The morning of the 21st dawned, still stormy. The bulk of the Royal Navy fleet was anchored about three miles from Dumet Island at the mouth of the Vilaine river. To his astonishment, Hawke saw the Soleil Royal anchored nearby and only eight other French vessels in sight, beyond and inshore of the British line. Finally understanding his desperate position, Conflans slipped anchor and tried to reach Croisic Roads where there were protecting batteries. Hawke sent the Essex in pursuit but both she and her quarry ran aground on Four shoal, hard by the Héros, similarly disabled. This was now a veritable graveyard of ships, for at 10 p.m. the night before the Resolution had also struck a reef here and run aground. Hawke meanwhile weighed anchor and gave the signal to attack the other French ships in the Vilaine. But it was blowing so hard from the north-west that he finally considered the attempt suicidal and struck topgallant masts. With the aid of the storm and a favourable wind, the French vessels managed to cross the bar into the Vilaine river – a feat they could probably not have achieved in any other weather conditions; as it was, they had to jettison all guns and gear to get to safety. The conjuncture of the tides and the freak high-water level in Quiberon Bay combined to provide a unique, unrepeatable opportunity.

All that day the gale raged ferociously and unceasingly. Not until evening did Hawke dare even to lower boats to rescue the crew of the stricken Essex. It was only on the 22nd that Hawke sent in three ships to finish off the Soleil Royal and the Héros. Seeing the British about to descend on him, Conflans set fire to his flagship and escaped; he did not even tarry to save the magnificent artillery on board. The British arrived and boarded the blazing flagship but had no time to do more than carry off the golden-rayed figurehead. Duff’s men then completed the French discomfiture by burning the Héros. Hawke worked up as far as the Vilaine estuary and even found an anchorage, but concluded there was no way he could reach the other French ships. Duff and his captains reconnoitred the lower reaches of the Vilaine in small boats and at first there was some hope that they could send in fireships, but this later proved chimerical. The French ships were now, at any rate, out of the war, though some did return to service a year later. Hawke now proceeded to tighten his hold on the Brittany coast. He sent Keppel with a flying squadron to investigate French ships said to have taken refuge in the Basque Roads, but these vessels proceeded up the River Charentin, out of reach of the Royal Navy, so Keppel returned to Quiberon Bay. And he seized Belle-Île, a wonderful base for raids on France’s west coast.

In the euphoria of victory Hawke did not observe the precise rules of warfare as understood by eighteenth-century international law, and this embroiled him in an acrimonious and abrasive correspondence with d’Aiguillon. Although he sent the French wounded ashore, he reserved the right to extract the big guns from the Soleil Royal and set about their removal. D’Aiguillon and his second-in-command, the Marquis de Broc, protested that the Soleil Royal and the Héros had never struck, so that Hawke could not claim them and all their contents as lawful prizes of war. When Hawke disregarded the protests, d’Aiguillon ordered local militiamen to open fire on any British working parties attempting to remove artillery from the Soleil Royal. Matters quickly escalated: Hawke opened fire on Croisic and threatened a systematic bombardment if his men were attacked again. He then seized the Île d’Yeu, halfway down the coast to Rochefort, destroyed its defences, rounded up all the cattle there and slaughtered them to feed his hungry sailors. At the end of the year Hawke returned in triumph to England, handing over the continuing blockade of Quiberon to Boscawen.

Quiberon Bay was one of the great naval victories in world history. It may lack the totality of Nelson’s later triumphs at the Nile and Trafalgar, if only because many of the French ships never got into the fight; and it was not a decisive event in the sense that Salamis, Actium and Tsushima were. It did not even have the obvious drama of Lepanto. But a sea battle fought in a violent storm will surely remain a unique event in all the chronicles of the ages. Hawke never really got the praise he deserved and there is even something defensive in the way he described the battle to the Admiralty:

In attacking a flying enemy, it was impossible in the space of a short winter’s day that all our ships should be able to get into action or all those of the enemy brought to it . . . When I consider the season of the year, the hard gales on the day of the action, and the coast they were on, I can boldly affirm that all that could possibly be done has been done. As to the loss we have sustained, let it be placed to the account of the necessity I was under of running all risks to break this strong force of the enemy. Had we but two hours more daylight, the whole had been totally destroyed or taken; for wewere almost up with their van when night overtook us.

