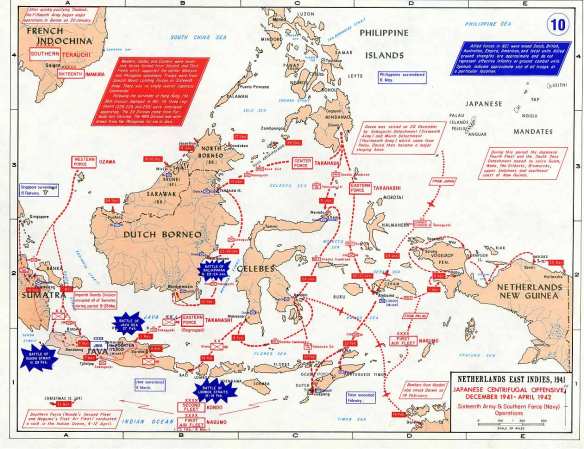

As the oilfields of Borneo – and two weeks later, the oil fields of Sumatra – would fulfill a strategic objective on the Japanese Southern Road, other moves made on the Dutch East Indies chessboard were designed to address tactical concerns. As the Japanese closed in on Java and Sumatra, the Dutch, who had barely defended Borneo, were concentrating their resources, just as General Arthur Ernest Percival intended to do with his British Commonwealth assets in Singapore.

Just as IJA and IJN airpower was keeping pace with Tomoyuki Yamashita’s 25th Army on the Malay Peninsula, moving into abandoned RAF bases closer and closer to the front, the tactical plan for the ultimate battle in the Dutch East Indies required a network of airfields on other islands which were closer to Java and Sumatra. One such island was the major Dutch East Indies island of Celebes (now Sulawesi) to the east of Borneo and due south of the Philippines.

Offshore, the Celebes operation was supported by a naval force commanded by Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka which included the cruiser Jintsu, his flagship, ten destroyers, two seaplane tenders, and several minesweepers. An additional covering force under Rear Admiral Takeo Takagi included the cruisers Nachi, Haguro, and Myoko, and two destroyers. They were all part of the growing IJN presence in the nearly 3 million square miles of Dutch East Indies waters.

The IJN surface fleet in this area was divided generally into two operating groups. The Western Force under Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, commander of the Japanese Southern Expeditionary Fleet, was tasked with operations in the South China Sea, and had supported the campaign in Malaya and Singapore. The Eastern Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Ibo Takahashi, conducted operations from eastern Borneo, east through Celebes, Ambon, Timor, and eastward to New Guinea.

Operations ashore in Celebes were conducted entirely by the IJN Special Naval Landing Forces, and occurred simultaneously with the IJA and IJN landings on Tarakan. This ground action, which was a brief one that history treats almost as a footnote to the Borneo operations, is notable for including the first Japanese airborne operation in Southeast Asia. The latter was a precursor to tactics that were to be revisited a month later in Sumatra.

Under the command of Captain Kunizo Mori, 2,500 men of the 1st and 2nd Sasebo Special Naval Landing Forces conducted the initial amphibious landings near the northern Celebes cities of Manado (also spelled Menado) and Kema before dawn on January 11, overwhelming the outnumbered KNIL defenders.

Meanwhile, staging out of Davao, 28 transport variants of the Mitsubishi G3M medium bomber carried more than 300 paratroopers from the 1st Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force to a drop zone behind the invasion beaches. Landing at about 9:30 am on January 11, the paratroopers surprised the Dutch defenders, and began an assault on the airfield at Langoan and the seaplane base at Kakas.

The unexpected attack from above certainly reminded the Dutch troops of the use by the Germans of airborne troops in the conquest of their home country in May 1940. Indeed, Japanese tactical planners in both the IJA and IJN had made note of the successful use of German Fallschirmjäger, or paratroopers, as a spearhead during the Wehrmacht spring offensive of 1940, and had begun training their own airborne troops. Germany’s capture of the entire island of Crete, solely by airborne troops, in May 1941, must have been especially noteworthy as the Japanese planners pondered the island-studded map of the Southern Road. In retrospect, it is a wonder that the tactic was not employed on a wider scale.

A second airborne attack by the 1st Yokosuka on January 12 brought additional landing forces to Celebes, and assured the capture of the Langoan airfield. Though some of the Dutch troops managed to hide out in the mountains for about a month, northern Celebes was secured by the middle of the month.

