There was good news from other theatres. Although Rodney’s attack on flat-bottoms in September had to be called off because of high seas, which threatened to smash his ships onto the coast, the endeavour confirmed his opinion that flat-bottoms could operate only on a millpond sea, and as autumn wore on there would be fewer and fewer of those. Then, at the end of September, Commodore Hervey directed a daring boat attack close to the entry of Brest harbour, engaged four ships in Camaret Bay and captured a schooner. The blockade was hurting the French badly, as they later admitted. Even at the simplest level, their matelots were cooped up in inaction and inertia while constant vigilance meanwhile kept Royal Navy crews at a high pitch of readiness.

One of the crosses Hawke had to bear was that the Admiralty constantly nagged him and tried to micro-manage his blockade, forcing him to pile up a mountain of paperwork in which he justified his every action. The Lords of the Admiralty put a negative ‘spin’ on Hawke’s demands by giving out that he required a superiority in capital ships before he would take decisive action against the French. Anson and Hawke were particularly at odds over the putative threat from Bompart’s West Indies squadron. Hawke’s only concern was that this might try to reinforce Conflans at Brest, possibly catching the Royal Navy between two fires, but he felt confident enough to intercept Bompart if he made for Rochefort without breaking stride on the blockade of France’s northwest coast. Anson, though, was adamant that Hawke had to have local superiority at Brest, and instructed him (with some asperity) that if Bompart did not interfere with the blockade and headed straight for Rochefort, Hawke should ignore him. Reluctantly accepting these orders, but hoping to make a virtue of necessity, Hawke decided to forget about Rochefort altogether and transferred Geary’s squadron there to the Brest theatre, to reinforce his local superiority. In Hawke’s opinion, the entire Admiralty brouhaha about Bompart was a storm in a teacup since, to move from the metaphorical to the actual realm, the hurricane season in the Caribbean (August–September) meant it was extremely unlikely that Bompart would soon sail for France anyway.

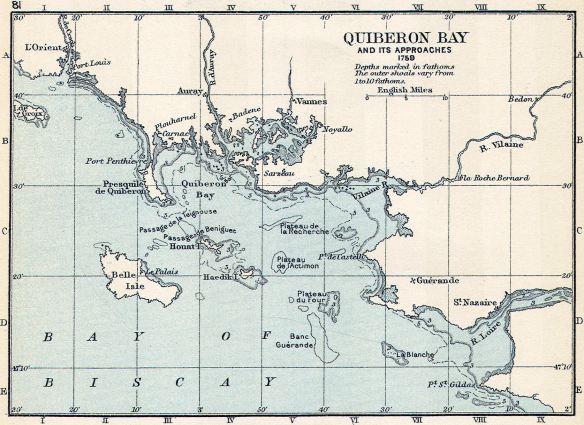

October saw the pace of French preparations quickening, especially when the Due d’Aiguillon arrived at his command headquarters at the Jesuit seminary in Vannes. Conflans had a golden opportunity to clear from Brest in mid-October when ferocious storms battered the Royal Navy. Reynolds, on surveillance at Île de Croix, was forced to rejoin Duff at Quiberon Bay when heavy gales blowing continuously from 11 to 14 October obliged his ships to strike topgallant masts. The united force contemplated an attack on the transports in the River Auray as a way to turn the storms to immediate advantage, but a council of war on the Rochester on 15 October concluded that an attack on the Morbihan transports was far too dangerous, especially as the Achilles struck a rock and was nearly wrecked; treacherous or venal pilots were blamed for the mishap. Off Ushant, Hervey was buffeted by heavy gales from the south-west, which swept in on a long heavy swell. Forced back to the Lizard peninsula, he was however able to return to Ushant when the weather moderated and to report that there was still nothing stirring at Brest. Hawke, aware that his men were weary after six months’ cruising in unpleasant waters, raised the blockade of Brest and returned to Plymouth, where he took the opportunity to lay in a three-month supply of fresh water. Normally the onset of winter meant an end to naval campaigning, and Hawke might have been confident that Conflans would not put to sea in such weather. But these were not normal times and nothing could be taken for granted.

Ominously, when Boys was driven off station at Dunkirk by a violent gale on 15 October, Thurot took the opportunity to escape with five frigates and 1,100 men. It was perhaps fortunate for Britain that he was detained by bad weather in Gothenburg and then again at Bergen.

