During the uneasy inter-Allied conference at Chantilly in November 1915 the policy of coordinating Allied moves in the west and on the Russian fronts had been re-confirmed. Whatever Nicholas II’s generals had thought initially about their role as decoys to relieve German pressure in Flanders and, to a lesser extent the Austro-Hungarian threat against Italy, their reliance on Western arms shipments again forced them to launch an offensive – this time to coincide with the planned Allied offensive on the Somme, which was intended to develop into the ‘big push’ that would end the war. With OHL giving priority to building up men and munitions for Falkenhayn’s planned killing blow at the exposed fortress-city of Verdun in the spring – nobody then guessed that nearly a million men would die there, mostly blown to pieces by high-explosive shells – on the Russian fronts the winter 1915–16 passed in a series of small attacks of no great moment except to the thousands of men who were wounded, taken prisoner, died in combat or succumbed to exposure.

The Tsar paid a visit to several units on the south-western front, one of them 8th Army, commanded by General Brusilov, a slim and wiry cavalryman whose army career went back to the Russo-Turkish war of 1877. When the bodyguards’ train arrived one hour before the royal train, the commander of the guard expressed concern that Austro-Hungarian aircraft might bomb the units to be inspected during the visit, putting the Tsar’s life at risk. Brusilov pointed out that the low cloud would keep aircraft on the ground, so there was no danger of that happening. Accompanying the Tsar and crown prince, he noted how stiff and awkward they were when talking to the soldiers. A few overdue medals were presented and the royal train disappeared. Describing this in his memoirs, Brusilov contrasts this pointless visit with the fact that the commander of the south-western front, General Ivanov, visited the front so rarely that he had no idea of the morale or capability of his troops. He not only failed to make any preparations for an offensive, but also openly voiced his opinion that his troops could not defend their own lines, if attacked. This was in distinct contrast with Brusilov, who was already mapping out plans for 8th Army to attack and drive Austrian 4th Army under Archduke Joseph Ferdinand back to the Styr and Stockhod rivers. His only reservation was that his right flank needed to be protected by 3rd Army, which was not part of Ivanov’s command because it fell under the western front, commanded by General Aleksei Evert. Evert was an imposing man of fifty-nine whose chest was covered in medals and stars, but who was equally as lacking in fighting spirit as Ivanov. As time would tell tragically, Brusilov was right to suspect Evert of failing to support an attack by a neighbouring unit or army, even when ordered to do so.

As a sop to Brusilov, front commander Ivanov allotted sotni of Cossack cavalry to patrol on 8th Army’s right flank. As Brusilov pointed out, they were intended for fast-moving manoeuvres in open country and could not be of much use in the Pripyat marshes there. Instead, these bands of horsemen mainly roamed about behind the Russian lines, raping and looting the property of the remaining inhabitants. Their only successful operation against the enemy that winter was a raid by three dismounted sotni, who used local guides to follow secret paths through the marshes and raid the HQ of a German infantry division, capturing several officers including the commanding general. Generally, officer POWs were well treated when captured by regular troops but these prisoners must have been ill treated by the Cossacks because the general committed suicide, cutting his throat with a razor after receiving permission to shave himself. At the end of the winter, these irregulars were disbanded, with some men sentenced to death by court martial or exiled to hard labour for robbery and rape. As Brusilov commented in his memoirs without actually mentioning Ivanov, it is amazing how many otherwise intelligent people have stupid ideas!

He, as commander of 8th Army, spent the winter overseeing the construction of better shelters, both for the men’s comfort and health, and to protect them from artillery fire when winter gave way to spring and the front heated up again. However, when he later saw the reinforced concrete shelters constructed by the Austrians, he admitted that they were a great deal more impressive – especially the plentiful bathhouses which enabled the enemy troops to keep cleaner and less lice-infested than Russian infantrymen. It is true that there was less disease in the tsarist armies than in previous wars, yet outbreaks of typhus, cholera and smallpox recurred, as Florence Farmborough was to find. Nevertheless, Brusilov considered that morale was good, while regretting the lack of sufficient heavy artillery and aircraft for reconnaissance and artillery observation on south-western front and a total lack of armoured motor vehicles. These last had been promised from France, but did not arrive during the time he was commanding 8th Army.