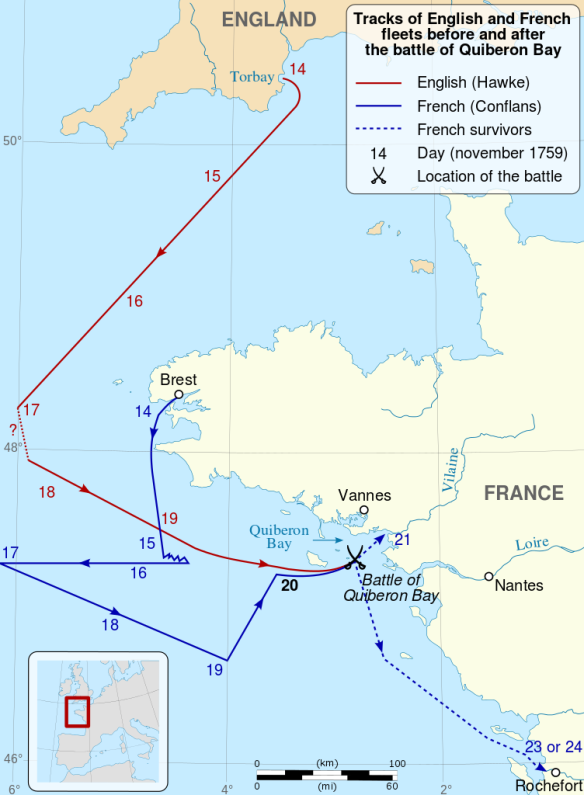

At Quiberon, Hawke lost two ships and 300–400 men. The French lost five, including their flagships Soleil Royal and Formidable, and more than 2,500 men, most of them drowned. Additionally, four of the seven vessels that had taken refuge in the Vilaine ended up with their backs broken. Essentially Hawke’s victory was the result of superior seamanship and his readiness to risk all to defeat the enemy. His was a stunning achievement in such weather. Ungenerous critics say that Hawke was above all lucky in meeting the victuallers when he did near Ushant, while Conflans lost three days to gales. But against this counterfactual can be set another, which says that if Hawke had not arrived at Quiberon Bay until 22 November, he would have entered the bay and won an even more spectacular victory while Conflans was trying to embark d’Aiguillon’s invading force. Certainly Hawke always attracted contrary opinions. At the very moment of his victory, the British mob, frustrated with the lack of a decisive breakthrough, was burning him in effigy. When news of the victory reached London it was of course a different story. Horace Walpole wrote to his confidant Mann: ‘You would not know your country again. You left it a private little island, living upon its means. You would find it the capital of the world. St James’s Street crowded with Nabobs and American chiefs, and Mr Pitt attended on his Sabine farm by Eastern monarchs, waiting till the gout has gone out of his foot for an audience.’ For all that, Hawke himself was ill requited. He was awarded a £2,000-a-year pension, but nothing else. Since Pitt did not like him and Anson was jealous of him, he waited in vain for further recognition for his triumph at Quiberon. After Finisterre in 1747 he had been raised to the peerage, but the ruling elite, still full of Wolfe-mania, ignored a far greater hero.

But for Conflans and the French, Quiberon was an utter catastrophe. The general opinion in France was that Conflans deserved to live in eternal infamy for the events of 20 November 1759. Opinion in the streets of Paris was inflamed, but not more so than in Brittany, where the people turned violently against the whole idea of foreign invasions; in Vannes the locals tore down theatre posters and would not allow the actors of the Comédie Française to perform for d’Aiguillon and his officers. Conflans lamely told Berryer that he had done his best and acted with ‘firmness and wisdom’. The problem, in his view, was the quixotic attempt to mount an invasion in winter. To d’Aiguillon the day after the battle he was blunter: ‘What can we do with such marked naval inferiority? At least this debacle should put an end to these ill-coordinated land and sea combined operations.’ He left the navy soon afterwards and died, forgotten, in 1777. Conflans was a mediocre by-the-book admiral who did not seriously confront his own errors. Obsessed with avoiding a battle at all costs, he was indecisive for the whole of 20 November. First he headed towards the enemy, then he fled in such haste as to leave his rear unprotected. Once at Quiberon he dithered again: first he wanted to get inside the bay, and then he wanted to get out. As the true hero of the day on the French side, Saint-André du Verger remarked: ‘The circumstances of this day’s work are a disgrace to our Navy, and show only too well that it has but a handful of officers with initiative, courage and skill; that nothing else will do but to reorganise the service from top to bottom, and to provide it with commanders who are capable of commanding.’

