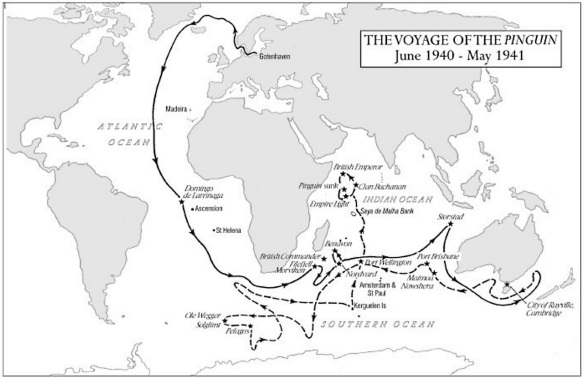

Krüder now had a choice of two routes in his attempt to break out into the North Atlantic. He could either take the shortest way out, passing between the Faeroes and Iceland or continue north to round Jan Mayen Island, and thence south-west through the Denmark Strait. The latter route would add something like 700 miles to the passage, but Krüder, unaware that the Faeroes Channel was temporarily unguarded following the sinking of the Andania by U-A, opted for the longer northerly route. He was also not aware that, as a direct result of the loss of the AMC, the Admiralty had ordered the cruisers Newcastle and Sussex to reinforce patrols in the Denmark Strait.

At 2300, when on the latitude of Trondheim, Krüder altered course to 320° to head for Jan Mayen. It was Midsummer’s Night, with no real darkness, and, perversely, the foul weather that had provided invaluable cover for the Pinguin since sailing now took a turn for the better. The wind dropped to a mere fresh breeze, the sea went down and the rain cleared away. The heavy overcast remained, but visibility improved dramatically. Then, early on the 23rd, the wind veered to the north-east and the sun broke through.

With no darkness to hide his ship Krüder felt dangerously exposed to his potential enemies, but he had little choice. The only course of action open to him was to make all possible speed for Jan Mayen and take cover in the fog banks normally found shrouding the island at this time of the year. Once hidden in the fog, he could then bide his time, waiting for suitable murky weather to cloak his breakout through the Denmark Strait.

Krüder was to be disappointed, for the weather beyond the Arctic Circle is as unpredictable as in any other part of the globe. As the day progressed and the Pinguin pushed north-westwards, although the wind was light and the sea a flat calm, the hoped-for fog did not materialize. The air was in fact crystal clear, so clear that at 0400 on the 24th, when it was fully light, the tip of the 7,500-ft Beerenberg, Jan Mayen’s volcanic peak, was visible at a distance of almost 100 miles.

Although Jan Mayen was said to be uninhabited, except for a Norwegian weather station, Krüder was reluctant to close the land, but he had no other alternative. Pinguin rounded the northern side of Jan Mayen at noon with all her guns’ crews stood-to and the ship in a state immediate readiness. The weather remained stubbornly fine and clear, but if the raider was seen from the shore she provoked no reaction. Once clear of the island, Krüder set course due west, running for the ice edge off the east coast of Greenland, where the warm summer air flowing over the frozen sea was guaranteed to bring dense fog.

To the great relief of all on board, not least her commander, the Pinguin ran into falling visibility when she was within 100 miles of the Greenland coast. By 1925 she was in thick fog and feeling her way towards the ice edge at slow speed. The ice was sighted just after 2100 and Krüder altered to run south-westwards, parallel to the coast and keeping just to seaward of the ice. Visibility in the fog had improved to around 500 yards, just sufficient for careful navigation, but it was a nerve-wracking business. There were icebergs about and, although the ship was down to a crawl, the danger of collision with one of these drifting monsters was very real, but this was a risk Krüder was prepared to take in the interests of a quick breakout into the Atlantic. For the moment he was grateful for the sanctuary of the fog.

Pinguin’s luck ran out on the morning of the 25th after she had steamed only 75 miles to the south-west. The fog suddenly thinned, then lifted altogether, giving way to the unseasonal clear weather experienced earlier. Krüder was now sorely tempted to make a dash for the Denmark Strait at full speed, but, with British cruisers in the offing, this could be suicidal. The weather forecasts he was receiving from SKL, based on reports sent in by German weather ships which lurked in these waters disguised as trawlers, indicated that conditions were likely to worsen over the next few days as a warm front moved up from the south. Krüder reversed course and steamed back into the fog to await the promised deterioration in the weather. Once hidden in this silent world of swirling mist, he informed SKL of his decision, using a special shorthand code devised for auxiliary cruisers. A ten-second burst of morse was sufficient to pass his message, a signal so brief that it had faded before any of the network of British W/T direction finding stations constantly monitoring the airwaves could home in on it.

