Starting with the Anglo-German Naval Agreement (1935), which provided a legal veneer to Germany’s naval rebuilding program. Given mounting evidence that potential enemies were rearming at sea at an alarming rate, the government of Great Britain agreed in 1936 to the utterly false hope of rule-bound submarine warfare as enshrined in the London Submarine Agreement. In private, many in the Royal Navy assumed that Germany would quickly move to unrestricted submarine warfare at the outset of a new war.

While this planning failure reflected the historically offensive stance of the Royal Navy, it was not uniquely British. Similar overemphasis on capital warships and failure to appreciate the strategic role of submarines was evident in interwar planning and shipbuilding by other major navies, not least the Kriegsmarine and Imperial Japanese Navy.

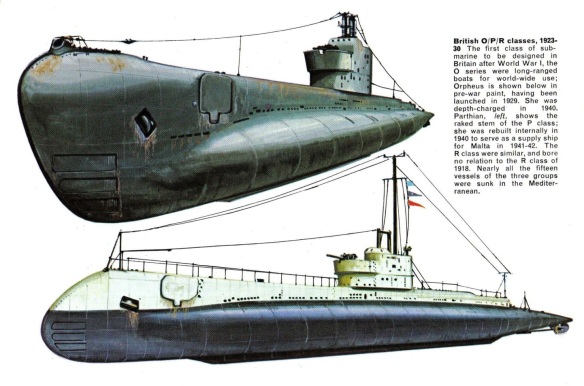

Like the Germans, the British began the war with a small number – 58 submarines, an inadequate number of boats. A resulting emergency building program to augment the fleet brought the wartime total to some 270 submarines. Max Horton, the successful submarine veteran of World War I, returned to service in January 1940 to command Britain’s submarines. Submarines from German-occupied countries also joined the British fleet after escaping from the Nazis; these included Polish, Dutch, Norwegian, Greek, Yugoslavian, and French boats including the famous Surcouf. While some of the French submarines joined the British, however, others remained at home and passed under Vichy control, and in this capacity were themselves sunk in combat by the British. The wartime British boats included some of the older prewar classes, including nine of the H-class, 18 of the O-, P-, and R-classes, and three of the L-class. However, the bulk of wartime British submarines were the workhorses of the fleet, the S-, T-, U-, and V-class boats. Design improvements in the later boats introduced welded construction, greater operating depths, increased endurance and range, and adding an additional tube aft so that the T-boats could fire three torpedoes from astern. Wartime building programs augmented the fleet; 50 S-class boats had been built or ordered by the end of the war, and 31 T-class boats, 46 U-class boats, and 21V-class boats were built between 1941 and 1945.

The growth of the British submarine fleet was partially offset by wartime losses. In all, 74 British submarines out of 206 that went to war were lost, along with 3,142 men. They fought in three major theaters; the North Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Pacific. The objective in the North Sea, especially off the Norwegian coast, was at first to try and blunt the German invasion of Norway, and then to interdict German shipping carrying iron ore and commodities to and from Norwegian ports. Submarines not deployed to attack ships and mine the coast patrolled Britain’s sea-lanes in the north to try and stop enemy ships and submarines from breaking out.

Not all submarines deployed in the war were large. The Germans and the Italians both developed “midget” submarines and small submersible attack craft during the war, among the more notable the German two-man 38ft 9in-long, 14.9-ton Seehund, which carried two 21in torpedoes, and the Italian Siluro a Lenta Corsa, better known by its nickname “Maiale” (pig), a two-man, 23ft-long human torpedo that ran on electric batteries, was steered and attached to an enemy ship, and detonated once the crew swam away. Following these German and Italian introductions of “midget” craft, Britain also developed small “midget” submarines – the Welman one-man submarine, the Chariot two-man torpedo-launcher, and the X-craft, a two-man, 51ft-long, 27 ton craft that carried two detachable explosive charges. The Chariots made an unsuccessful attack on the German battleship Tirpitz in October 1942, but in September 1943, two X-craft managed to damage Tirpitz badly in its supposedly impenetrable moorage in a Norwegian fjord.

The second theater was the Mediterranean, with an intense period of warfare between 1940 and 1943 when Italy entered the war and its naval forces controlled the central Mediterranean. The submarine war in the Mediterranean was a hard-fought campaign in difficult circumstances. Many areas were shallow, and the waters calm and relatively clear, leading to the detection and loss of a number of submarines. More than half of Britain’s wartime submarine losses, 45 boats in all, were in this theater. British submarines fought a particularly hard battle to interdict German and Italian ships resupplying the Afrika Korps in North Africa, and those based at Malta also had to contend, as did the island’s defenders, with a fierce series of assaults. In September 1941, the British sank 38 percent of the supplies headed to the Axis in Africa, and in the following month sank 63 percent of the tonnage. Every submarine that went to the Mediterranean to fight the Axis at that time was said to be “worth its weight in gold.”19 In all, the perseverance and bravery of the British submarine commanders and their crews resulted in the loss of over a million tons of shipping by the Axis – men, materiel, fuel, and ammunition – a feat that contributed to the ultimate Allied victory in North Africa. Britain awarded five Victoria Crosses to submariners – all of them for their role in the Mediterranean theater. One of the recipients, Lieutenant Commander Malcolm David Wanklyn, VC, DSO and Two Bars, had a particularly distinguished career while in command of HMS Upholder. He became the most successful British submarine commander of the war, sinking 120,000 tons over the course of 24 war patrols before Upholder and all hands were lost on her 25th war patrol in April 1942.

