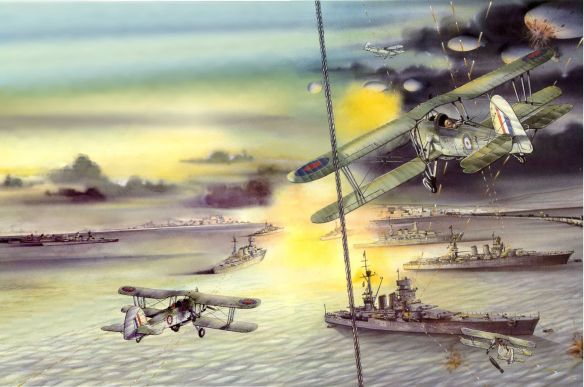

Determined to bring the war to the Italian Navy, Admiral Arthur Cunningham led a strong Royal Navy fleet to within 180 miles of the Italian port of Taranto. Swordfish torpedo planes from the fleet carrier HMS Illustrious attacked Italian warships in the harbor. Achieving complete tactical surprise, the “Swordfish” holed three battleships and a cruiser in exchange for the loss of just two of the old biplanes. The lopsided result deeply impressed all navies, newly revealing the striking power of naval aircraft and vulnerability of capital warships. The Japanese especially noted the similarities between Taranto and Pearl Harbor and carefully studied the Taranto raid as they prepared to attack the U. S. Pacific Fleet. Perhaps it may be interesting to record that a naval Japanese mission visited Taranto in Jan- and Feb. 1941.

Further proof that the Axis Powers were prepared to widen the war even more came with the signing of the Tripartite Pact linking them with Japan in late September and reports of a meeting held between Hitler and the Spanish Caudillo Francisco Franco at Hendaye in the Pyrenees on 23 October. Mussolini had struck both before and after these diplomatic initiatives had been arranged. His reckless enthusiasm for the Axis war effort had been shown firstly in a cross-border attack launched by his 10th Army on Egypt in mid-September and then by an invasion of Greece from across the Albanian border in late October. While his military forces didn’t cover themselves in glory in either of these two new theatres, the Regia Marina – now boasting six battleships – was not doing much more than engaging in mining operations, escorting convoys and skirmishing unsuccessfully with Cunningham’s Mediterranean Fleet. Worse was to follow for Il Duce and his fleet before November was out. During the night of 11-12 November, two waves of Swordfish aircraft from the carrier Illustrious had the temerity to attack the Italian Fleet as it lay at anchor in harbour at Taranto, crippling three of its battleships while slightly damaging a heavy cruiser and a destroyer into the bargain.

British navy raid on the principal Italian naval base, the fortified harbor of Taranto. Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham and Rear Admiral A. L. St. G. Lyster of the carrier Illustrious planned the operation, code-named JUDGMENT. The date for the raid was to be 27 October 1940, the anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar and a night with a full moon. Thirty Fairey Swordfish were slated to make the attack from the aircraft carriers Illustrious and Eagle. The Swordfish, though it was a 10-year-old biplane, was nonetheless a reliable, sturdy torpedo platform, especially effective in night operations.

A fire on the Illustrious, which destroyed several aircraft, forced postponement of the operation. Then the Eagle, which had sustained near misses from Italian bombs, was found to have been more seriously damaged than originally estimated.

As a consequence, the attack was delayed until the next full moon, when the raid was conducted by the Illustrious alone. Twenty-one Swordfish fitted with extra fuel tanks participated, with 11 of them armed with torpedoes and the remainder carrying bombs and flares. The torpedoes were modified to negate the effects of “porpoising” in the harbor’s shallow water.

At 8:30 P. M. on 11 November, Illustrious launched her aircraft some 170 miles from Taranto. All six of Italy’s battleships were in the harbor, where they were protected by barrage balloons, more than 200 antiaircraft guns, and torpedo nets, although the quantity of the latter was far short of the number the Italian navy considered necessary. The planes set out in two waves an hour apart. The first wave achieved complete surprise when it arrived at Taranto at 11:00 P. M. The pilots cut off their engines and glided in to only a few hundred yards from their targets before releasing the torpedoes against the battleships, which were illuminated by the flares and Italian antiaircraft tracers. Conte di Cavourwas the first battleship struck, followed by Littorio. In the second attack at 11:50, Littorio was struck again, and Duilio was also hit. In the two attacks, Conte di Cavour and Duilio each took one torpedo and Littorio three.

Conte di Cavour was the only battleship to sink, and she went down in shallow water. Italian tugs towed the other two damaged ships to shore. The cruiser Trento and destroyer Libeccio were both hit by bombs, but the bombs did not explode and caused only minor damage. Fifty-two Italian sailors died in the attack. The British lost two planes; the crewmen of one were rescued by the Italians.

As the maximum depth of water at any time in the harbour at Taranto was only 49′ (42′ has been quoted as the depth where the Italian battleships were moored). The torpedoes used at Taranto were a mix of contact and magnetic pistols. The greatest damage was done by the torpedoes equipped with the magnetic pistol and which were set to run at 34′.

Conte di Cavour was later raised and towed to Trieste to be repaired, but the work was not completed and she was never recommissioned. The Littorio was overhauled by March 1941, and the Duilio, which was transferred to Genoa, was repaired and returned to Taranto in May 1941. The Taranto raid thus deprived Italy of its naval advantage and at least temporarily altered the Mediterranean balance of power, and it also underscored the effectiveness of naval aircraft.

Taranto, only one-third of the planned torpedo netting was actually in place by the time the attack came in November 1940. A further, and somewhat fortuitous, chink in the Italian armor was the fact that a major storm had blown a significant number of the barrage balloons loose from their moorings. These, too, had yet to be replaced, with the result that there were several sizeable gaps in the balloon barrage– and the British planes in fact slipped through at least one of these gaps in making their attack.

The chief Italian failing at Taranto in terms of “nature of means” was their lack of radar. In the pre-war years, the Italians had gone with the cheaper alternative of sophisticated listening devices as early-warning for their coasts (despite the fact that Marconi, the inventor of wireless telegraphy, had demonstrated a working radar set for the Army a couple years before the war). The listening devices indeed picked up the first wave of British aircraft while they were still about 30 miles offshore, but once the enemy planes got over land there was no way to track their direction.

Everyone on the British side was delighted with the results of Operation Judgment, since it appeared to have eased the Allied naval position in the Central Mediterranean, by reducing the risks to their convoy traffic and boosting morale in their own ranks, while complicating the Italian strategic situation and deflating the enemy. Cunningham summed up the cost-benefit analysis of the entire operation perfectly by stating: `As an example of “economy of force” it is probably unsurpassed.’ He was not prone to exaggeration and his enthusiasm for taking the fight to the Italians was infectious.