With this, Captain Kunzio Mori’s 1st and 2nd Sasebo headed south. Just as Sakaguchi had leapfrogged down the Borneo coast from Tarakan to Balikpapan, Mori embarked from Manado and headed for Kendari, at the southeast corner of Celebes. His Special Naval Landing Forces, aboard six transports, were escorted by a task force commanded by Rear Admiral Kyuji Kubo, which included the cruiser Nagara, his flagship, eight destroyers, and support ships. As with the task force that had supported Mori at Manado, Kubo’s contingent was part of the IJN Eastern Force.

Mori went ashore under cover of darkness on the night of January 23–24, the same night that Sakaguchi had landed at Balikpapan. Within 24 hours, the defenders had been overcome, and the Japanese were in control of the strategically important airfield at Kendari.

Capturing airfields was a priority second only to the petroleum facilities in the Dutch East Indies, for they brought land-based Japanese fighters and bombers incrementally closer to future battlefields farther south on the Southern Road. The air base at Kendari was destined to be one of the most important. Centrally located within the Dutch East Indies, it would be an important refueling stop. It was also the base of operations for the devastating air attack on Darwin, Australia, which would terrify the land down under three weeks later.

Just as the airfields on Celebes were part of the Sumatra and Java strategy, other Dutch islands far to the east hosted airfields that would be useful in operations against Dutch- and Australian-administered New Guinea, which were scheduled for April. Centrally located between Celebes and New Guinea was 299-square-mile Ambon Island, part of the Molucca (now Maluku) Archipelago, 500 miles east of Celebes, 1,600 miles east of Palembang, and 250 miles west of New Guinea. The strategic importance of Ambon and the substantial, paved airfield at Laha on the island had been lost on neither the Dutch nor the Australians. They had agreed to jointly reinforce the island, but the first contingent of RAAF Hudson bombers had not touched down at Laha until December 7, 1941, less than 24 hours before the general outbreak of hostilities across Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

The Australians also sent troops, but they had few to spare. As we have seen, three of the four infantry divisions which comprised the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were in North Africa helping the British fight the German Afrika Korps. Most of the 8th Division, except the 23rd Brigade, was helping the British defend Malaya.

The one brigade held back was given the precarious and impossible task of the forward defense of Australia itself. It was divided into what were known as the “Bird Forces,” having been given what the Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs historical factsheet colorfully describes as “ominously non-predatory names.” Forward defense of Australia meant outposts on islands north of that country and east of Malaya which were astride important sea lanes between Japanese-held territory and Australia. It was Gull Force that was dispatched to Ambon, while Sparrow Force went to Timor, and Lark Force went to New Britain, far to the east.

Each of the Bird Forces was essentially a single battalion, roughly a thousand or fewer infantrymen, reinforced with artillery and support troops. Deployed in 1941 before the full weight of the immense Japanese offensive had been experienced, each was sent to do a job that should have been done by a force a dozen times larger.

Deploying about ten days after Pearl Harbor, the 1,100-man Gull Force, centered on the 2/21st Battalion of the AIF, arrived on Ambon, joining a Dutch garrison on the island that consisted of the poorly trained 2,800-man KNIL Molucca Brigade, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Kapitz. Gull Force was initially commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Leonard Roach, but he was replaced on January 16 by Lieutenant Colonel John Scott, who was no stranger to amphibious operations, having participated in the Gallipoli campaign during World War I. Scott arrived to find his new command in pitiful condition, with malaria and other diseases rampant in the equatorial heat, which still swelters in January.

Both USN and Koninklijk Marine flying boats operated out of Ambon, flying patrol missions, as well as frequent evacuations of civilians, but they were pulled out in mid-January, against the backdrop of increasing Japanese air attacks. Air defense of Ambon consisted of a few Brewster Buffaloes, which rose to meet IJN seaplane bombers that began visiting Ambon early in January at the same time as the offensive against northern Borneo.

The Buffaloes held their own for a while, but they were no match for the carrier-based IJN Zeros that first appeared over the island on January 24, the same day as the invasions of Balikpapan and Kendari. For the Ambon operation, the IJN brought in the carriers Hiryu and Soryu, both of which had been part of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s Pearl Harbor strike force. At Ambon, they targeted Dutch and Australian aircraft, compelling Wavell to make the decision to pull out the last of the Allied aircraft to preserve them to fight another day. When the invasion fleet was sighted at dusk on January 30, the Allied ground troops knew they would have to face the enemy with no air cover.