By war’s end, the British submarine force had performed an exceptional job, destroying 1,524,000 tons of enemy shipping – in all, 493 merchant ships and 169 warships were sunk by torpedoes and gunfire, and another 38 merchant ships were sunk by British submarine-laid mines. An amazing first in submarine warfare is also credited to a British submarine when the V-class submarine HMS Venturer, under the command of Lieutenant James “Jimmy” Launders, sank U-864 off the Norwegian coast on February 9, 1945. Tracking his enemy, Launders successfully plotted and fired a spread of four torpedoes to sink the U-boat; it was the first time in history one submarine had successfully attacked and killed another while submerged.

The vastness of the Pacific became the world’s largest submarine battlefield in World War II, as Japan and the United States faced each other in a deadly campaign that also involved America’s allies in the British Empire (the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada) and free forces from occupied countries such as the Netherlands. British, Australian, and free Dutch submarines operating out of bases at Trincomalee (Ceylon; now Sri Lanka), and Fremantle, Australia, in small numbers, worked the Straits of Malacca and the seas off Indonesia to interdict Japanese shipping throughout the war. After a complete withdrawal of all British submarines from the region by July 1940, only three T-class boats made intermittent sorties in the region until 1943, when the turning tide of war allowed Britain to send five additional submarines. At the same time, the Germans sent U-boats into the Indian Ocean to support Japanese sorties there, before moving on further into the Pacific.

Between September 1943 and August 1945, British submarines performed admirably, sinking a number of Japanese warships. By the end of 1944, they had accounted for a light cruiser, three submarines, six smaller naval vessels, and 40,000 tons of merchant shipping – and more than a hundred smaller junks, sampans, and other craft. British submarines secured the Straits of Malacca by March 1945, closing the door to the Japanese, and also successfully executed a Chariot assault on Phuket, sinking a ship there. Pushing into the Pacific in the aftermath of the US recapture of the Philippines, British boats scored an impressive kill by sinking the cruiser Ashigara on June 8, 1945, and made a successful X-craft assault on Singapore harbor on July 31, 1945. XE-3, commanded by Lieutenant Ian Fraser and crewed by diver James Magennis, successfully penetrated the shallow harbor, set six limpet mines on the cruiser Takao in an extremely difficult operation that came close to ending in disaster for the X-craft and its crew, and retreated as their charges sank Takao. Fraser and Magennis earned the Victoria Cross for this incredible and hard-earned feat. Their bravery underscored the small but important British submarine contribution in this theater, achieved with the loss of three submarines. The major undersea conflict in the region, however, was between the United States and Japan.

British Submarine Development

British submarine development was influenced by the cruiser and fleet submarine concepts. The main thrust of early evolution between the wars centered on the overseas patrol type, which displaced 1,475 tons on the surface and had a range of 10,900 miles at 8 knots, a submerged endurance of 36 hours at 2 knots, and a diving depth of 500 feet. Armament included a battery of 8 torpedo tubes with 14 torpedoes and a 4-inch deck gun. A group of similar-sized minelaying submarines also was built, as was a small series of very fast large submarines for work with the fleet, but both of these developments proved very expensive and of limited operational usefulness.

In the early 1930s, a fresh start was made with the Swordfish-class, which was designed for offensive patrols in narrow waters. These boats displaced 640 tons standard. They had a cruising range of 3,800 miles at 9 knots on the surface and 36 hours at 3 knots submerged, and they could dive to 300 feet. Armament was 6 torpedo tubes with 12 torpedoes and a 3-inch gun. A larger overseas patrol type, the Triton class, appeared in 1937. These displaced 1,090 tons standard; they had a cruising range of 4,500 miles at 11 knots on the surface and 55 hours at 3 knots submerged, and they could dive to 300 feet. Armament was 10 torpedo tubes with 16 torpedoes and a 4-inch gun. Britain concentrated its production of submarines during the war on these two types, producing a total of 62 of the S type and 53 of the T type.

Just before the war, the Royal Navy developed a small submarine for training not only crews and new commanding officers but also antisubmarine vessels. When war came, the design was quickly adapted for operational use, and the submarine proved particularly useful in confined waters such as the North Sea and Mediterranean. The U class displaced between 540 and 646 tons on the surface, with a range of 3,600 miles at 10 knots on the surface, a submerged endurance of 60 hours at 2 knots, and a diving depth of 200 feet. Armament included a battery of 6 torpedo tubes with 10 torpedoes and a 3-inch deck gun. A total of 71 boats were constructed of this class and its slightly improved successors of the V class. Although they were useful boats in the early part of the war, the later examples diverted resources from construction of more effective vessels. Britain also built some 36 midget submarines; with 4-man crews, these vessels attacked ships at anchor in harbor.