Of the two planning options he had submitted to Hitler in February to address the situation in Russia for the coming summer, von Manstein and his staff had indicated strong preference for, and had continued to press OKH to adopt, their ‘backhand’ proposal as offering the most effective operational solution. Their advocacy rested on the conviction that only this plan could best use what they believed to be the only trump card left to the Wehrmacht in its contest with the Red Army. Seen as the ‘superiority of the command leadership and fighting value of German troops’ in general, it was considered especially marked in the panzer and panzer grenadier divisions, which they regarded as the Wehrmacht’s ‘best sword’ in the conflict in the East. Given the actual conditions in Russia in the early spring of 1943, von Manstein was strongly of the view that only the ‘backhand’ plan, predicated as it was on maximizing the inherent flexibility and dynamism of German mobile formations, could generate the optimum conditions wherein this superiority could be exploited. Furthermore, while he never made any specific reference to this point, as von Manstein never seemed to equate the prowess of German arms with the equipment it employed, it nevertheless followed that only this strategy could properly exploit the qualitative and quantative improvement scheduled for the Panzerwaffe in the East during the spring and summer of 1943. This would see the panzer divisions taking delivery not only of new and superior tanks and Assault Guns, but also growing numbers of the improved, older types already in production. Adoption of the ‘backhand’ option would see a battle fought on German, and not Soviet terms.

There is no question that for von Manstein, the determining factor assuring the success of such a massive enterprise was his own expertise. Of this, as we have seen, he was in no doubt. Although Hitler was to express the view that ‘Manstein may be the best brain the general Staff has produced,’ in a negative context when speaking of his performance post-Zitadelle, it is nevertheless a judgement with which the Field Marshal would have concurred. Left to his own devices, he was convinced that he could always outfight the opposition, holding in contempt the limited ability of the Red Army’s command staff. However, his view – forged in the summer of 1941 when the Wehrmacht was running rampant in the opening months of Barbarossa – failed to take account of the qualitative change in the higher echelons of the Soviet leadership in the two years since. This over-estimation of his own ability magnified by his unshaken under-estimation of that of the enemy, was to make a significant contribution to the undoing of German plans for the summer of 1943.

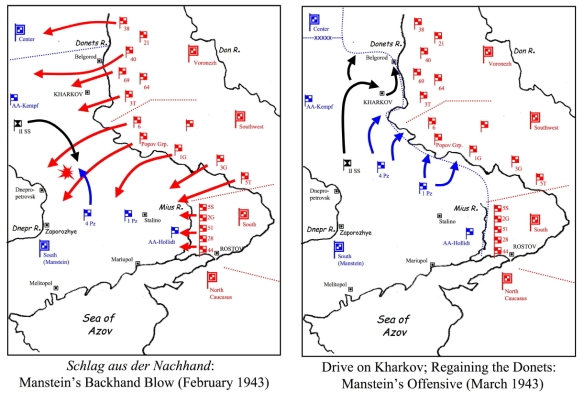

Nonetheless, if on 10 March Hitler needed to be reminded how effective his panzer and motorised troops could still be when their commanders were given their head, there could have been no better example than the success they were realising in the still-unfolding winter counter-offensive. While von Manstein was subsequently to express fulsome praise for the fortitude shown by the German infantry at this time, he was in no doubt that the key to German success in this operation lay in the manner in which the Panzer and supporting Motorized Infantry divisions had ‘fought with unparalleled versatility. They had more than doubled their effectiveness by the way they had dodged from one place to the next.’ Observing the maxim of concentrating scarce assets at the schwerpunkt, or decisive point, the commanders of these panzer formations had achieved a local superiority of 7:1 over a Red Army still coming to grips with the complexities of mobile warfare. This had enabled them to seize and retain the initiative, generating confusion in the ranks of the enemy by never giving them time to pause and regroup. Soviet units were then ground down and bled white in a tightly controlled battle of manoeuvre. Von Manstein envisaged his ‘backhand’ plan as repeating this on a much larger scale in the summer. The carrot he was dangling before Hitler was the possibility, so he believed, of repeating what he was at present realising in his winter counter-offensive, writ large.

As of 10 March, both Hitler and von Manstein were correct in their presumption that Stalin wished to return to the offensive with the onset of the dry season. The existence of the Kursk salient, so pregnant with military opportunity for either side, was identified by the Germans as providing the ideal springboard from which Soviet forces could launch a great offensive. There could be no doubt as to their intention: to realise in the early summer what they had failed to achieve in the late winter campaign – the destruction of the entire German southern wing on the Eastern Front.

The Field Marshal’s conviction that the Soviets would be prompted to launch their offensive sooner rather than later also stemmed from his conviction that destruction of Army Group South was the necessary prelude to Stalin’s wider political objective of securing the Balkans, a matter that he thought to be of overwhelming concern to the Russian leader.

In spite of the Grand Alliance, Stalin nursed deep suspicion that his Western allies, in particular the British, harboured their own ambitions in that region. Von Manstein believed the Soviet leader was thus strongly motivated to act quickly before any landings in southern Europe allowed them to gain control there. He argued that the forces the Soviets must assemble to realise such an ambitious plan would have to be huge. Should they be defeated in such an attempt – as he believed they could be – the consequences for the war in the East would be profound. Hoping that Hitler could be seduced by such a prospect into opting for what he believed to be the correct military solution to the strategic dilemma facing the Ostheer, he proceeded to set out the substance of his plan.