Since for five days (15–20 October) there were no significant forces investing the French Atlantic ports, why did Conflans not put to sea, pick up the transports and proceed to Scotland, especially as he had just received a direct order from Louis XV to counterattack the blockade at Brest and Morbihan? Conflans, though, was no seafaring buccaneer in the Nelson or John Paul Jones mould, but a by-the-book plodding precisian. He was still bombarding the Ministry of Marine with requisitions, refusing to put to sea until he was completely crewed and victualled. He pointed out that provisioning was a particular problem, since storeships destined for Brest had been driven by the Royal Navy into Quimper and the victuals then had to be unloaded and trundled for 100 miles over very bad roads to Brest. On 7 November Conflans wrote a letter to Berryer that positively drips with sarcasm: ‘I see neither money nor ship’s timber nor workers nor provisions. I am sure you made arrangements to deal with all these contingencies.’ To an extent one can sympathise with him. The horse transports had been rotting away in the roads for the past three years and the battleships were not ready for action, except for the occasional star like the eighty-cannon Soleil Royal – state-of-the art warship and pride of the French navy. But Conflans was not just short of supplies and stores. Manpower was an even bigger headache, with Captain Guébriant of the Orient complaining that he had only thirty good seamen in his entire ship. It was all very well to press raw recruits, but they were incompetent at carrying out the complex battle manoeuvres necessary in any meaningful engagement with Hawke. Whatever the excellence of Conflans’s reasons for delay, the King and the ministers at Versailles were tearing their hair out. Infuriated with Conflans, Choiseul tried to encourage d’Aiguillon by mendaciously assuring him in October that Sweden was secretly with France and was only waiting for the French landing in Scotland to show its hand and declare war on Britain.

The weather ‘window’ passed, and on 20 October Hawke resumed his station off Brest. His confidence was rising daily, especially when he learned that Conflans’s ships were still nowhere near ready to come out, as all their topmasts and topgallants were still down. He also heard from Duff that, although there were now five regiments at Auray and eight at Vannes, all sixty vessels there had their sails unbent. Hawke had recently received reinforcements from Boscawen’s fleet, and was particularly pleased to be joined by Captain Sir John Bentley, a veteran of both battles of Finisterre in 1747, a fleet captain in the Royal Navy, and recently knighted for his sterling performance at Lagos. The only irritant was that the Admiralty had now changed its mind on the Bompart squadron. It turned out that after all they did want Hawke to intercept it, so he suggested sending Geary back to Rochefort to do the job. Confident that his advice would be accepted Hawke sent Geary on his way, only to be forced to recall him when the Admiralty lords, possibly heeding Bocsawen, who thought Geary was an idiot (‘a stupid fellow’), ordered Hawke to do so and suggested that he was not keeping the principal objectives (the blockades of Brest and Morbihan) clearly enough in the forefront of his mind. Hawke might have been justified in asking the noble lords whether the information about Bompart was meant to be taken at some metaphysical level only.

From the beginning of November it was the wind and waves rather than the tactical acumen of the rival naval commanders that determined the progress of the campaign. The volatility of the weather can be tracked in wind direction and velocity: westerly at the end of October, the wind then blew from the south-south-east on 1–2 November, from the south-southwest on the 3rd, from the south-west on the 4th and from the north-northwest on the 5th, when it began blowing a full gale. By this time Conflans was being deluged with urgent messages from Versailles, and Choiseul especially, demanding that at least the d’Aiguillon part of the invasion should be attempted, with Conflans picking up the transports at Morbihan before clearing for Scotland via the west coast of Ireland. Having evaded Hawke, Conflans was to blast passage through Duff’s blockading squadron off Morbihan; if a general engagement became necessary, Louis XV would accept the risk. The Admiralty’s spies intercepted Choiseul’s latest letter and the order went out from Anson that all ships should converge at Brest for a general engagement. These orders reached Hawke on 5 November, just as the sea began making up alarmingly. On the very same day Conflans wrote to Minister of Marine Berryer that he was determined not to abort the invasion project but would try to avoid a general engagement at sea. Naturally, if caught he would fight hard and acquit himself well, but the evasion of Hawke by stealth remained the prime objective. Conflans’s critics allege that this determination to avoid battle finally became an obsession, with disastrous results.

