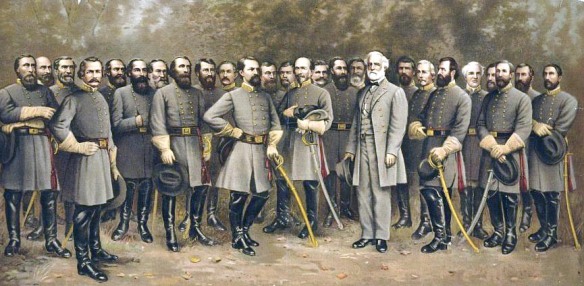

Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Generals

When Gen. Robert E. Lee established a stalemate in Virginia with the siege of Petersburg, and the indirect siege of Richmond, the heartland of the older south presented the appearance of a continuing existence as the Confederacy. There was an obvious recession from its vast military front of the year before, when the nation had armies in the field from Pennsylvania to the lower Mississippi. But there were no serious indentations on its thousand miles of Atlantic coastline, nor penetrations in its productive access from the ocean to west of the Alleghenies. West of the mountains, the army under Sherman presented the only serious threat from Tennessee to the Gulf of Mexico, including stretches in Alabama and Mississippi westward along the Gulf. Though isolated across the Mississippi River a separate domain existed in Texas (ingeniously supplied by trading through Matamoras) and armies operated in the lost lands of Arkansas and Missouri.

In western Georgia, the railroad junction city of Atlanta occupied on its front the equivalent position of Richmond in the East. No armies had previously approached this center, where strong outlying works were built and where Governor Brown promised he could field the thousands of state militia whose votes had saved them from conscription, Military actions of various size radiating out from the Atlanta area gave an impression of military stability to the Confederate West. A brilliant victory by Forrest at Brice’s Crossroads gave Old Bedford in his sphere the quality of invincibility which Lee sustained in his.

This appearance of stability was illusory. In the West there was no general with the prestige nor the diplomacy of Lee, who could gain compromises with the commander in chief and, in extreme emergency, break the barriers of the departmental system. As in Virginia even Lee had been able to circumvent the system only to the extent of fending off disaster and gaining a stalemate, in the West, where the commander in chief ruled supreme, nothing could save the Southern armed forces from the consequences of departmentalization.

This is not to imply that Jefferson Davis’s control of the military establishment and its policy caused the collapse of the extemporized agrarian Confederacy before the might of an industrialized nation four times its size. Libraries are crowded with volumes explaining the reasons why the quickly formed confederation was unable to maintain itself against physical force long enough to be granted its independence. Yet, exhibiting an heroic quality of the spirit to endure physically weakening and mentally discouraging hardships, along with a remarkable ingenuity and inventiveness, its soldiers and citizenry maintained armies in protection of its vital areas in June, 1864. It was in relation to those armies and the remaining key positions that Davis’s operation of his system doomed the Western Confederacy, regardless of what other forces may have been at work.

With the example of the Richmond-Petersburg front before his daily gaze, the obsessed President effected a faithful reproduction of the arrangement at Atlanta. Only minor details were changed, according to the different personalities. Atlanta’s department was sealed off from departments to the east and to the southwest, and Joe Johnston, the commander of the main army, could not obtain troops from adjoining departments to concentrate against the enemy’s main objective.

Within this standard procedure, the irrational element was Davis’s sudden turn to offense for defense-minded Joe Johnston, outnumbered two to one. As Joe Johnston’s reasonable protests were regarded merely as a subordinate’s efforts to thwart the authority of his superior, the General’s request for the one solution to his problem was dismissed as an excuse. But Johnston requested the one move feared by Sherman: Forrest turned loose on the Federal line of supplies.

It happened that the commander of the department to the southwest of Atlanta did not wish to relinquish Forrest. The great cavalry raider could serve better by guarding property in Alabama and Mississippi. Though it was natural for Davis to give departmental stability preference over a strategic objective, the case involving the Department of Alabama and Mississippi was special.

Civilian authorities and newspaper editors joined General Johnston’s appeal for Forrest to operate on Sherman’s communication, and Davis’s back stiffened at the suggestion that those persons knew more than he did. Also the department commander, Major General Dabney Maury, a regulation-style West Pointer, was a gentleman both by birth and act of Congress, while Bedford Forrest, an unlettered ex-slave dealer, was a rough customer who made up his own rules of war as he went along.