Its basic concept had not changed at all from the tentative design submitted to Hitler the previous month, when he had first broached the notion. Von Manstein later wrote:

It envisaged that if the Russians did as we anticipated and launched a pincer attack on the Donets area from the north and south, an operation which would sooner or later be supplemented by an offensive around Kharkov, our arc of front along the Donets and Mius should be given up in accordance with an agreed time-table in order to draw the enemy westwards towards the Lower Dnieper. Simultaneously, all the reserves that could possibly be released, in particular the bulk of the armour, were to assemble in the area west of Kharkov [elsewhere he is more precise, specifying in the vicinity of Kiev], first to smash the enemy assault forces which we expected to find there and then to drive into the flank of those advancing in the direction of the Lower Dnieper. In this way, the enemy would be doomed to suffer the same fate on the Sea of Azov as he had in store for us on the Black Sea.

However, whilst von Manstein could propose, only Adolf Hitler could dispose. In this matter, von Manstein’s knowledge of Hitler’s persona and modus operandi should have forewarned him as to his probable reaction. The ‘backhand’ proposal would be rejected by Hitler as being far too radical and audacious ever to be seriously contemplated. This was especially so, as, according to von Manstein himself, the German leader was by this stage of the War becoming exceedingly wary of embracing any mobile operation unless its ‘success could be guaranteed in advance’. Indeed, it had become the norm that whenever von Manstein advanced a plan predicated upon mobile warfare, Hitler’s immediate response was to quash the proposal with a comment along the lines of ‘We’ll have no talk of that!’

Furthermore, the execution of such a vast operation, governed as it was by the critical issue of timing, would require Hitler to devolve command and control of the forces involved to the field commanders, and especially to von Manstein. Although, as we have seen, he had been prepared to do this just a month before, that had only been because the Führer had been in extremis at that point in the conflict, and it was atypical behaviour on his part. Rather, Hitler had been moving to garner more and more control over the day-to-day operations in the field into his own hands, convinced that he was a far more capable judge of what was required in the conduct of the war in the East than his professional military.

In December 1941 Hitler had assumed the role of Commander in Chief of the Army (Heer) in December 1941 to add to his pre-existing position as Head of the Armed Forces (Wehrmacht). This extension of the notion of Führerprinzship from the political into the military domain, with its assertion of military control being vested in the hands of one individual, robbed the professional military of their prerogative to make command decisions. Hitler’s denigration of his general’s expertise was summed up by his observation to a former Chief of Staff in 1941: ‘This little matter of operational command is something that anyone can do.’

Evidence of Hitler’s wish to micro-manage the day-to-day running of affairs at the front, and the manner in which this served to rob even the highest of commanders of their capacity to exercise their professional military judgement, is conveyed in a photograph. It shows von Manstein at a table in his command train as it rattled through the Ukrainian countryside. Along with his command staff he is seen examining a series of maps, whilst over his left shoulder, and attached to the wall of the carriage in large letters on a poster, is the question Was würde der Führer dazu sagan? – What would the Führer have to say about it? This served, as intended, as an ever constant prompt from Rastenburg that whatever was decided had in the end to be both acceptable to and sanctioned by Hitler. Such an aide-memoire was to be displayed in plain sight wherever command decisions had to be made.

Inevitably, Hitler’s subsequent command style reflected the mindset he brought to bear on military problems. Thus, his operational decisions were governed more by the need to address concerns of personal prestige and ends of an economic and political nature than by realistic military necessity.

Coloured as his views were by his experience as a First World War frontkampfer, his rigid injunction to his troops was ‘to stand firm and fight, not one step back’. Hitler had first issued this instruction to his troops in the face of the Soviet counter-offensive before Moscow in December 1941, and it was soon to become the touchstone of his command style. Nicholas von Below, the Führer’s LuftWaffenadjutant throughout the conflict, was able to observe at close quarters Hitler’s modus operandi. He was later to observe in his memoirs:

Hitler forbade retreats from the front, even operational necessities to regain freedom of manoeuvre or to spare the men in the field. His distrust of the generals had increased inordinately and would never be quite overcome … he reserved to himself every decision, even the minor tactical ones.

In September 1942, this approach had been formalised when Hitler issued his ‘Führer Defence Order’. He had been stung into taking this action by his suspicion that the surrender of territory in pursuance of a flexible defence by units in Army Groups North and Centre in the late summer constituted evidence of a growing ‘retreatist mentality’ that pervaded the higher echelons of the Ostheer, which manifested itself at the first sign of pressure from the Soviets. In consequence, his demand to ‘stand and fight’ was elevated to the level of official doctrine. Thereafter, it became the basis from which he responded to every contingency, with adherence to this dogma being raised to the level of a virtue. Indeed, the fate of most field commanders with the temerity to ignore the Führer’s will in this matter and exercise their own initiative was more often than not, the sack. A fate which, in due course, even von Manstein, for all his brilliance, was unable to escape.

Backhand Blow: Kharkov 1943