The waiting was long and tedious, with the Pinguin, her engines idling, patrolling up and down off the ice edge, her crew largely unoccupied but unable to relax, for the hidden dangers in this fog-shrouded wilderness were many. It was a morale-sapping situation that Krüder had hoped not to meet this early in the voyage. He was very much relieved when, on the morning of the 28th, the barometer began to fall steeply and the wind picked up, sweeping away the fog. In its place came low, overhanging clouds laden with heavy rain. The warm front had arrived.

Running on one engine and making 9 knots, the Pinguin moved south again. The wind settled down in the east, rising to force 6 and building up an ugly beam sea that soon began to send freezing spray flying over the raider’s bridge. The skies came even lower, so that morning became night again, and it seemed that the Pinguin had drifted from one bad dream into another, this one far more malevolent. The sea was short and she rolled jerkily, adding to the misery of those on board. And then the ice came back. It began with isolated floes, which posed no danger to the ship, but soon growlers, and then full-sized bergs, came looming out of the murk. It was a nerve-jangling experience that lasted an agonising twenty-four hours. When the wind eased and visibility improved on the afternoon of the 29th Krüder was exhausted and greeted the clearance with immense relief, even though it did leave his ship exposed to detection by British ships, who might now be patrolling this area in strength.

Krüder need not have concerned himself, for the Royal Navy was elsewhere engaged. When France signed an armistice with the German invaders on 16 June, it immediately became clear that something must be done to avoid her substantial navy falling into enemy hands. The French ships, which included six battleships and two battlecruisers, were tied up in Oran, Dakar and Martinique, and were given the choice of surrendering to the Royal Navy or being sunk where they were. In order to provide the show of force necessary to back up this ultimatum, units of the Home Fleet were called in, leaving much of the North Atlantic, including the Denmark Strait, without adequate cover.

Pinguin emerged from the Denmark Strait on the morning of 1 July, having sighted nothing more threatening than a few isolated icebergs. She was now relatively safe, free to lose herself in the broad reaches of the North Atlantic. Her rendezvous with U-A off Dakar was planned for 18 July, which gave her time to spare. Krüder decided to put this to good use, steaming south along the meridian of 35° West at reduced speed, thereby conserving fuel, and at the same time being on the lookout for any unescorted Allied merchantmen taking the northern route between Canada and Britain. His luck was not good, for in five days he sighted only one ship, and this turned out to be the British armed merchant cruiser HMS Carmania. Believing the Carmania to be faster and more heavily armed than the Pinguin, Krüder turned away and ran. There was no reaction from the other ship, which seemed not to have sighted the raider.

By midday on the 7th the Pinguin was approaching the USA–UK convoy route and it was necessary to proceed with extreme caution. Over the next two days clusters of masts and funnels were seen on the horizon from time to time and evasive action was taken. The weather was fine, with excellent visibility, and, in spite of the Pinguin’s low silhouette, there was always the risk that an inquisitive convoy escort might sight her and come racing over the horizon. The appearance of a Russian ship in these waters would certainly arouse suspicion and could easily result in a gun fight Pinguin might lose. Another disguise was needed, and on the 10th, in fine warm weather, all hands turned to with paint brushes and the Petschura’s bogus voyage ended as it had begun. By nightfall Pinguin had taken on the identity of the Greek cargo vessel Kassos.

As the Pinguin sailed on southwards to her rendezvous with the U-boat, 5000 miles away in the Indian Ocean an encounter took place which would have a profound effect on the war at sea.

On the morning of 11 July the 7506-ton British ship City of Bagdad, outward bound from the UK with a full cargo for Penang, was approaching Sumatra and nearing the end of her long voyage. At 0730 she sighted what appeared to be another British cargo vessel on her starboard beam. There was nothing unusual about this; she was near one of the crossroads of the Indian Ocean frequented by British merchantmen. Then, suddenly, the other ship went hard over and headed straight for the City of Bagdad. She passed close astern and then came round to run on a parallel course, keeping about 1½ miles off. A flag signal fluttered from her yards, but this was unreadable from the British ship, despite the close proximity. However, the suspicions of Captain Armstrong White, master of the City of Bagdad, were already aroused. He ordered his wireless operator to transmit the ‘QQQQ’ signal, indicating that they were being attacked by a disguised enemy merchant ship.

