Having received training in tactical tracking operations, survival techniques, and living in a mock terrorist training camp during the “Dark Phase” portion of their selection course, Scouts would then be paired up with captured terrorists. These “tamed” terrorists would be given an AK-47 to help build trust between them and the Scouts. Sometimes the firing pin would be secretly removed until they had established a strong working relationship, just in case they were feeling froggy.

Phase 4: 1977–79

In late 1977, in the midst of Operation Dingo and fulfilling his promise to Vorster and Kissinger, Smith announced that he would negotiate with he African nationalists and accept majority rule. The upshot of those discussions was the political settlement of March 1978 and the formation of the interim government of Smith, Muzorewa, Sithole (who had been ousted from ZANU by Mugabe), and Chief Jeremiah Chirau to devise the new fully democratic constitution and prepare for the general election.

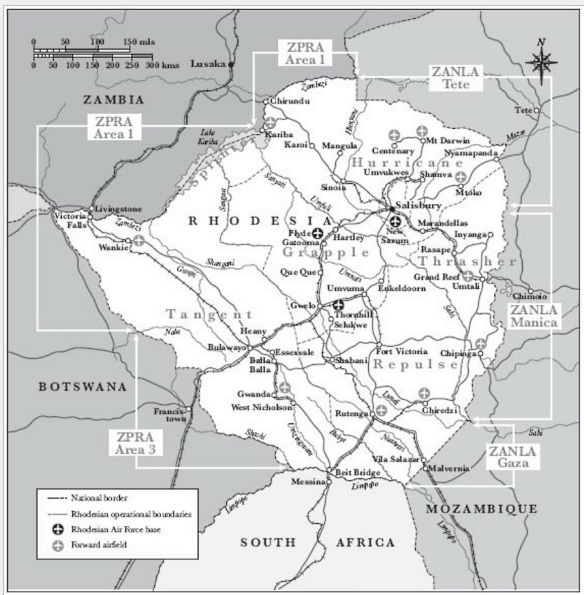

ZANU and ZAPU responded by unifying as the Patriotic Front, but their forces fought each other whenever they met. ZANLA intensified the war at great cost, with Fire Force taking a fearful toll. ZANLA also had severe logistical problems and lacked the morale, the discipline, and the training for positional warfare. ZPRA had conventional forces, but lacked a bridgehead across the Zambezi River and air support.

The increased fighting, combined with the prospect of being ruled by an African prime minister, shook the Rhodesian whites. Casualties remained light, but whites began to emigrate at the rate of 2,000 a month. Despite an infinite supply of eager African recruits, budgetary constraints and the shortage of training staff meant that the security forces could not expand fast enough to match the growth of ZANLA and ZPRA, and were soon outnumbered except at times of total mobilization.

Even so, the Rhodesian war effort improved and, with the prospect of success in the political field finally in sight, in 1978 ComOps produced a strategy with coherent goals which broke the reactive mold. This involved:

1. Protecting “Vital Asset Ground” (mines, factories, key farming areas, bridges, railways, fuel dumps, and the like).

2. Denying the insurgents the “Ground of Tactical Importance” (the African rural areas) as a base from which to mount attacks on crucial assets by:

i. Inserting large numbers of armed auxiliaries (loyal to Muzorewa and Sithole) into these areas to assist in the reestablishment of the civil administration and to destroy the links between the insurgents and their supporters;

ii. Using Fire Force and high-density troop operations against insurgent infested areas.

3. Preventing incursions through border control.

4. Raiding neighboring countries to disrupt ZANLA’s and ZPRA’s command and control; to destroy base facilities, ammunition, and food supplies; to harass reinforcements; and to hamper movement by aerial bombardment, mining, and ambushing of routes.

An addendum to this plan was CIO’s decision to sponsor the anti-FRELIMO resistance movement, Resistencia National Moçambique (RNM), which began to weaken FRELIMO and allow the Rhodesians greater freedom of action against ZANLA in Mozambique.

Although many in the Rhodesian security establishment did not grasp the potential of the auxiliary forces, the 10,000 auxiliaries, deployed among the rural Africans, began to deny the insurgents the countryside. For the first time, there were forces to occupy the ground which Fire Force won. Information began to flow again from the people, and Fire Force became more deadly. The operational demands, however, were excessive. Fire Forces deployed two and three times a day. Many external air and ground attacks were mounted, even on the outskirts of Lusaka in Zambia, but economic targets remained inviolate.

MID became more effective in the analysis of intelligence, and the army was strengthened by the formation of the Rhodesia Defence Regiment to supplement the Guard Force in guarding vital points.

