The Nguyen Hue Offensive of 1972

Before the Communist offensive in 1975, the ARVN, with a total of about 1 million men, consisted of 11 infantry divisions, one airborne division, one marine division, 15 Ranger groups, 66 artillery battalions, four armored brigades, and various combat support units. The Air Force had four air divisions with 1,000 aircraft and 800 helicopters, totaling 40,000 men. The Navy had 39,000 men and was equipped with 1,600 vessels of all sizes organized into one Sea Task Force and numerous riverine squadrons.

After the 1968 Tet Offensive, in which the VC suffered heavy losses, the North Vietnamese Army brought troops from the North to replenish the depleted VC units or to replace them entirely. By 1972, it was estimated that 75 percent of the soldiers in VC units came from North Vietnam. At that time, the NVA/VC forces in the South amounted to approximately 300,000 men, consisting of 200,000 regular troops and 100,000 local forces. The main regular force consisted of 20 infantry divisions plus various combat support units.

Thus, after the withdrawal of US and allied (South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand) forces under the Vietnamization program beginning in 1971, the ARVN faced the NVA from a presumed position of strength – outnumbering Communist forces roughly three to one. However, in reality the situation was much more precarious, for accepted wisdom contends that government forces must achieve at least a ten-to-one ratio to be able to defeat an insurgency. This is because the greatest portion of that force could not be used to face the insurgents, but instead would be used to protect the populated areas and to safeguard key logistical installations, airports, bridges, and lines of communication.

It is remarkable that the ARVN, under heavy odds, had almost won the war toward the end of 1971. After having destroyed, in tandem with their American allies, more than half of the VC’s regular forces during the Tet Offensive, the ARVN rooted out the VC’s political and administrative infrastructure in the hamlets and villages of South Vietnam. It is more remarkable that this same army, with pivotal American air support, held its ground and defeated the NVA’s multi-division Easter Offensive in 1972, achieving perhaps the biggest single victory of either the Indochina War or the Vietnam War.

It was indeed the 1972 Easter Offensive that served as the best indicator of the ARVN’s potential and the way forward to victory in the Vietnam War. The conflict had changed fundamentally since the beginning of Vietnamization. American combat forces were, in the main, gone from the conflict, leaving the ARVN to face both the irregular war in the countryside and the big-unit war of the North Vietnamese. Though American troops were leaving, their massive air support remained behind to work in tandem with their South Vietnamese allies. It was to be a fruitful partnership, American firepower and economic support and South Vietnamese manpower, a partnership that would prove well nigh unstoppable.

For their part, the NVA/VC would no longer choose to run and hide in their cross-border sanctuaries. Instead, Hanoi decided to launch the 1972 Great Offensive to capture SVN by force. In lieu of continuing the traditional Communist strategy of guerrilla warfare culminating in a combination of conventional warfare and popular uprising to overthrow the South Vietnamese government, NVN decided to literally “burn the stage” (đốt giai đoạn in Vietnamese) by simultaneously launching multidivisional assaults on three fronts: Quang Tri and Thua Thien provinces in MRI, Kontum province in MRII, and Binh Long province in MRIII. According to the Communists’ plans, if these offensives proved successful, Hanoi would use these new bases as a springboard for the final conquest of SVN.

On the northern front, the attack began on March 30, 1972. After heavy artillery preparations on the ARVN’s 3rd Division’s positions, the NVA’s crack divisions, 304, 308, and 324B, supported by one artillery division and two armored regiments, crossed the Ben Hai River, which separated the two Vietnams under the 1954 Geneva Accords. This major offensive coincided with the arrival of the first seasonal monsoon storm, which prevented tactical air support to the defending units.

At the time of the attack, the ARVN’s regular forces in Quang Tri province consisted of the 3rd Infantry Division reinforced with the 147th Marine Brigade, the 5th Ranger Group, and the 1st Armored Brigade. The 3rd Division was the ARVN’s youngest division. The majority of its soldiers were deserters, draft dodgers, and other undesirable elements who had been sent to the northernmost province of SVN as a punishment. It was the fate of this division to receive the brunt of the NVA’s bloodiest offensive of both the Indochina and the Vietnam wars.

Under heavy pressure, the 3rd Division, outgunned and outnumbered, had to fall back, first to Dong Ha and then to the next line of defense south of the My Chanh River. This was defended by the Airborne Division (minus one brigade) and one Marine brigade.