The ‘enemy merchant ship’ was in fact the Atlantis, ex-Goldenfels, sister-ship to the Pinguin, which had sailed from Germany in March under the command of Kapitän-zur-See Bernhard Rogge and had already caused considerable disruption to Allied shipping in the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean.

The Atlantis ran up her shutters and opened fire as soon as the first urgent notes of the City of Bagdad’s transmission were heard. The raider’s guns pounded the British ship with salvo after salvo of 6-inch shells, until she was stopped and on fire with three of her crew lying dead and two others injured. A boarding party from the Atlantis then sank her with explosive charges.

The City of Bagdad might have been just another victim for the Atlantis to add to her mounting score but for one important omission by the British ship’s crew. In the confusion of the attack they failed to dump overboard the vital BAMS (Broadcasting for Allied Merchant Ships) code books. These were seized by the boarding party and sent back to Germany via Japan at the first possible opportunity. Within weeks Berlin was reading all coded signals to and from Allied merchant ships. It was some months before the Admiralty became aware that their ciphers had been compromised.

On 12 July, at the request of SKL, the Pinguin broke radio silence to report her position. She was then 700 miles north-west of the Cape Verde Islands, having been continuously at sea for almost three months. SKL’s reply contained the latitude and longitude of the proposed meeting with U-A on the 18th.

The rendezvous position was reached at noon on the 17th. It was a lonely spot midway between Africa and the West Indies and well away from the shipping lanes. Krüder stopped his ship and waited, growing increasingly anxious as the hours dragged by, for, although the Pinguin was in an empty ocean, there was always the risk that a British warship might appear on the horizon. He heaved a sigh of relief when, at first light on the 18th, a long, low grey shape materialized out of the morning mist. U-A was on time.

Unfortunately, the U-boat brought with her an unwelcome change in the weather. A fresh NE’ly wind blew up, raising a choppy sea that made it impossible for the transfer of supplies to take place. Krüder decided to head south in search of calmer waters, on the way passing 70 tons of diesel oil to the submarine, so that she would have sufficient fuel to reach Biscay should it not be possible to store her.

On the 20th the two ships reached a position 720 miles southwest of the Cape Verde Islands, where the sea was calm enough to bring U-A alongside the Pinguin. This was the first time ever that a U-boat had been stored at sea by a raider and the inevitable problems arose. It was soon discovered that the submarine’s hydroplanes prevented her from coming close alongside and most of one day was lost in rigging sheer legs to bridge the gap. The torpedoes, eleven in all, were ferried across using flotation bags. It was a slow operation, and it was not until the afternoon of the 25th that the transfer was completed.

The Pinguin then took U-A in tow and set course to the southeast to meet up with the track followed by Allied ships between South American ports and Freetown. Once on this line, U-A had orders to make for the approaches to Freetown and there lie in wait for ships entering and leaving the harbour. Freetown was the assembly point for UK convoys, so Cohausz anticipated he would find more than sufficient targets for his newly-acquired torpedoes.

The opportunity for action presented itself sooner than expected. At 2300 on the 25th the lights of a ship were sighted to port and on a converging course, and U-A at once cast off to investigate. Krüder, being only an interested spectator at this stage, held the Pinguin back in the dark to await developments.

After about an hour had passed, Cohausz returned to report failure. He had identified the ship as an Allied tanker, an easy enough target, but his first torpedo had been a ‘rogue’. It ran in circles before turning back to home in on the U-boat that fired it and Cohausz was forced to take violent evasive action to avoid being sunk by his own torpedo. By the time he regained control, the tanker had disappeared into the night, probably not even aware of its brush with disaster.

U-A was taken in tow again, but a heavy swell developed the next day and the towrope snapped. From then on the U-boat proceeded under her own power with the Pinguin keeping company. Cohausz took his leave at noon on the 28th when they were 850 miles to the west of Freetown. The raider, her supply and escort duties at an end, was now free to begin her own war.