When Falkenhayn at OHL began his Verdun offensive on 21 February 1916, Tsar Nicholas informed his generals that, in keeping with the ‘request’ of General Joffre at Chantilly, a new offensive must be launched on the Russian fronts to immobilise German forces that could otherwise be transferred to Verdun. The most promising sector for such an attack was on the northern front in the area of Lake Narotch (modern Narach in Belarus), where elements of two Russian armies totalling 350,000 men faced a German line held by General Hermann von Eichhorn’s 75,000-strong 10th German Army. The northern front was commanded since von Plehve’s health had given way by General Aleksei Kuropatkin, a man so disgraced during the defeat by the Japanese a decade earlier that he should not have been given any command, in Brusilov’s opinion. Grand Duke Nikolai had rightly refused to appoint Kuropatkin, but had been over-ruled by the Tsar when he took over as supreme commander.

On 17 March at the lake – now a peaceful and verdant tourist area – Russian 2nd Army opened the offensive. With conditions seemingly favourable for a rapid victory to raise Russian morale and please the French, a two-day preparatory bombardment that used up much Russian ammunition was so badly directed that it caused scant damage to the German artillery. The price for this was paid when the infantry went in, in tightly grouped squads. Not only did they suffer as obvious targets for the German artillery, but the failure to spread out and use what cover was available caused a terrible slaughter from well-sited German machine gun positions with interlocking fields of fire. The few local gains made were all subsequently lost in German counter-attacks. Early in April, this sector of the front went quiet, having cost another 100,000 Russian casualties, including around 10,000 men who died of exposure in the harsh weather conditions. For this further blot on his record, Kuropatkin was later relieved of his command and sent to distant Turkestan as its Governor-General.

On the day before the Lake Narotch offensive opened, Brusilov received an encoded telegram from Stavka, in which Chief of Staff General Mikhail Alekseyev informed him confidentially that he was being appointed commander of the whole south-western front, replacing Ivanov, who had had a nervous breakdown – as a result of which he was being transferred to a sinecure post in the Tsar’s household. Ten days later, 120 miles behind the lines at Berdychev, Brusilov arrived at Ivanov’s HQ to take formal command of the whole front. He found Ivanov living in a railway carriage, ready to depart, weeping and asking repeatedly why he had been sacked. This embarrassing behaviour continued at dinner in front of his staff. As Brusilov dryly commented, he could give no reply to Ivanov, not being privy to the precise reasons for Alekseyev’s decision.

The Tsar had not been keen on Brusilov’s appointment, but refrained from blocking it. He arrived on another tour of the south-western front and insisted on inspecting 11th Army, speaking to the troops paraded for the occasion without a glimmer of charisma. As Brusilov commented, the speech was not such as to lift the spirits of the men. During the visit, enemy aircraft appeared but were driven off by Russian artillery. To his credit – or perhaps his lack of imagination – the Tsar remained with 11th Army for two days and nights. Kaiser Wilhelm was also visiting German troops on the other side of the lines, where his gruff man-to-man manner had always gone down well with the rank-and-file, although on this visit he noticed for the first time an unpleasant surliness in his troops due to the high casualties, the harsh weather on the Russian fronts and news from home of social unrest and the imprisonment of revolutionary socialists like Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg.

Brusilov’s next meeting with Tsar Nicholas was on 14 April, when attending his first meeting of Stavka as commander of the south-western front. This took place in Mogilyov (modern Magilyou in Belarus), described as a depressing town, chosen because it had some large buildings to accommodate the various staffs, and was presided over in his usual indecisive manner by Nicholas. Among the officers present was General Evert, commanding the Russian western front, who supported Kuropatkin’s claim that the failure at Lake Narotch had been due to inadequate reserves of artillery shells. They both agreed that this made further offensives pointless. As chief of staff, Alekseyev nevertheless ordered a summer offensive on the northern front by 2nd and 10th armies when new conscripts had replaced casualties and missing in action, to bring strength up to between 700,000 and 800,000 men. The right flank of this offensive would drive on Vilna while the rest of this force, outnumbering the Germans by a ratio of 5: 1 or better, was tasked with playing a waiting game to interdict movement of enemy formations against the right flank. But there was a trade-off. There always was with Alekseyev, an unpretentious man of humble origin who tried to avoid contact with his own staff and felt embarrassed if he did not pay his own mess bill, unlike many of the noble officers he commanded, who took it as of right that the army should feed them. In his favour, it has to be said that he had effected an excellent clear-out of the aristocratic cavalrymen who had scavenged at the table of his predecessor, yet was unable to impose his will at times like this. He agreed to a two-month delay and accepted the need for 1,000 more heavy guns for the preparatory bombardment.