The bitter westerly gale of the 5th became a ferocious storm by the night of 6–7 November. Hawke’s fleet was battered mercilessly by heavy squalls of wind and rain as it tried unsuccessfully to work to the westward. As the wind backed gradually from northerly to westerly, the damage to the ships increased inexorably, with split sails and damaged masts. Topgallant yards were got down and topsails close-reefed, but the heavy western swell bore the armada increasingly off station. On the morning of the 7th Hawke reluctantly gave up the unequal struggle and bore away for Torbay. Duff and the cruisers were left to watch Brest and to send a frigate to Torbay if Conflans sortied. Later the very same day the winds of storm that had sent Hawke back to England brought Bompart’s squadron from the West Indies into Brest. Here was serendipity. Not only did Bompart learn from an unimpeachable source that Hawke’s fleet was no longer blockading, but Conflans’s crewing problems were solved at a stroke: although Bompart’s vessels were no longer battle-worthy, he simply transferred the seasoned crews and the supplies and matériel to his own battle fleet. But the French wrongly concluded that Hawke had returned to England for the winter. Had the Duke of Newcastle had his way, this would indeed have been the outcome. Afraid that the fleet would sustain severe damage if it had to struggle further with the winter storms, Newcastle strongly counselled the path of discretion. But, after some warm exchanges of opinion, Pitt, adamant that Hawke must put to sea again, had his way.

In Torbay, Hawke chafed in inactivity and frustration. Although a period of rest and recuperation was necessary for the storm-tossed ships, many of which had suffered badly split sails, Hawke worried that this lull might play straight into Conflans’s hands. But the hard gales of 10–11 November meant that getting out to sea was not possible. On the 12th the wind moderated, and Hawke momentarily hoped he could return to station. He cleared with nineteen men-of-war and two frigates, but he was barely into the Channel before the wind speed and wave height increased steeply. Faced with a south-west gale and a heavy swell, and with the warships again suffering split sails while not even out of sight of land, Hawke hung on grimly until the morning of the 13th when the savage state of the foam-flecked seas forced him to return to Torbay. At least there was some consolation, for Admiral Saunders and the Quebec fleet arrived back in England after a perilous Atlantic crossing. After his heroic work on the St Lawrence, Saunders would have been justified in taking leave, but he immediately volunteered himself and his ships for Hawke’s service. The British Quebec fleet for the French West Indian one, Saunders for Bompart: truly all paths now seemed to be leading to Quiberon Bay. There was a general sense of anticipation in the air as Anson rushed additional workmen to Portsmouth and Plymouth to get every available warship ready for seagoing.

It was not until 14 November that the storms abated sufficiently to allow the first of Hawke’s fleet to put to sea; many did not get away until the 19th. He was supremely confident in his own abilities and those of his sailors, whose morale, diet and health he had worked on so assiduously. Perhaps his only worry was that he had not been able to achieve a systematic charting of the French coast, so that he did not have an accurate picture of the reefs, shoals, fathom soundings, tides, anchorage grounds and batteries in all the Atlantic locations. Even as he toiled down the Channel towards Ushant on the 16th, Hawke met four victualling boats, whose captains informed him that Conflans had emerged from Brest on the 14th and the day before had been just sixty miles from Belle-Île, the large island off the coast of the Quiberon peninsula. Since it was obvious that the Admiral-Marshal was heading for Morbihan, Hawke sent fast cutters to all his captains to alert them that the prey was afoot. He wrote to the Admiralty: ‘I have carried a press of sail all night with a hard gale at S.S.W. and make no doubt of coming up with them at sea or in Quiberon Bay.’ The timorous Duke of Newcastle, who earlier glumly concluded that nothing could now prevent a French invasion – though he thought it was aimed at Ireland – wrote ecstatically to the Duke of Bedford: ‘It is thought almost impossible that M. Conflans should escape from Sir Edward Hawke . . . As to fighting him, which is given out by the French, my lord Anson treats that as the idlest of notions.’

Once he cleared from Brest, Conflans stood away to Morbihan on a north-west breeze; he was just over 100 miles from his destination and had a 200-mile lead over Hawke. In his fleet were twenty-one ships of the line in three divisions, under Budes de Guébriant, St André du Verger and the Chevalier de Bauffremont; but, fatally, there were just five cruisers to watch for enemy movements. By midday on 16 November Conflans was halfway from his target, about sixty-nine miles west of Belle-Île. But that afternoon the wind blew in fiercely from the east and built up into a gale, with heavy, breaking seas. Forced to run before the wind, and unable to stop until they were 120 miles west of Belle-Île, the French in effect lost three days to the storm, being exactly in the same position three days later. It was only on the 18th that Conflans could start reaching back, and even then not on a true course. The wind had settled in the north-north-east, which meant that to make easting he had to stand away far to the south. When the breeze died away on the afternoon of the 19th, he found himself becalmed about seventy miles south-west of Belle-Île. Incredibly, he was no nearer his destination than when he had been spotted by the British victualling ships on the 15th. Conflans has been bitterly criticised for his tardy performance but, although his crews may not have been as skilful as Hawke’s, the adverse weather explains most of the delay. Some poor seamanship there may have been, but Hawke did not clock up a much better mileage with a superior fleet.