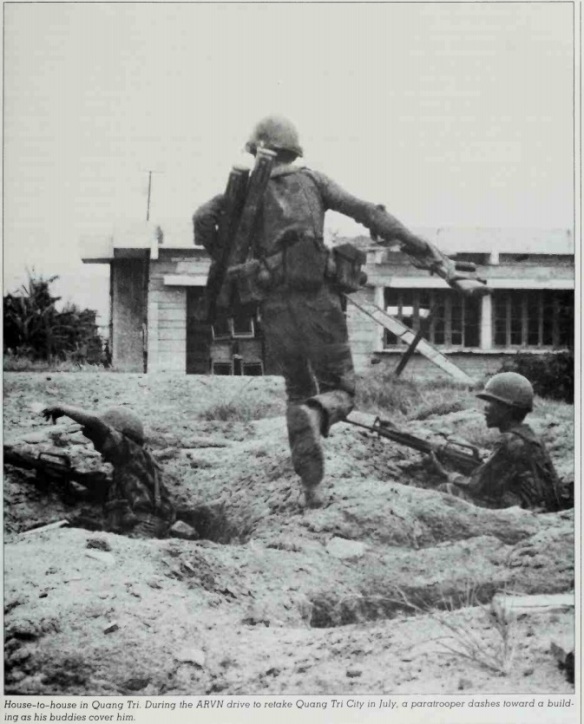

During the month of May, the situation was stabilized along the My Chanh River. NVA/VC troops had to stop to await resupply. The weather had improved, and tactical air support and B-52 sorties had taken a heavy toll. In early July, the Airborne and Marine divisions, refurbished and re-equipped, crossed the My Chanh River abreast, to launch the counterattack to recapture the city of Quang Tri. Although heavily outnumbered – by that time, the NVA’s order of battle consisted of the 304th, 308th, 312th, 320th, and 325th divisions – the Airborne on the west of RN1 and the Marine Division on the east, supported by US airpower, had caught the North Vietnamese off balance and quickly regained some strategic terrain north of My Chanh.

Differing from many actions earlier in the war, in 1972 the NVA chose to fight hard to retain their gains and resisted tenaciously. On the night of September 14, the 3rd Marine Battalion of the 147th Brigade blew a hole in the southeastern corner of the Quang Tri Citadel. During the night, the Marines fought block by block, and used hand grenades to destroy the last NVA/VC pockets of resistance. Finally, on September 15, after 48 days of uninterrupted fighting, the Vietnamese Marines, like their US counterparts in World War II on Iwo Jima, raised the national flag on the main headquarters of the Citadel and on its surrounding walls.

Concurrently with the offensive in Quang Tri, the NVA launched a powerful attack on Kontum province in MRII, using the NVA’s 2nd and 10th divisions as the main attacking force. Meanwhile, the 3rd Division made a diversionary attack in Binh Dinh coastal province. Brigadier General Ly Tong Ba, the ARVN’s 23rd Division commander, skillfully used his armored reserve task force to destroy the NVA’s attacking forces and evict them from the city of Kontum after hard-fought street combats.

While the “Tri-Thien” (Quang Tri-Thua Thien) theater was directly controlled by Hanoi’s High Command and the offensive in the Central Highlands by the commander of VC’s Military Region V, the attack on Loc Ninh and An Loc in MRIII was directed by nothing less than the Central Office of South Vietnam, Hanoi’s highest political organ in the South.

After the fall of the district town of Loc Ninh (20 kilometers north of the city of An Loc) on April 7, 1972, the ARVN’s Joint General Staff decided to defend An Loc at all costs. If An Loc fell, nothing could stop the NVA’s march into the capital of South Vietnam.

ARVN forces in An Loc originally consisted of the understrength 5th Division, the 3rd Ranger Group, and Binh Long provincial forces. They were later reinforced with the 1st Airborne Brigade and the 81st Airborne Commando Group. These two units were heliborne into an area approximately three kilometers southeast of An Loc, and had to fight off numerous NVA/VC attacks before linking up with the embattled garrison. Total strength of the troops defending An Loc was 6,350 men.