At this conference, Brusilov surprised the other front commanders by volunteering to direct a simultaneous offensive on his front to prevent the enemy moving reinforcements on the railway network in Austrian Galicia to reinforce their positions on the northern front. After he refused to be deterred by Alekseyev’s warning that he could expect no priority in reinforcements or materiel, Kuropatkin and Evert rubbished the idea of Brusilov’s offer. At dinner that evening one of the senior generals – in his memoirs, Brusilov does not name him, for whatever reason – gave some advice: ‘You’ve just been appointed front commander. Your reputation stands very high, why take a risk like that which could tarnish it and cancel out all your achievements so far?’ Brusilov replied that he saw it as his duty to attempt to win the war, whatever the problems of manpower and materiel.

He reasoned that the crippling shortage of artillery, rifles and ammunition that had beset the Russian armies earlier in the war was being steadily overcome, and that the situation would continue to improve because the retreat of 1915 had shortened the front, making re-supply more rapid, and Russia’s indigenous armament industry was at last producing 1.5 billion cartridges and 1.3 million rifles per annum, with a further 2 million in process of importation from abroad. The standard of recruit training was also much improved and a policy of initially drafting ‘new meat’ to quiet sectors of the front meant that raw recruits no longer de-trained to find themselves thrown into combat the next morning. Ivanov, still not recovered from his breakdown, was in habitual negative mood and asked the Tsar to veto Brusilov’s proposal. As usual, Nicholas refused to throw his weight on either side, so Brusilov left Stavka to present his plan to his own staff.

Alexei Brusilov was unlike most of his fellow generals in the Russian forces in not being an alumnus of the General Staff Academy. He also did not share their conviction that endless bayonet charges would win the war by killing more of ‘them’ than ‘us’. To his way of thinking, new materiel like tanks and aircraft offered more efficient possibilities. To some extent, this was because he was familiar with Western European military thinking, having visited the German, French and Austro-Hungarian cavalry schools before the war and had made his own independent analysis of the Japanese defeat of Kuropatkin and his army commanders Rennenkampf and Samsonov in the war of 1904–5. Britain’s senior soldier of the Second World War, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery considered that Brusilov was one of the seven outstanding commanders of the First World War. It is certainly arguable that the eventual result of the war in the east might have been very different, had Brusilov been given overall control at the outset and authority to override the blinkered nineteenth-century thinking of the generals senior to him, particularly at Stavka.

The third generation of his family to serve in the tsarist army – his grandfather had fought against Napoleon in 1812 – Alexei was born in 1853 in Tiflis of a Russian father and Polish mother. Orphaned young, he was raised by relatives in Georgia until the age of 14, when he was sent to continue his education with the prestigious Corps of Pages in Saint Petersburg – a promising first step to a military career. There, a tutor’s report on him contained the comment: ‘Of high potential, but inclined to be lazy.’ The slur hardly fits with the man he showed himself to be in 1916. His rejection by the Tsar’s prestigious guards regiments had more to do with lack of family money to subsidise life as a guards officer than any character defect. Instead, he was posted with the rank of ensign to a lowly dragoon regiment back home in Georgia.

There, keenness and efficiency saw him rapidly promoted to regimental adjutant with the rank of lieutenant. In the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 he was awarded several medals and ended the war as a captain. He must have caught the eye of some senior officers, for this was followed by a posting to the prestigious cavalry officer school in St Petersburg, leading to an appointment on the staff of the college, where he spent the next thirteen years. By 1902 he was a lieutenant general commanding the school. It was at this time he was able to travel to France, Austria-Hungary and Germany, ostensibly to study horse breeding and other harmless matters, but also to observe first-hand, in Germany and Austro-Hungary, the manoeuvres of the very armies he would almost certainly be confronting one day, and thus gaining an appreciation of their commanders’ thinking.

Although not as shattering to Russian society as the 1917 revolution, the revolution of 1905, triggered by Russia’s defeat and appalling death toll in the Russo-Japanese war, caused much disruption of life in St Petersburg, as it then was. Coming after the death of his first wife, this caused Brusilov to seek a posting away from the capital. He was rewarded in 1912 with appointment as deputy commander-in-chief of all Russian forces in the strategically important Warsaw Military District. It was, however, not a happy time because his superior, Governor-General Georgi Skalon, was an autocrat whose brutal repression of civil unrest there at the time of the 1905 Russian revolution had led to an attempt on his life by Polish nationalists. Brusilov simply did not fit in the rigid pomp-and-circumstance hierarchy of Skalon’s command and had himself transferred to Kiev in the Ukraine.