Phase 5: April 1979–March 1980

The election of Muzorewa in April 1979 offered the only chance for the counterinsurgency war to be won because, voting in a 62 percent poll of the newly enfranchised African population, the moderate Africans dealt ZANLA and ZPRA a stunning defeat by defying their orders to abstain. The Rhodesian security forces mobilized 60,000 men to neutralize the threat to the election. During the three days of the election, 230 insurgents were killed, and 650 overall during the month of April. The others went to ground or surrendered. The ZANLA commanders left the country for orders and for six weeks the war stood still. If Margaret Thatcher had adhered to her election promise to recognize this internationally monitored result, the insurgency could have been defeated. Instead, Thatcher reneged and the murders of Africans increased as the insurgents strove to reestablish themselves. The morale of the security forces and the public sank. At the same time, planning to rob ZANLA of victory at a decisive moment, ZPRA deployed a 3,000-strong vanguard into Rhodesia to prepare the way for its Soviettrained, motorized, conventional army. ZANLA responded with an offensive into Matabeleland, ZPRA’s heartland. Although ZANLA deployed 10,000 men into Rhodesia, including some FRELIMO volunteers, it was in dire straits due to constant Fire Force action, the external raids, the unease of the host country, and the denial of ground by the auxiliaries. The peace achieved at the Lancaster House Conference in London came none too soon for ZANLA.13 Its real accomplishment was political. Its long campaign of intimidation ensured that Mugabe won the 1980 election.

Muzorewa could have achieved a stronger bargaining position if he had adopted a total strategy. Instead, while his security forces strove to contain the situation in expectation of a political solution, his political and military aims were not tied in closely enough. He could have exerted economic pressure and threat of a conventional war on Zambia and Mozambique to cease aiding his enemies. He could have stalled to allow time for his auxiliaries and Fire Force to weaken the hold of the insurgents within the country, while his forces crippled the supply lines of ZANLA and ZPRA and the RNM kept FRELIMO at bay. The humiliation of this could have caused the fall of the FRELIMO leader, Samora Machel. The Russians might have offered some help, but Machel had seen what had happened to Angola and would have hesitated to take it. The Cubans could have intervened, but this was unlikely as they were already overextended in Angola, and South Africa would have immediately reacted. There were political dangers, but Rhodesia had demonstrated that she could withstand international pressure.

Muzorewa could have enjoyed a number of options. A separate deal with Nkomo’s ZAPU would have been possible. The Lancaster House peace talks could have been stalled until the pressure on Zambia and Mozambique began to tell. Limited Western recognition might have been forthcoming to prevent a regional war. Muzorewa could have dictated the peace terms and his apparent strength would have appealed to the electorate because, like Mugabe, he could threaten the resumption of the war.

Muzorewa’s external operations did contain the ZPRA threat from Zambia, by blowing bridges and leaving Zambia totally dependent on a single railway line through Rhodesia to South Africa. The raids steadily raised the odds in Mozambique to force FRELIMO to cease supporting ZANU and ZANLA. The Rhodesian forces attacked bridges in the Gaza Province to cut ZANLA’s supply lines. They planned to do likewise in the Manica, Sofala, and Tete Provinces had they not been stopped. Perhaps they were stopped because the British were bent on achieving a settlement embracing all players, including Mugabe, and the South Africans wanted to woo Machel to deny their ANC safe havens. Muzorewa also weakly allowed the British to divide his delegation, while Mugabe and Nkomo delayed signing anything to gain time to build their political support within Rhodesia and recoup their losses.

Enforcing the ceasefire, the Commonwealth Monitoring Force restrained the Rhodesian forces and ostensibly confined the ZANLA and ZPRA forces to a number of assembly point camps. The British, however, ignored the presence of mostly recruits in the camps and the absence of the hard core, who remained outside among the population and ensured that Mugabe won the election. The British, with too few troops to intervene, accepted the result despite the overwhelming evidence of intimidation.

The Rhodesian forces flirted with, but rejected, the idea of a coup because only Britain could confer sovereignty. Instead they concentrated on forcing the British to reschedule the election. Lord Carrington, the British Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary, aided and abetted by Ken Flower, the Head of CIO, and P. K. Allum, the Police Commissioner, ignored the evidence of widespread intimidation supplied not only by the Rhodesian forces but also by the British monitors.

In the end, the leaders of the intelligence establishment betrayed their own, perhaps for the sake of their pensions. Flower went on to serve Mugabe and his Marxist aspirations, and the CIO became a feared secret police organization rather than an intelligence agency. The war cost ZANLA and ZRPA 40,000 dead at a cost of 1,735 Rhodesian dead – a ratio of 23:1. A flawed election placed Mugabe in power and, bent on the retention of power, he has ruined a once thriving state. Where once food was exported and policemen went unarmed, famine and terror stalk the land. All the Rhodesian military gained out of the failure of the counterinsurgency campaign was an enviable reputation.