It was not until nearly midnight that the wind sprang up again, now blowing from the west-north-west. From having been becalmed, Conflans was soon once again exposed to the fury of a gale. The seas were so high that he dared not approach close to land, even though he had issued orders late on the 19th to prepare for landing at Morbihan the next day. He signalled to his ships to proceed under short canvas, to ensure they did not reach land before dawn.

Compelled to reef all sails to prevent his being driven onto the shore, Conflans lolled perilously on the waves, hove to about twenty-one miles west of Belle-Île and there, at daybreak, Duff’s five-ship patrol spotted them. The French had no difficulty in chasing off the patrol, but now the secret of their position was out. Fortune meanwhile had smiled on Hawke. At first the winds drove his fleet westward, but on 18–19 November, though variable, they were more favourable, so Hawke followed a south-easterly track. By now he was running parallel with Conflans on a north-north-east wind and got to within seventy miles of Belle-Île before the following wind ceased. By noon on the 19th he found himself beset by heavy squalls from the south-east, west by north of the island, flying double-reefed topsails. The gale that hit Conflans at midnight reached Hawke five hours earlier, so that at 7 p.m. he signalled the fleet to send up topgallant masts, shake out reefs and make for Morbihan under a press of sail. The night, which began with light south-westerly breezes and fine weather, ended with gale-force westerly winds, together with cloudy skies and heavy squalls. He held on until 3 a.m while Conflans was hove to, but was then forced to lie to until 7 a.m. with topsails backed. At dawn on the 20th Hawke was forty miles west by north of Belle-Île.

If there was a hero on the morning of 20 November it was surely Commodore Duff. There was nearly a disastrous breakdown in communication between him and Hawke, as the Admiral had sent a Lieutenant Stewart on the sloop Fortune to liaise with Duff, but Stewart reprehensibly got sidetracked into an attack on a French frigate. Only apprised at 3 p.m. on the 19th that Conflans was at sea, by superb seamanship Duff got his ships out to the open ocean. He discovered Conflans at dawn on the 20th and then led the French a dance back towards Hawke’s fleet. When Conflans saw Duff’s squadron, he ordered a general chase, with all ships cleared for action. Duff divided his squadron and stood inshore, sending half of his ships south and the other half north, hoping the French would disperse. Conflans took the bait and divided his force in three: the vanguard and centre were to pursue the two detachments of British frigates separately while the rearguard marked time and identified some strange sails just starting to appear on the seaward horizon. The French fleet was becoming badly scattered in the pursuit of Duff’s vessels when they suddenly changed tack and veered off. To his horror, Conflans was now aware of Hawke’s presence and frantically signalled to his own ships to abandon the pursuit of Duff and close up on the flagship. Hawke already had his ships in line of battle, all abreast ‘at the distance of two cables asunder’, and, seeing that the enemy was not in battle formation, immediately signalled a general chase. By noon the vanguard of the chasing Royal Navy vessels were just nine miles west of Belle-Île on a northerly bearing.

By now Conflans had signalled to his fleet to make for the entrance to Quiberon Bay in single file. For this decision he has been much criticised, especially by his own countrymen, and it is true that by this time he had allowed himself to be psychologically intimidated by Hawke, to the point where he feared the very thought of a sea battle, even though he was little inferior in numbers. His motives, as he later explained them, were threefold. He feared that he was no match for Hawke in the open sea on a lee shore in bad weather. Secondly, he thought that if he got all his ships inside Quiberon Bay before the British could enter, he could haul to the wind, form battle line on the weather side of the bay and thus redress his numerical superiority. Hawke would then be put in the tricky position of having to decide whether to come in close and risk the myriad shoals and reefs. Thirdly, Conflans could then embark the army of invasion and wait for the weather to drive Hawke away, as it had done twice already in this autumn campaign. But most of all, he considered that Hawke would not pursue him in such wild seas; to fight during a storm was against all the precepts of naval warfare. As he put it to the Minister of Marine:

The wind was very violent at west-north-west, the sea very high with every indication of very heavy weather. These circumstances, added to the object which all your letters pointed out, and the superiority of the enemy . . . determined me to make for Morbihan . . . I had no grounds for thinking that, if I got in first with twenty-one of the line, the enemy would dare to follow me. In order to show the course, I had chosen the order of sailing in single line. In this order I led the van; and in order to form ‘the natural order of battle’ I had nothing to do but take my station in the centre, which I intended to do . . . as soon as the entire line was inside the bay.