On mobilisation in July 1914, he was promoted to command Russian 8th Army on the south-west front in Galicia, which smashed its way through the opposing Austro-Hungarian forces, rapidly advancing nearly 100 miles, but had to retreat in the general withdrawal after Tannenberg. Early 1915 saw the same script replayed, with Brusilov’s spearheads advancing through the Carpathian passes to threaten Budapest until forced back in the general retreat. Never the sort of commander to stay back at HQ all the time, he had thoroughly reorganised 8th Army before handing over command to his successor and made a complete tour of inspection of the whole south-western front after his promotion to front commander. He felt confident that, although his two previous successes had been forfeited by the shortcomings on his flanks and shortages of materiel, this time Evert would have to attack simultaneously, so that he could again push the opposing German and Austro-Hungarian forces back to the Carpathians and this time hold them there.

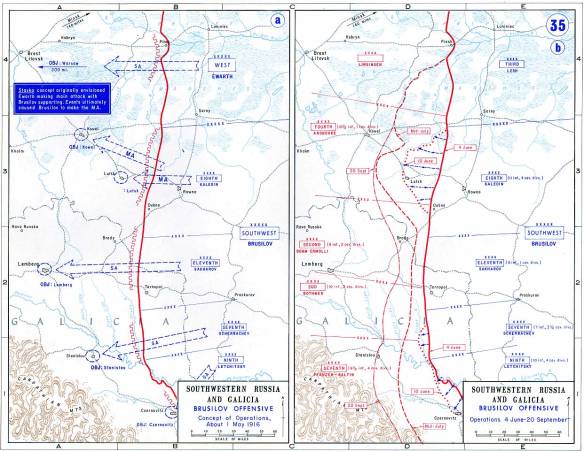

Brusilov disagreed with the customary Russian practice of concentrating an offensive on a small sector of the front for the good reason that this left the advancing troops vulnerable to counter-attack on the flanks. What he was planning, was an attack that would hit the enemy in many places over the whole 280-mile length of the south-western front, reasoning that this would prevent the enemy moving forces to strengthen weak positions, one of which would give way and lead to a collapse. His artillery was also to be deployed differently, not to make saturation barrages but to target strategic points such as road junctions and command posts of the German units they were facing. Brusilov even accepted the transfer of some divisions to Evert’s front on the assumption they would be attacking at the same time as he did and securing his right flank.

On 17 April at front HQ in Berdychev he therefore informed his four army commanders that the offensive would be launched simultaneously in a number of places from the southern limit of the Pripyat marshes down to the Romanian border, with 8th Army targeting particularly the railway junctions at Lutsk and Kovel – an axis that had the potential to split the opposing CP forces in two. The army commanders’ reaction mirrored that of the generals at Stavka. In fairness to them, the enormous scale of previous losses in this theatre and the fact that every advance made had, sooner or later, been repulsed by the enemy, had eroded whatever aggressive spirit they once had. Traditional military thinking was that an attacking force should be roughly three times as strong as the defenders. With a manpower ratio of roughly 1:1 – each side had about 135,000 men in the line on this front – General Aleksei Kaledin, commanding 8th Army because of family connections with the Tsar, who had blocked Brusilov’s choice of appointee for that post, said openly that the offensive could not succeed. He was pulled up sharply by Brusilov, who reminded him that he had just handed 8th Army over to him and was personally aware that it was well prepared to attack – and also that he was familiar with every mile of 8th Army’s front. The commander of 7th Army, General Dmitri Shcherbachev was the only one initially favourable to Brusilov’s plans, and even he allowed himself to be talked round until Brusilov found all four of his army commanders speaking out openly against them. He then informed them all that he was not asking for their advice, but ordering them to prepare the offensive.

His four armies gave him forty infantry divisions and fifteen cavalry divisions. The four opposing armies they would be taking on consisted of thirty-eight infantry divisions and eleven of cavalry. In artillery, Brusilov’s 168 heavy guns and 1,770 light guns roughly matched the Austro-Hungarians’ 545 medium and heavy guns and 1,301 light guns on that front.

Time spent in preparation is seldom wasted. The old maxim from Caesar’s day, or earlier, was Brusilov’s credo. He commenced by ordering reserves brought forward all along the line, so that enemy aerial reconnaissance could not determine at what point the offensive was likely to come. Once ‘up’, these troops were set to excavating sheltered places d’armes or assembly areas for thousands of men, with the displaced soil piled up into berms running parallel to the front line, both to impede observation from the ground and to afford some protection against incoming artillery fire. From these areas, communication trenches were dug to the front lines. Not content with that, Brusilov ordered saps, or tunnels, to be dug out into no man’s land. The purpose of these was to bring the jumping-off points for his infantry within 50–100yd of the enemy lines and thus radically reduce the time they were exposed to machine gun fire during the assault.