It was not, as it has sometimes been made to appear, that Davis missed the native genius for warfare uniquely possessed by Forrest. Davis showed no appreciation of any of the “originals” in the Confederacy, and little interest in accomplishments which did not fit into the system under his control.

Stonewall Jackson was a discovery of Lee, who personally gave that unexpected genius his chance while the commander in chief was preoccupied with Joe Johnston in their 1862 misunderstanding. Outside Davis’s area of concern, semi-autonomous domains were operated by Gorgas in ordnance, General Anderson in the cannon-producing Tredegar Iron Works, and young Dr. McCaw at Chimborazo Hospital, then the world’s largest military hospital and the most advanced of any kind. (The President’s bureaucratic medical director, Dr. Moore, reproached McCaw for negligence in his morning reports during the period when Chimborazo Hospital was achieving the lowest mortality rates in medical history until the sulfa drugs of World War II.)

Almost forgotten in the Navy Department, Secretary Mallory and Matthew Fontaine Maury, the oceanographer, were very imaginative in concepts and inventive in technology. The Confederate naval forces introduced the first ironclad warship, the first combat submarine, were extremely advanced in the use of underwater torpedoes and highly original in the production of the ram (notably the Arkansas and the Albemarle), designed to nullify the superior numbers and equipment of the United States naval forces.

This type of man, who recognized the need of new concepts and new methods adapted to the Confederacy’s specific circumstances, appeared in numbers and in a diversity of fields surprising in an essentially agricultural people fighting for an anachronistic culture. As their achievements were not interrelated in a single policy, the special gifts of these men were as wasted in their areas as was Forrest’s in the West. The misuse of Old Bedford was more dramatic because it was a focus of attention during a decisive campaign.

Jefferson Davis was acting according to form in restricting the Confederacy’s greatest raiding force to fending off enemy cavalry dispatched specifically for the purpose of keeping Forrest from Sherman’s lines of communication; and he merely repeated his pattern in Virginia when he refused to recognize a cause-and-effect strategy. The effect in Georgia was to permit Sherman to proceed to Atlanta untroubled by disruption to his supplies.

Since even Sherman, with his physical superiority, could not successfully attack dug-in troops at that stage of defensive warfare, Johnston executed an extremely skillful retreat and held the cautious enemy to a snail’s pace. However, by the time he reached the environs of Atlanta without striking an offensive blow, he was ruined with the President.

It is true that Johnston was secretive and evasive with his superior. Though Johnston talked then and later vaguely of his “plans,” he could only give ground, conserve his army, and hope for an opening in which he could deliver a counterstroke. The mutuality of the loathing between the two former West Point college mates made it impossible for Johnston to confide this to the President.

Someone should have told Davis that this was not the time to try to make up for all the lost opportunities of the past. A small army had been diverted from operations in the Lower South to help Sheridan drive Jubal Early out of the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley. This not only helped stabilize the military situation in the Lower South but reduced Sherman’s supply of the replacements for losses which Grant had drawn upon. Of all times to hold on, this was it.

But Davis had seized upon the idea of an offensive as the one cure, and to get to the bottom of the matter with the recalcitrant Johnston, he sent Braxton Bragg to Atlanta. Bragg, of course, told the President what he wanted to hear, and General Joseph E. Johnston joined Harvey Hill in the growing legion of generals without commands.

Against Lee’s advice, Davis then appointed combative John Hood, whose skill at maneuvering for personal advancement exceeded both his military abilities and good judgment. Hood was a fine fighter of troops and a better soldier than his disastrous career as army commander would indicate. However, having won the position of army commander on the understanding that Davis’s offensive would be mounted, Hood was precommitted to attack a superior force.

It was not that Hood’s offensive around Atlanta was poorly conceived. As even Grant’s mighty hosts showed in Virginia, the times in the war were unfavorable for offense against an alert, determined enemy. Ten days after Hood’s appointment on July 18th, the poor, doomed men of the Army of Tennessee had attacked themselves out of Sherman’s path to Atlanta. The siege lasted little more than one month, and on September 2nd Sherman’s triumphant army marched into the half-wrecked city.

The illusory stability in the Lower South was immediately exposed. With the fall of Atlanta the bottom dropped out of the Confederate West. What had seemed in early July to be a broad front of Confederate resistance was suddenly reduced to the single hold-out of Lee.