Yet the real villain of 20 November was Bauffremont, who disobeyed standing orders and also the particular command from Conflans that he should never lose sight of the flagship. He was later accused of having deliberately ignored signals from Conflans out of jealousy and personal dislike; the fact that he was aided and abetted by Bigot de Morogues, still smarting after Conflans went above his head to Choiseul, adds circumstantial colour to the charge. That Bauffremont acted like a coward or a dullard seems scarcely disputable; the only serious argument is about whether he was guilty of treason or just terminally stupid. Bauffremont’s protestation that he acted on his pilot’s advice is irrelevant, if that meant ignoring explicit orders. But he soon added bluster to his other blemishes and indignantly wrote to Berryer to know why he was being cross-questioned. When Berryer on i December ordered him and all the ships at Rochefort to clear at once for Brest, Bauffremont sulkily replied that it was impossible, yet he would try to perform the miracle requested. On 21 December he sent a long screed of apologia to Berryer. Surely his action in sailing for Rochefort, thus saving eight ships, was better than staying with Conflans, where these vessels would either have been gutted or bottled up, useless, on the Vilaine? He then got on his high horse and declared that he should by now have had Berryer’s express commendation for what he had done. Bauffremont remained completely unapologetic and, in a bellicose letter to Choiseul in 1762, demanded to know why he was being held responsible for the disaster at Quiberon when French commanders genuinely responsible for debacles like Crefeld and Minden were never censured. The Ministry of Marine formed its own opinion on Bauffremont and made him wait until 1764 for the Lieutenant-Generalship he solicited two years earlier.

The contrast between the mild treatment of Conflans and Bauffremont by France and the savagery meted out by England to Admiral Byng in 1757 is clear. One shudders to think of the likely treatment of Bauffremont by the Admiralty. His self-defence (all the later blustering aside) was essentially twofold: he always obeyed orders but did not see Conflans’s signals; and he exercised the sort of discretion that he imagined his leader was even then exercising. But Bauffremont really could not have it both ways. If he was not in command, then he had to obey Conflans’s orders; the transparent fiction that he did not see the Marshal’s signals fooled nobody, and he was anyway under a strict professional obligation not to lose sight of the Soleil Royal. He also overlooked his clear duty as chief of squadron -which was to inform all ships in his division of his decision to run for Rochefort. He could not therefore logically state that other captains took the sauve qui peut decision to run for Rochefort independently, but he did so because it was one of the main planks of his defence. Bauffremont therefore stands convicted on a number of moral counts. He neglected his duty both to his superior and his subordinates and sinned against discipline and against the honour of the French Marine. Like other captains guilty of dereliction of duty he forgot the cardinal rule: all initiatives must not be independent but within the context of the Commander-in-Chief’s general orders. By trying to exculpate himself with a number of different arguments, Bauffremont simply impaled himself with self-contradiction.

Bauffremont probably escaped court martial only because Berryer had more important things on his mind. On 25 November he informed d’Aiguillon that the expedition to Scotland was officially suspended. The troops at Morbihan, almost atrophied from months of inaction, were given furlough. However, because of the continued presence of the British on the Atlantic coast, d’Aiguillon’s army was not disbanded and transferred to service in Germany, but broken up, cantoned, dispersed along the coast and used to repel invaders in Brittany and Gascony. The Basque roads and Belle-Île were now being used as anchorages by the Royal Navy who were so confident of quasi-permanent occupation that they used several islets as extended vegetable gardens. The mighty French fleet had been humiliated and, like the German Grand Fleet after Jutland, never put to sea again during the Seven Years War. Although naval captains and Jacobites continued to lobby Versailles to attempt an invasion of Britain with unescorted transports, the ministers had gone sour on ‘descents’. The debacle at Quiberon played into the hands of those members of the Council of State who wished to concentrate on continental warfare, and even Berryer’s prime interest in the ships that had got away to Rochefort was to disarm them so that he could save money.

For Pitt, Quiberon was the victory that set the seal on the year of victories. 1759 had been like a dream for him. He had made the Royal Navy the pivot of his global strategy and had been successful beyond anything he could have imagined. Seapower had enabled him to win the struggle for the West Indies, to defeat France in the battle for mastery in North America and to devastate all Choiseul’s counter-offensives. With Anson and Hawke, a talented team, he had successfully introduced the innovation of a fleet-in-being, for no armada like Hawke’s had ever been at sea for so long, or would be again for forty years. Britain was now incontestably a great power – perhaps the greatest of all time at this moment – and controlled the world’s sea lanes: to North America, to the Caribbean and to the Orient. Pitt’s triumph gave new heart to Frederick of Prussia, currently at the nadir of his fortunes. By diplomatic finesse had kept Spain out of the war, though Pitt knew that Spain was still fearful that Britain was now all-powerful in all theatres, and that ill-considered schemes, such as Newcastle’s ambition to control the Baltic by seapower, were likely to alienate her and make new enemies. Even so, Anson was able to announce that in 1760 the Royal Navy would have an unprecedented strength of 301 ships and 85,000 sailors. But most of all, Quiberon destroyed for ever any lingering hopes of a Jacobite restoration. Bonnie Prince Charlie might sulk in his lair at Bouillon, like Achilles in his tent, but no deputation of despairing French Achaeans would ever visit him to beg him to re-enter the fray.