The fact that the IJN had used seaplanes and carrier-based aircraft to conduct operations against Ambon is, in itself, an illustration of why the Japanese needed to have airfields at locations across the sprawling Indies.

The remainder of the naval escort for the ten transport ships of the invasion fleet to which the Hiryu and Soryu were attached was largely the same contingent that had supported operations against Manado on January 11. Commanded by Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, this force was comprised of his flagship, the cruiser Jintsu, as well as eight destroyers and support vessels. The same covering force under Rear Admiral Takeo Takagi that had supported Tanaka at Kendari also accompanied him to Ambon.

As in Borneo, the ground operation at Ambon was to be a joint operation between the IJA and the IJN Special Naval Landing Forces. The latter contingent included 820 men from the 1st Kure Special Naval Landing Force, while the IJA contingent of approximately 4,500 men was centered on the 228th Infantry Regiment, one of three regiments in the 38th Division, which had taken part in the conquest of Hong Kong. This joint force was known as the Ito Detachment and commanded by Major General Takeo Ito, who had commanded the entire 38th Division at Hong Kong, and who operated at Ambon under the banner of the division’s headquarters.

The first wave of IJA Ito Detachment came ashore during the night of January 30–31, with the IJN landing forces in the north, and the 288th mainly in the south. Ambon is nearly bisected by Ambon Bay, which cuts into the island from the southeast. The southern part contains the major population centers, while Laha airfield was across the bay on the northern part. Most of the defenders were located in these areas, but the initial Japanese landings were on the lightly defended north, and the least-defended area on the south side, well away from coastal guns guarding the entrance to Ambon Bay. Of course, established beachheads can be expanded more easily than landing troops under fire.

During January 31, the Japanese moved rapidly, reaching Australian-defended Laha from the north, and capturing Ambon City in the south by around 4:00 pm.

As the Allies shifted troops to face the landings, they left holes in their lines, which were exploited by the Japanese. A second wave of Ito Detachment troops came ashore at Passo (also written in some accounts as Paso) at the neck of the Laitimor Peninsula, effectively cutting the island in two. At the same time, the Japanese also snipped the telephone line which was the only way that the Allied troops could communicate with one another. The absence of communications isolated the various units and created confusion.

Kapitz ordered his men to continue fighting, which they did. However, shortly after midnight, the Japanese captured Kapitz, who had moved his headquarters close to Passo. For most of February 1, the action involved an Allied withdrawal, away from Passo and Ambon City, toward the southeast tip of the Laitimor Peninsula. These troops, with Colonel Scott still in command, had their backs to the Banda Sea, and realized that their position was essentially hopeless.

As this was ongoing, Admiral Tanaka ordered his minesweepers into Ambon Bay to clear the mines laid by the Koninklijke Marine, before they withdrew from Ambon earlier in January. This was in preparation for landing additional troops inside the bay. However, much to the immense joy of the troops fighting for their lives on the peninsula, one of the minesweepers struck a mine, blew up, and sank. Another was damaged.

Nevertheless, the jubilation that the Allied troops enjoyed at this juncture was certainly qualified by the pounding that was being dished out to them in the form of offshore naval gunfire and air attacks from the air wings aboard the Hiryu and Soryu. Throughout February 1, the naval bombardment also fell on the Australian and Dutch troops that were still trying to defend the airfield across the bay at Laha. On the morning of February 2, having encircled Laha, the landing troops, under Commander Kunito Hatakeyama, launched a ferocious assault aimed at dislodging the defenders. At around 10:00 am, Major Mark Newbury, commanding the joint force at Laha, decided that any further resistance would waste lives in an impossible situation, and ordered his men to surrender. Scott surrendered the defenders of the Laitimor Peninsula on February 3. About 30 Australian Diggers managed to successfully escape Ambon by canoe.

Newbury’s hopes of saving lives by his surrender were darkened when, over the ensuing two weeks, Hatakeyama randomly murdered around 300 prisoners at Laha. Newbury himself was killed on February 6. Scott survived the war as a POW, although most of the troops who surrendered on Ambon died in captivity. In 1946, witnesses and makeshift graves were located, and Hatakeyama was tried, convicted, and executed as a war criminal.