To the North, the good news of Atlanta’s fall in early September obliterated the already dimming memory of Grant’s catastrophic losses back in June. Within three weeks more, before the end of September, the army collected under Sheridan in the Valley finally overran Jubal Early’s little force.

All the enemies accumulated by bitter Old Jube blamed him for the debacle. With a simple devotion not suggested by his harshness to others, Early accepted the calumny rather than excuse himself on the grounds of the disparity between his force and the enemy’s. After carrying the war to the enemy for three months, at the end he had little more than ten thousand men of all arms against close to fifty thousand under Sheridan.

Such personal details, unknown to either side, had no relation to the effect of the loss of the Shenandoah Valley. Though the South tried to explain away the disaster by making Jubal Early the goat, none could escape the costly loss of the supply center nor the moral effect of this defeat in the region associated with Stonewall Jackson’s great days. In the North, the sweeping aside of Early’s remnants redounded to the glory of Sheridan, who was finally able to enjoy an uninterrupted spree in the destruction of personal property. By then, with the war suddenly, or so it seemed, contracted to a single siege, obviously no Democratic peace party had a chance in the November elections. The Lincoln Administration would be supported to the finish, and the end did not come mercifully.

With Sherman in Atlanta and the Confederate forces outside, Hood occupied the Federals until mid-November. Then a concentration of Federal forces formed an army to contain Hood’s troops, while Sherman, after burning Atlanta, turned loose his soldiers on a march of pillage and destruction across Georgia to the port of Savannah. Hogs, chickens, milk cows were slaughtered, horses taken and barns burned. Family stores of bacon and corn meal were rooted out of hiding places and, if the women protested or the officer in charge of the raiding felt porky, the house was burned. By Christmas, when Savannah was occupied, Hood had wrecked the Army of Tennessee at Nashville, and the ragged, starving survivors were retreating into Mississippi.

In February, 1865, Sherman’s army, with the men then hardened by vandalism into a mob, started northward through South Carolina with the self-declared purpose of vengeance on the breeding ground of secession. The soldiers were allowed full license to loot, and they raged like hoodlums through private homes, taking jewelry, silver, whatever struck their fancy. Home-burnings became more commonplace until the state capital at Columbia was reached, on February 17th, and this city was, according to Sherman, “totally burned.” On the same day the ante-bellum, cosmopolitan planters’ paradise of Charleston was entered, bringing to an end its four-year-siege from the harbor.

The month before, Fort Fisher, guarding the approach to Wilmington, North Carolina, had fallen to an amphibious attack. Whiting, who had failed in the field with Beauregard at Petersburg, gave his life in leading an inspired defense of the fort strengthened by his engineering skill. Braxton Bragg, with no functions left as Military Advisor to the President, was officially in command of the department, with headquarters at Wilmington. On February 22nd, five days after Charleston was occupied, Wilmington was entered, and the last port on the Atlantic was closed. The Confederacy was isolated from the world.

After that, the pace to the finish was accelerated. On land Sherman started northward again, entering North Carolina. Another army started eastward from the coast. Cavalry raiders struck in from the West, terrorizing isolated families and running off stock. Joe Johnston was plucked from exile and given command of a heterogeneous collection of troops, including remnants of Hood’s army, assembled in North Carolina in Sherman’s fiery path. This force “melted away,” Johnston said, before his eyes. At every nightfall men simply walked off, the artillerists taking their personally owned mounts, to get home and look after their families.

Scattered fighting continued in stretches of the Lower South, and the small empire in Texas held on to its lonely existence. But the core of the Confederacy, as it existed in mid-June when Lee set his army to withstand the siege, had shrunk to the two hundred inland miles between Grant’s and Sherman’s armies.

By March, the Richmond-Petersburg fort had become an island, with its lines extended to more than thirty miles. Finally the lines were stretched too far for the declining army to man the works. The masses of the enemy poured over in waves and at last, eleven months after the campaign had begun, Lee was forced into the open.

He had nowhere to go and nothing to go with. When his survivors escaped from the overrun lines, Richmond was uncovered. Troops of Weitzel’s command, established in a permanent fine north of the James River, marched into the burning city, with the bands of a Negro division playing “The Year of Jubilee.”

The evacuation of Richmond removed the last conceivable justification for Lee’s army to remain in the field. Davis, however, fled the capital into some private world of his own, where he intended to carry on the resistance indefinitely.