The NVA order of battle consisted of three divisions: the 5th, 7th, and the 9th. These divisions were supported by the 75th Artillery Division, with three artillery and one antiaircraft regiments. Additional combat support units consisted of three tank battalions. The attacking force totaled about 18,000 troops. The 5th and 9th divisions were to take part in the attack of An Loc, while the 7th Division was to destroy the ARVN’s reinforcement units trying to link up with the besieged garrison from the South.

The first attack on An Loc began on April 13. (In Paris that same day, Madame Nguyen Thi Binh, the chief of the VC delegation at the peace talks, declared that “within the next ten days, An Loc will be proclaimed the capital of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam.” The attack was launched by the 9th Division, supported by elements of a tank battalion. As usual, the assault was preceded by intense artillery preparation. The attacking forces quickly overran the Dong Long Hill and the airstrip located on the northern outskirts of the city, and forced the 8th Regiment and the 3rd Ranger Group to withdraw toward the center of the city. The NVA infantry, however, was stopped by AC-130s (transport aircraft equipped with fast-firing machine-guns) and helicopter gunships. Due to poor coordination between their armored and infantry units, NVA tanks continued to advance into the city without protection.

The first NVA tank was destroyed at the junction of Dinh Tien Hoang and Hung Vuong streets by three young members of the Self-Defense Forces. A PT-16 tank was set on fire in front of the underground bunker of Brigadier General Le Van Hung, 5th Division commander. A total of seven tanks were destroyed during the first attack.

On April 15, the NVA’s 9th Division renewed its attack on An Loc, with the 272nd Regiment in the north and the 271st Regiment in the west. Each of these attacking forces was supported by a tank company. Like the first attack, NVA tanks penetrated deeper into the ARVN’s positions without infantry protection. Five tanks were destroyed inside the city; the attack on the west was blunted before it began. As the 271st Regiment entered Xa Cat plantation, four kilometers west of An Loc, and began to deploy in formation for the final assault, the regiment headquarters and one battalion were hit by a direct B-52 strike. The attack on the western wing was cancelled entirely.

The NVA launched their biggest offensive on An Loc on May 11. The 5th Division conducted the main assault directed to the north and northeast, while the 9th Division attacked the west and south sectors of the garrison. The attack was preceded by an intensive artillery preparation, which lasted three hours.

Despite heavy air support, the situation had become critical by 10:00 am. In the northeast, the NVA reached a point only 500/m from the ARVN’s 5th Division Headquarters. In the west, elements of the 9th Division were stopped 300/m short of the 5th Division Headquarters.

At that time, General Hung ordered the 1st Airborne Brigade to counterattack to stop and destroy the two converging columns, which were dangerously closing in on his command post. The street combats raged all day long, and by nightfall the outcome of this seesaw battle remained uncertain.

The next day, the NVA tried to exploit their successes and widen their gaps by launching a new pincer attack, employing the 272nd Regiment of the 9th Division in the west and the 174th Regiment, 5th Division in the northeast. Both of these columns were supported by elements of a tank company.

With efficient tactical air support, the garrison held its ground and repulsed the NVA assaults. By nightfall, it became apparent that the offensive had lost its momentum and that, like the first two attacks, this one had also failed.

Toward the end of May, most of the North Vietnamese antiaircraft defense system had been destroyed by airpower. By early June, helicopters were able to land in An Loc for resupply and medevac. On June 9, the ARVN’s 21st Division, reinforced with the 15th Regiment, 9th Division, and supported by the 9th Armored Cavalry Regiment, finally linked up with the garrison of An Loc, after two months of uninterrupted murderous combat with the NVA’s 7th Division along Highway 13.

General Paul Vanuxem, a French veteran of the Indochina War, called An Loc the “Verdun of Vietnam.” Sir Robert Thompson, advisor to President Nixon, considered An Loc the biggest victory of the Free World in the post-World War II era. Douglas Pike described An Loc as “the single most important battle in the war.” Critics of the Vietnam War attributed the success of An Loc to US airpower. But General Abrams, the commander of US forces in Vietnam, had a ready answer: “I doubt the fabric of this thing could have been held together without US air,” he told his commanders, “but the thing that had to happen before that is the Vietnamese, some numbers of them, had to stand and fight. If they do not do that, ten times the air we’ve got wouldn’t have stopped them.” The South Vietnamese Army and its people did stand and fight.

In the furious battles of 1972, too often ignored by Western historiography, the ARVN showed what it was capable of when backed by US firepower and economic support.